As the niece of Winston Churchill and the widow of Anthony Eden, the Countess of Avon is a fascinating link to both the glories and the darkest hours of the past, writes Alec Marsh

‘Have a cocktail,’ suggests the Countess of Avon, in an imperious tone that sounds like an instruction. The 97-year-old niece of Winston Churchill and widow of postwar prime minister Anthony Eden is lowering herself into a chair. We’re in the elegant drawing room of her Bryanston Square home in Marylebone; the intended topic of conversation is her uncle, currently being celebrated in art and popular culture as never before. Three tall windows overlook the square, and the sage-green walls of what she calls a ‘salon’ are coated with beautiful artworks, including one painting by the French cubist Marie Laurencin that catches my eye. ‘It’s a painting that my husband liked,’ Lady Avon explains. ‘He had a very good eye. He was always buying paintings.’ Was that something he had in common with Churchill? ‘My uncle didn’t have a good eye,’ she chuckles genially. ‘He did painting; they were quite nice. But he wasn’t an aesthete, but my husband certainly was.’ We settle on coffee.

Born Clarissa Spencer-Churchill in 1920, Clarissa Eden – as she was known after she married in 1952 – is the daughter of Jack Churchill, the younger soldier brother of Winston, and Lady Gwendoline Bertie, daughter of the Earl of Abingdon. As well as being the niece of a prime minister and married to one, her lineage includes her grandfather Lord Randolph Churchill, who was chancellor of the exchequer in the 1880s.

But this was all a long time ago: indeed, her own experience of public life – which she says she did ‘not particularly’ enjoy – as the wife of Churchill’s long-time lieutenant andeventual successor in Downing Street terminated 61 years ago. That’s before the Beatles had formed, before the Manchester Guardian had moved to London, before Hitchcock made Rear Window; it’s 11 prime ministers ago. So it’s not surprising that Lady Avon’s memory is not quite as clear as it once was. But she is happy to answer as best as she can.

Like millions of others, she has seen Darkest Hour and was enthralled by it – including Gary Oldman’s portrayal of her uncle. Would Churchill, I ask, be surprised by the public adoration being heaped upon him today, more than seven decades after the moment of his greatest triumph? ‘I don’t think so,’ she says shrewdly, ‘because by the end of his life he was very great, wasn’t he? It would be very difficult not to realise that he would be remembered.’ Would he be pleased about it? ‘Yes he would, of course.’ She smiles. ‘Naturally.’

We all think we know something of her uncle, but how does she describe him? ‘That’s very tricky,’ she starts, ‘because I always knew him as a great man who hadn’t been appreciated. Most of my [early] life he was a failure. He was out of a job, out of work and not right in anything he believed in. He was in exile, so to speak. Going to Chartwell [the Churchills’ home in Kent] before the war was going to a place in exile – a place where people were not doing anything. It was all rather frustrating and sad.’

That all changed in May 1940, when Churchill became prime minister. The future Lady Avon was just 19, and just two years after she had ‘come out’, as one of the notable debutantes of her year presented at court with Deborah Mitford, later Duchess of Devonshire. That followed several years in Paris and Oxford, where she befriended Evelyn Waugh – ‘a good writer… But that was my world before I was married. I don’t think I ever saw him afterwards’ – Isaiah Berlin, Anthony Powell, Greta Garbo and many others.

During the war, Avon worked at the Foreign Office in what she says was ‘not an exalted position’, decoding documents. ‘I didn’t think that because I was in the Foreign Office I had a lot of advantages,’ she recalls. ‘My advantage was that I was Winston’s niece and saw him quite often.’

There was a price, though. ‘Sometimes one was attacked because Winston was one’s uncle,’ she recalls, adding philosophically: ‘Part of the political life.’ She pauses, thinking. ‘Yes, people were very rude to one certainly, because he was one’s uncle. No question.’ How did she respond – did she give as good as she got? ‘Yes, but not too much because that’s a mistake if you get into terrific trouble all the time. I had Randolph as an example of not giving as good as you get.’

The negative comments did not, ofcourse, stop her from making frequent visits to her uncle in Downing Street during the war. So what did she find? ‘There was always a crisis, a tension, but one knew that that’s what he lived on; the fuel that got him going. Which it did with any good politician,’ she adds, noting that the same was true for her husband. Did Churchill wear the pressure with equanimity? ‘Oh yes. Of course,’ she insists, as though nothing else would be possible. ‘Certainly.’ How did he cope? ‘I don’t know. But he had always done it.’ Did he drink too much? ‘No, not more than most men,’ she fires back.

I ask about her wartime visits to Chartwell: ‘I didn’t particularly like it, but it was interesting always because Winston was so interesting,’ she recalls. ‘One always wanted to know what he was thinking and doing.’ Whatever the house itself lacked in aesthetic quality (‘Have you ever seen it?’ she asks), its host more than made up for its architectural shortcomings. ‘It was just him,’ Avon states emphatically. ‘One went and there was him and nothing else. They had the lunch or whatever it was, and he would talk and one would listen; that was the important part.

‘But he was not interested in what anybody else had to say,’ Avon recalls, laughing fondly. That said, she insists that he was ‘very polite’. ‘If somebody famous was at lunch he would listen to them, but on the whole he didn’t pay any attention to anybody.’

