Christopher Jackson heads to New York for the $800 million sale of the art collection of Peggy and David Rockefeller – and finds it indicative of a changing America

As you drive down Sixth Avenue towards Christie’s New York, you pass a sequence of names too famous to require explanation: Apple, Massimo Dutti, Salvatore Ferragamo. Then suddenly – with a near spooky inevitability – the word ‘TRUMP’ looms up at you: the Tower. But there’s another name you see wherever you go in New York: that’s Rockefeller, of course, and it summons quite different associations from the president’s. Synonymous with taste, style, philanthropy and fabulous wealth, age cannot wither it.

I am in town for the sale at Christie’s of the art collection of Peggy and David Rockefeller. David, who died in 2017 at the age of 101, was the last surviving grandson of John D Rockefeller, the philanthropic founder of Standard Oil. David entered the Chase Manhattan bank as an assistant manager in 1946; at the time of his death his estimated worth was $3.3 billion.

All the while, David and his wife Peggy – who died in 1996 – were practising a hereditary Rockefeller trait: the indulging of superb taste. Upon David’s death, Sotheby’s and Christie’s jostled for the right to conduct the sale. Christie’s won – apparently because it guaranteed the estate a minimum total price of $650 million.

During his lifetime, the collection was spread across David’s various houses – including a seven-floor townhouse in Manhattan and Kykuit, the family’s mansion overlooking the Hudson river, 25 miles away on the Pocantico Estate. It is an almost intimidating collection: in addition to masterpieces such as Picasso’s Fillette à la corbeille fleurie (1905), Gauguin’s La Vague (1888) and Seurat’s La Rade de Grandcamp (1877), there is every kind of porcelain. But among the great European works, another story emerges: a tale – very unTrumpian, you might say – of internationalism.

Take, for instance, lot number 953, a Korean fluted vase – a thing of lovely elegance, like milk frozen in the act of being poured. My ambition to own it is stymied by the estimate: $4,000-6,000.

There’s also a range of Buddhas and bodhisattvas which reflect the Rockefellers’ global outlook. Margaret Gristina, from Christie’s New York Chinese art department, explains this side of the collection: ‘David collected Chinese porcelain from the Kang Xi period and he was crazy about them. His mother had a Chinese Buddha room in the house in Maine. They have a wonderful common thread of beauty through everything.’

That ‘common thread of beauty’ is evident throughout the collection. Jonathan Rendell, the deputy chairman of Christie’s US, notes lot 996 – an Ayyubid incense burner, made in Syria in the 13th century. ‘It’s a unique object in that it has both Muslim and Christian decoration on it,’ he says. ‘This was the object that sat on Mr Rockefeller’s desk all the way through his career: it was bought by his parents in the Twenties, and it’s in all the photos of him at Chase, and towards the end of his life. It was always beside him.’

The estimate? $150,000-200,000. When I ask Rendell whether it’s his favourite piece is in the collection, he chuckles and says: ‘Never get fond of anything: there’s too much stuff.’

One person who had particular reason to get attached is the Rockefeller family historian Peter Johnson. Plucked from academia as a young academic, he has since dedicated his life to the family, working as both a historian and right-hand man for David. ‘I ended up being integrated – taking trips with David, helping to write speeches,’ Johnson tells me as we move through the sale. ‘The wonderful thing about David is that you never felt like you were working for him. He always said when he introduced me, “This is Peter Johnson, he’s working with me.”’

Rockefeller also exhibited a marked ‘unpretentiousness’ with objects, says Johnson. ‘The things that he had closest to him were the things he had most affection for. He had this wonderful little Tang rice bowl and he used that for paperclips. There was another Chinese bowl which had somehow migrated up to the house in Maine. The story is they used it to feed the dog. They weren’t disrespectful, but it was part of their lives.’

I ask Johnson if he has any particular favourites. He gestures towards Gauguin’s La Vague. ‘This Gauguin is a particularly good one. My wife had gone to [the Rockefellers’] homes a couple of times. She said afterwards, “I feel liberated when you look at what Peggy and David did in their homes: you realise you can put anything together with anything.” The Gauguin hung in the library in David’s townhouse. There was a Persian rug too, and 18th-century English furniture. They somehow fit together.’

