The rules around ownership can be a legal maze – here’s what HNWs need to know, writes Sophie Wettern

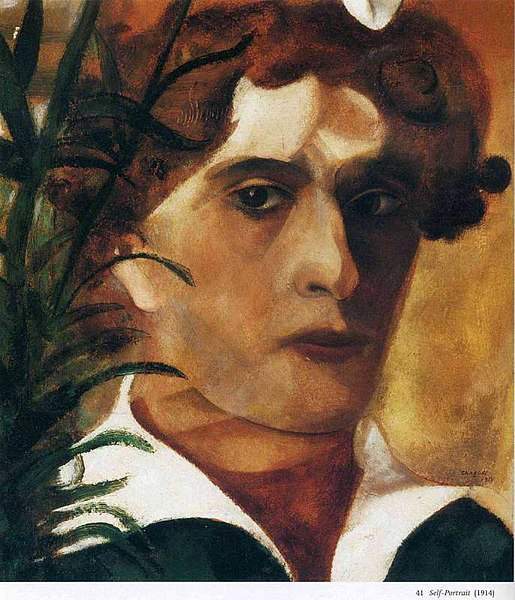

Anyone following the art world will have seen the recent drama surrounding Marc Chagall’s ‘Wallflowers’ which was purportedly bought by three art dealers from a New York dealer – who later turned out not to own the painting at all. The artwork is currently subject to an ownership dispute between the purchasers, who state that they bought the painting in good faith, and a US collector who bought it for $1.2 million in 2015. The US collector had delivered the painting to the New York dealer with the intention to sell it at some point in the future. He is claiming that the sale was not legitimate, as the painting was subject to an outstanding loan, and that the three purchasers failed to carry out sufficient due diligence.

This is one example of a category of dispute where an asset is transferred but the ownership position is not entirely clear. Under English law, there are various ways in which ‘real ownership’ may be unclear and disputes may unfold.

A key point to be aware of is the distinction between legal and equitable title under English law. One reason why this may be relevant is that minors cannot hold real estate in their own names. The legal title to the property will be held by an adult, perhaps a parent or other relative, and the beneficial interest, or ‘equitable title’, will be held for the benefit of the child. This construct is known as a ‘bare trust’. Where land is held on bare trust, this will be reflected by a restriction on the title of the property at the Land Registry. However, bare trusts can also be relevant in other contexts, for example a parent might open an investment account for the benefit of their child. Equally, a nominee may hold an asset on bare trust for an undisclosed third party.

So what happens when you purchase an item which is then subject to an ownership dispute, like the Chagall painting? Generally, purchasers are subject to the maxim of ‘caveat emptor’ or ‘buyer beware’. The obligation is usually on the purchaser to ascertain what exactly they are buying, including any restrictions or flaws in the legal or equitable title.

In the context of real estate, however, an innocent purchaser who purchases in good faith for value, without notice of any other party’s claim against the property, will be protected. So long as the bona fide purchaser properly records the transaction, they will take good title to the property. Those parties holding competing adverse claims may bring an action only against the fraudulent transferor.

However, there is also a property law concept of ‘proprietary estoppel’ which is relevant where an individual has been promised certain future rights. This is often relevant in a family context, for example where an adult child works for a low salary in the family business on the understanding that they will inherit in due course. There are three key elements to establish proprietary estoppel. There must be a promise or assurance to the individual which gives rise to their expectation that they will have a proprietary interest, for example, an adult child is promised that on their parent’s retirement, they will inherit the family business. The individual must have relied on that expectation to their detriment, e.g. they continued to work for the family business on low pay, on the understanding that they would in due course inherit the business.

The key moral of the story? Make sure you are clear about current ownership when purchasing assets and don’t make any impromptu promises.

Photo credit: Wikimedia Commons

Sophie Wettern is an associate at boutique private wealth law firm Maurice Turnor Gardner LLP