Was he entertaining company, I ask; funny? ‘He was certainly witty…’ And somewhat terrifying at times? ‘Not in the least, no. But,’ she breaks into laughter, ‘I could see he was terrifying, but not to me, no.’ Avon also recalls that he was ‘very conscious about things like nieces and nephews’.

All these years on, how does she remember him? ‘He was exceptional, certainly,’ she punctuates this with a frank chuckle. ‘I think I realised he was very great in spite of the fact that everyone kept telling one that he was.’ She raises her eyebrows. ‘I did realise that he was exceptional. You couldn’t not.’ The greatest prime minister of the twentieth century? ‘Who was greater?’ she answers.

What does she think Winston would make of modern Britain? Lady Avon looks over towards the tall windows momentarily. ‘Not much,’ she chirps. ‘I don’t know. He was very, very old-fashioned in his approach to life.’ That comment sits a moment; the quiet of the square seeps into the salon.

Where would Churchill be on Brexit, I ask? ‘I think he would probably not [be] very much for staying in Europe,’ she announces after some consideration. ‘But he was a good politician,’ she adds, ‘so I don’t know what he would have said.’ Which is rather a good answer when you think about it.

The curse of Suez

I turn to the subject of her husband, who was 23 years her senior and died in 1977. It was, of course, his long-anticipated but short-lived premiership from 1955-57 that led Britain into the national humiliation of Suez in 1956. I wonder how he saw it all; was he proud of his career?

‘I suppose so,’ she replies doubtfully. ‘Absolutely.’ Does she think people have the wrong sense of Suez – that it was a mistake? There’s a long pause. ‘A mistake because it took place at all?’ she asks. ‘I don’t know,’ she states at last. (At the time she famously said that she ‘felt as if the Suez Canal was flowing through my drawing room’.) I wonder if memories of this crisis have fallen prey to time, as she explains: ‘I’m not good at politics, I’m afraid.’ I’m still not sure as the silence of Bryanston Square returns.

How would Eden have liked to be remembered? ‘You mean as a success or failure?’ she responds. ‘Certainly [he] was a success at the beginning,’ she says, referring to his three spells as foreign secretary – covering ten years between 1935 and 1955 – before the disappointing period of highest office. ‘At the end, I suppose not. I never thought about it,’ she adds absently. She reaches forward to the plate and nudges a biscuit towards me. ‘Have that one,’ she says.

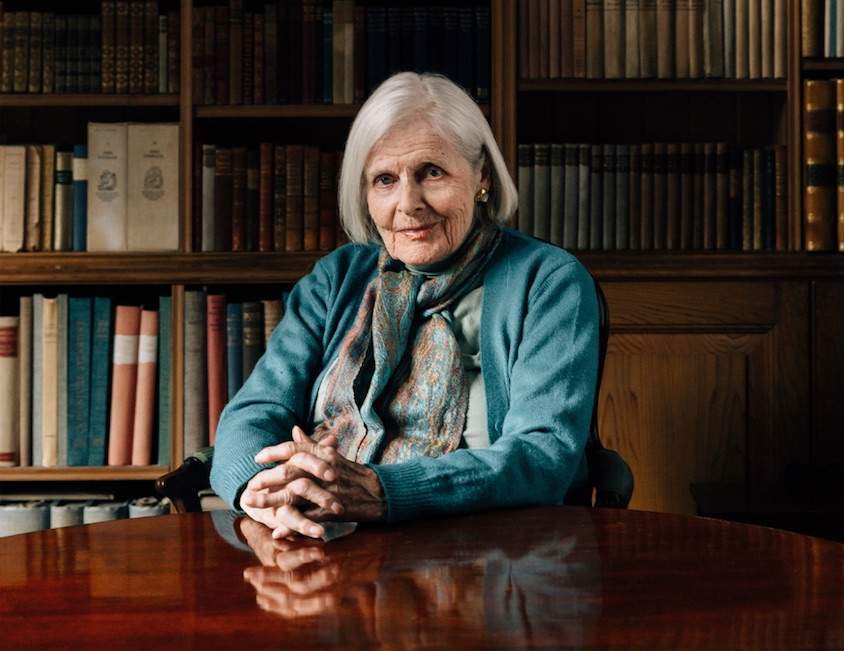

We go through to the library, where photographer Greg Funnell and his assistant Linda have prepared the room. As Lady Avon poses for pictures (‘Smiling is not my thing,’ she states with a chuckle), the conversation turns to photography. Funnell asks if she knew of Yousuf Karsh, who took a famous portrait of Churchill, hand on hip, at the Canadian parliament. She did not. I mention Cecil Beaton, whom Avon did know. ‘He never took a good photograph of me,’ she declares.

More pictures are taken. ‘I am very impressed with how little light you want,’ remarks the subject. I spot three volumes of Eden’s memoirs on the shelf; nearby is a copy of Seven Pillars of Wisdom. Opposite is a shelf dedicated to Churchill, including six volumes of The World Crisis, his story of the Second World War, and his four-volume book A History of the English-Speaking Peoples. I wonder who has turned the pages of these books, whose eyes read the print and what thoughts they inspired.

‘What does your tie represent?’ asks Lady Avon, looking over. It’s decorative, I say. ‘That’s disappointing. Right,’ she chirps, addressing Greg. ‘Where am I looking?’

Alec Marsh is editor of Spear’s

Photography by Greg Funnell

Related articles

Interview: Yanis Varoufakis on the end of Europe – and capitalism

Spear’s interview: Norman Lamont, the prophet of Brexit