For Johnson, the binding force was David’s personality: it is, he says, ‘mystical’ how the objects were held together by the personality of their owner. Having spent a pleasant afternoon the previous day in the Frick Collection, I ask Johnson if he feels an opportunity has been missed to create a museum in that great tradition: ‘He [Rockefeller] never really considered it,’ he says. ‘I think he felt it would have been somewhat immodest to say, “I’ve got such great stuff that I can charge people to look at it.”’

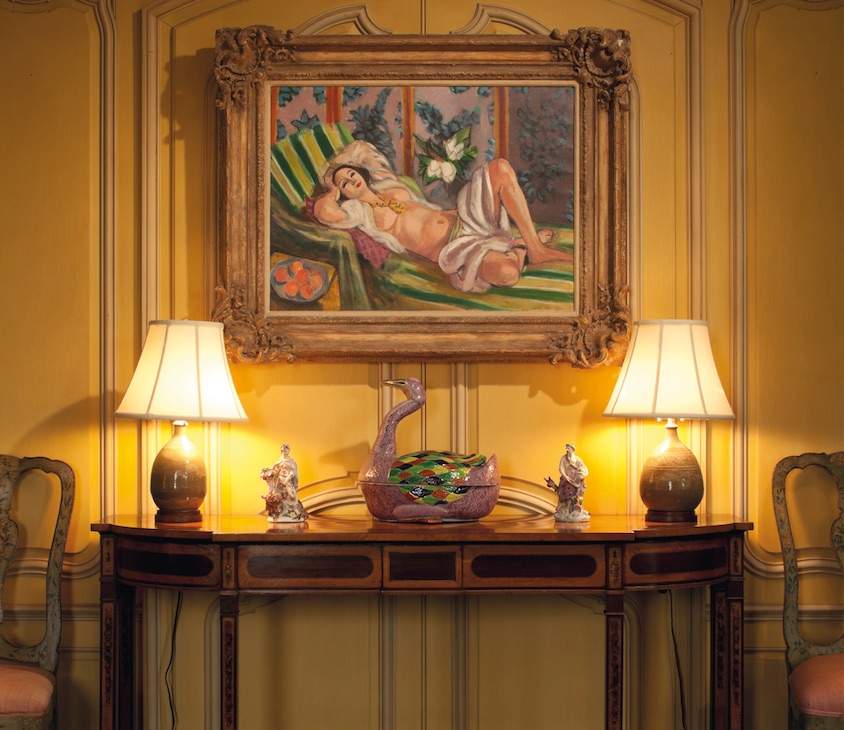

In the downstairs rooms are the early star lots: Matisse’s Odalisque couchée aux magnolias (1923); Seurat’s superb La rade de Grandcamp (1885); that marvellous Gauguin; the small matter of the most represented artist in the sale, in the shape of five Monets; and the exquisite Picasso, Fillette à la corbeille fleurie. I become interested in that Picasso – a rare rose period picture of a young girl holding flowers, which was painted in October or November 1905. This was owned by the Steins, eventually being bought in 1968 by a syndicate set up by David Rockefeller: when the Rockefellers drew lot number one from a hat, they plumped with expert taste for this picture.

Looking at this figure – her vulnerability, and even her defiance – I realise that we are standing on the cusp of a great dispersal. One wants to capture these in the mind until they vanish for ever. The slight dash of rose on the girl’s heel; the indistinct fluster of her hair; and the Rothko-ish background – the blueish infinity in which she stands. In John Richardson’s great book on Picasso this girl is in very poor black and white; here she is now in all her vulnerability and poetry. But where will she be in six weeks’ time? And where will Monet’s forensic water-lilies, all nuanced light and tacit growth, be this time next year?

And so on to the sale. Conor Jordan, a specialist in Impressionist and Modern art at Christie’s, describes his emotions: ‘The adrenalin is extraordinary: there are a million things to do, a million people calling you and wanting to talk about things. And a lot of important decisions have to be made: everything’s coming thick and fast.’

The early lots cause astonishment: Picasso’s Pomme (1914) realises $3,972,500 after a contest between nine bidders; there’s a new world record for Delacroix when Tigre jouant avec une tortue (1862) sells for $9,875,000. The Odalisque sets a new record for Matisse. Nymphéas en fleur (c 1914-17) becomes the most expensive by Monet in history, at $84,687,500. Meanwhile, my Korean vase goes for an extraordinary $68,750; Rendell’s incense burner for a dizzying $432,500.

In the end the collection fetches $832 million: a triumph – and yet there is an undeniable melancholy in the air too, which has to do with mortality, and the passage of time.

