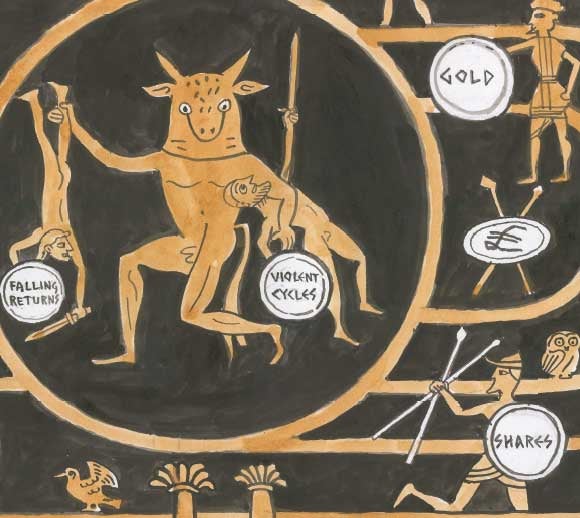

What’s the intelligent thing to do with your money in 2017? Christopher Jackson enters the wealth labyrinth to find out

Money is a labyrinth. Wealth managers live by their ability to discern the thread that can lead the UHNW away from whatever Minotaurs of inflated prices may lurk, towards an airy world of smart investment. But nowadays – arguably like never before – there is no sure bet: the variety and unpredictability of the world can alter at any time an apparently sound investment.

Happily, Spear’s is on hand. When we conducted our annual survey into the wealth management industry, we asked those we interviewed where the smart money is going in 2017. Those who shared their ideas emphasised the importance of deciding one’s attitude to risk: many wealth managers operate precisely by spreading hazard. The phrase ‘balanced portfolio’ is not one seldom heard in the industry. But what if you’re willing to set aside a part of your portfolio to shoot for double-digit returns? The answer you’ll hear most often is private equity (PE). Although there are still claims made in academic circles that PE’s reputation for exceptional returns is inflated, the wealth managers Spear’s met remain optimistic about this asset class.

First of all, PE has grown partly as a result of the decreased attractiveness of other asset classes. As Peter Thompson of St James’s Place told us: ‘In the UK, pension planning has been hit, limiting the opportunity for significant planning, and so we’re looking at VCTs [venture capital trusts] and EISs [enterprise investment schemes] – a lot of money that in the past would have been funnelled into pensions is going there.’ That’s a shift caused by restrictions to the annual pensions allowance, and also reflects a change in society. We used to save for a comfortable but perhaps staid retirement – now even retirees prefer to take their chances with jazzier investments.

Secondly, there are also clear benefits to investing in a company over other asset classes, such as real estate. A company is more flexible: it can react nimbly to contingency, and this can be valuable in the post-Lehman world – doubly so if you can pick the right company with savvy directors.

Thirdly, a long-running, nearly surreal, bull market has led some to fear that equities are looking overvalued, which has in turn contributed to PE’s attractiveness.

Lastly, and perhaps most importantly, there is its sheer pace of change, as PE veers away from its staple debt-fuelled buyouts towards more sophisticated structures. It can now embrace all asset categories – from credit to real asset – and it’s also possible to co-invest, directly invest or proceed with separate account structures. PE is nothing if not dynamic.

Nevertheless, Charles Sanford, an investment adviser at Credit Suisse, emphasises the importance of interweaving safe aspects into portfolios: ‘Smart money is going into defensive structures which give equity upside but take advantage of selling volatility to protect on the downside,’ he explains. ‘It’s possible to generate a 7-8 per cent pa return and also protect your capital even if capital is down.’ Observations like this remind us that we still inhabit the aftermath of the 2008-09 financial crisis: people have not found it easy to forget the tail-end of the Bush administration.

Nor perhaps should they. But as the years have gone by, PE has become a staggering growth area. Some analysts think it will increase from its current $4.3 trillion AuM to $15 trillion over the next ten years. It can be bewildering to know where to start. Should one focus on Europe and the US, or angle for something more adventurous? If the latter, it particularly helps to think geopolitically. Each private equity fund has its relationship to the prevailing political situation. Many wealth managers today see Brexit and Trump as temporary setbacks in an age of unstoppable globalisation: accordingly, many are still looking overseas.

The enormous potential of China is attractive, if only it can be satisfactorily tapped. William Drake, co-founder of Owl Private Office, regularly visits the jurisdiction and the trick, he insists, is to get out of Beijing and Shanghai and understand middle China: ‘The middle class and lower middle class in China is getting steadily wealthier,’ he explains, ‘and they’re buying fast-moving consumer goods which we take for granted – pineapple juice, babyware, nappies, toothpaste, all these things. But the Chinese stock market is gambler-oriented, and there’s no institutional core to keep it steady: it’s volatile, with very difficult corporate governance.’