So what does the collection say about America? For the Rockefeller archivist, this is a fin de siècle moment. ‘It happens in history,’ says Johnson with a historian’s relish. ‘By purchase or conquest all sorts of things ended up in the great museums of Europe. It’s an indicator of power – and when they begin to be dispersed, it shows that a zenith has been reached: we know that 40 per cent of the art market now is Chinese. Twenty-five years ago it was zero.’

Power – it is never far away from any discussion about the Rockefellers. Johnson tells me about all the people who came to the townhouse down the years and would have seen the collection. One by one, he summons them: Henry Kissinger (‘he appreciated the art but was never much of a collector’); the King of Morocco (‘you’re never sure how to behave: there’s this guy next to him with a sword that could cut off your head’); Anwar Sadat (‘David and he really were friends’); and Ted Heath, with whom Peggy had a particular rapport, as they were both pianists.

It’s like a who’s who of the 20th century: there’s Fidel Castro (‘it’s funny when you’re looking at someone who’s really a world historical figure, he’s dressed in these old fatigues and a beard’); Bill Clinton (‘he had that glow of power, and then when he left the presidency it was like he’d lost his lighting team’); and George HW Bush (‘he didn’t care that much for the art. He assumed that this was how a Rockefeller lived’).

The internationalism of the Rockefellers, patriots though they were, keeps returning, too. Of King Hussein of Jordan, Johnson recalls: ‘David would say, “My mother bought this rug in Damascus in 1924.” It was his way of showing his international side.’

As we part ways, Johnson says: ‘The ruling houses, the church or the governmental entity used to maintain the place where these things existed. Now everything has become monetised, so that the intangible value of art becomes an asset class. As soon as Adam Smith began writing, this became inevitable.’

The next day, I head for 146 East 65th Street, David Rockefeller’s townhouse. Sold at a steal for $20 million last year ($12.5 million less than the asking price), it’s a short walk from Central Park. Here, in the thrust of Manhattan, even privilege must be discreet about itself. True, the Roosevelts lived on 65th when FDR was governor of New York, but otherwise it looks like a typical Manhattan street – the restaurants with their outlandish portions and indifferent coffee; the suspicion of surrounding height;

and the indefinable imperialism of America told in the indignant bonhomie with which they respond to requests for directions.

I find the house uninhabited. Through the windows, I glimpse dust sheets and bare surfaces: death’s essential humourlessness and lack of manners. The Rockefellers will go on, of course, from David Jr to David Jr, and the pictures will migrate from time to time into public museums. And more philanthropy will flow from the sale. Afterwards, David Rockefeller Jr, the chairman of Rockefeller & Co, tells Spear’s: ‘It was always understood among my siblings that the family properties and collection would be destined for sale in order to continue supporting the family’s commitment to the philanthropies with which they were most closely involved.’

And David Jr’s favourite picture? ‘The Matisse Odalisque. For years it hung in my father’s country house and it was strategically placed so that from his favourite chair by the window – where each morning he consumed the newspaper and a first cup of coffee – he directly faced the Matisse.’

This brings us full circle. At the sale, the winning bids for the record Matisse and the record Monet were both taken by Xin Li Cohen, the deputy chairman of Christie’s Asia, indicating that they came from Asia. I’m not sure that John D Rockefeller (who opened the first medical school in China) or David Rockefeller would particularly mind that.

As I walk away from the empty house, I find myself thinking again about the current president. It suddenly occurs to me that I forgot to ask Peter Johnson about Donald Trump – a New Yorker after all. That evening, I write him an email to ask if the two ever met. A few hours later I get a one-line response: ‘Mr Trump was never invited to any of the Rockefeller homes.’ That seems to say a lot.

The Christie’s sale of The Collection of Peggy and David Rockefeller was partnered by the first and only global aviation company, VistaJet, to enrich the exhibitions and tour in

Hong Kong, London, Paris, Beijing, Los Angeles, Shanghai and New York. ‘The fact that 100 per cent of the proceeds from

the auction of the collection are to be donated to charities worldwide is a remarkable philanthropic effort,’ says Nina Flohr of VistaJet. ‘We are very proud to have supported their initiative as the key global partner.’

Web vistajet.com

Christopher Jackson is deputy editor of Spear’s

Related Stories

Thomas Cole, National Gallery – from Eden to Empire

Monet and Architecture, National Gallery review