As a result, only sophisticated investors can tap the Chinese market. Daniel Pinto, CEO of Stanhope Capital, elaborates on the difficulty with China: ‘There are fantastic companies there, but as a minority investor you should not expect accounts audited by PwC and you won’t get a board comprised of independent investors. It will often be a family at the helm, and their notion of good corporate governance is not ours.’

Those difficulties have many looking elsewhere. India, for instance, has a similar dynamism to China but it lacks its drawbacks. Pinto explains: ‘Where the Chinese economy is still very reliant on exports and on public investment, India is largely driven by domestic consumption. That’s a strength, and makes the country less vulnerable to cycles.’

And what if your risk appetite is not yet sated? In respect of the other BRIC countries, the consensus is that it’s too early to bank on Brazil: it lacks strong political leadership and remains heavily reliant on commodities cycles, and these can easily turn violent. Russia is still very much for the brave, although Pinto is among those who see some ‘very interesting companies’ there, if you can see past the idiosyncrasies of the Putin regime. On the other hand, it’s also important not to get carried away. ‘When you look at the performance [in these jurisdictions],’ explains Pinto, ‘private equity funds investing in these regions have not performed as well as US or European funds. But the promise is there.’

A similar warning comes from Alan and Gina Miller of SCM Direct. ‘If you look at the relationship between GDP growth and stock market performance there’s very little correlation,’ cautions Alan Miller.

And what if the BRIC promise never materialises? Furthermore, what if the world is changing in ways that people aren’t yet even prepared to contemplate? One who thinks we are on the cusp of a shift towards a more protectionist environment is Jonathan Ruffer, the City grandee, founder of Ruffer & Co, and self-described market pathologist. Ruffer views history as a series of cycles and argues that an era of internationalism is passing: for him, we are entering a new cycle where the smart money isn’t quite where you think it is.

‘I think of it [Brexit] as a farmer in a field of bullocks. Brexit is an outbreak of bullockry,’ he tells Spear’s. ‘It signals that internationalism is coming to an end… My conclusion is that eventually those who lose in a deeply deflationary world will become discontented, and that will become disruptive.’ That sounds almost apocalyptic, but Ruffer also argues that good could come out of even such considerable change. ‘Balkanisation is always bad for profits but it brings societies back to life again,’ he says.

For Ruffer, moments such as the presidential win by Emmanuel Macron in France are the last gasp of a summer which cannot seriously alter the oncoming of autumn. So where does he see the smart money going? ‘The smart money would be farming in Denbighshire,’ he says.

Ruffer declines to comment on rumours that he has been buying up 50-cent Vix call options, amounting to 10 per cent of the Vix Index. This trade would be a safe move for Ruffer clients, should the stock market imminently crash. Alan and Gina Miller are among those who have doubts about the ‘50 cent’ approach: ‘If you’re worried about valuations, then what you should do is move into cash or short-term bonds, or other assets – otherwise you’re essentially betting on the 2.30 at Newmarket,’ Alan Miller tells Spear’s.

So if China or India aren’t for you, but you are attracted by the benefits of PE, where’s the place to look for good returns? Healthcare remains an attractive option. As nations become wealthier and life expectancy increases, healthcare costs are expected to rise to £10.7 trillion by 2020. Accordingly, pharmaceuticals, healthcare equipment and services all look like sound bets.

We also live in an age of data – indeed, data-related products are now considered an asset allocation in their own right. Cordelia Bowdery, an investment manager at Veritas, cites a statistic that ‘90 per cent of the world’s data was created in the last two years’, and adds that this creates demand for ‘electronic and mobile payments, data storage and analytics, fraud protection and cyber security, and IT consultants’. Wealth managers sometimes call this an innovation shock – and any analogous pocket of value can always be a smart move.

At the same time, wealth is being transferred and a well-informed younger generation is causing a spike in sustainable investment: the Donald Trumps are ceding, you might say, to the Ivankas. Jakob Meidal of Lombard Odier says: ‘In Nordic countries and among res non-doms in the UK the focus is on sustainable, socially responsible-type investments.’ But even this might be caveated. ‘In general, those who were going to go that way have already made their bed,’ says Peter Thompson. Even so, with both the EU and China ratifying the Paris Agreement – and India vowing to go beyond it – investment in this area still looks smart.

In spite of the dissenting voices, private equity remains an exciting way into these sectors – offering flexibility, choice, security and breadth of market reach. Thankfully, with the move towards transparency, this is no longer an industry where it’s not acceptable to ask questions. So the next time you see your wealth manager, you know what to ask.

Christopher Jackson is head of the Spear’s Research Unit

Recently

Revealed: Britain’s Top 100 Wealth Managers of 2017