While politicians bicker about how to fix the nation’s schools, Lord Harris of Peckham is busy getting on with the job himself, writes Charlotte Metcalf.

As debate over education and grammar schools continues, one man has quietly continued to raise the educational opportunities of underprivileged children for over twenty years. Since he reopened Crystal Palace School in 1994, Lord Harris of Peckham has been transforming dismally failing London schools. The Harris Federation now has 37 London academies, including Harris Westminster, a sixth-form school, and Aspire, a school for excluded pupils.

I confess to an interest — my twelve-year-old daughter has just entered her second year at Harris Battersea. Like so many parents, I was a ‘postcode lottery’ statistic, living just a few yards too far from the good state schools near me (Holland Park and the West London Free School). My daughter was not offered a place at any of the schools we chose, so I went in search of a school outside my area.

Last September I attended a parents’ meeting after enrolling my daughter in Battersea. The headteacher, Dr Moody, was stern as he paced in front of a handful of parents scattered sparsely around the assembly hall. ‘This school has let its community down. You see empty seats because it has failed you,’ he said. ‘But we’re changing that. Heart, head and heroism are our principles and I am passionate about every child having the best possible education and opportunities.’

I was sceptical. I did not doubt Dr Moody’s obvious integrity and passionate commitment, but I was gloomy about my daughter’s prospects in this dilapidated, ill-attended school. Yet it was his conviction that he could turn Battersea around that finally convinced me to entrust my daughter to his care. My faith was justified: the school’s latest exam results put it among the top ten in the country. When Harris took it over in 2014, only 51 per cent of students achieved five A* to C passes at GCSE level, but last summer it was 96 per cent. What’s more, 83 per cent of A-level grades were C or above — the highest score for Wandsworth borough.

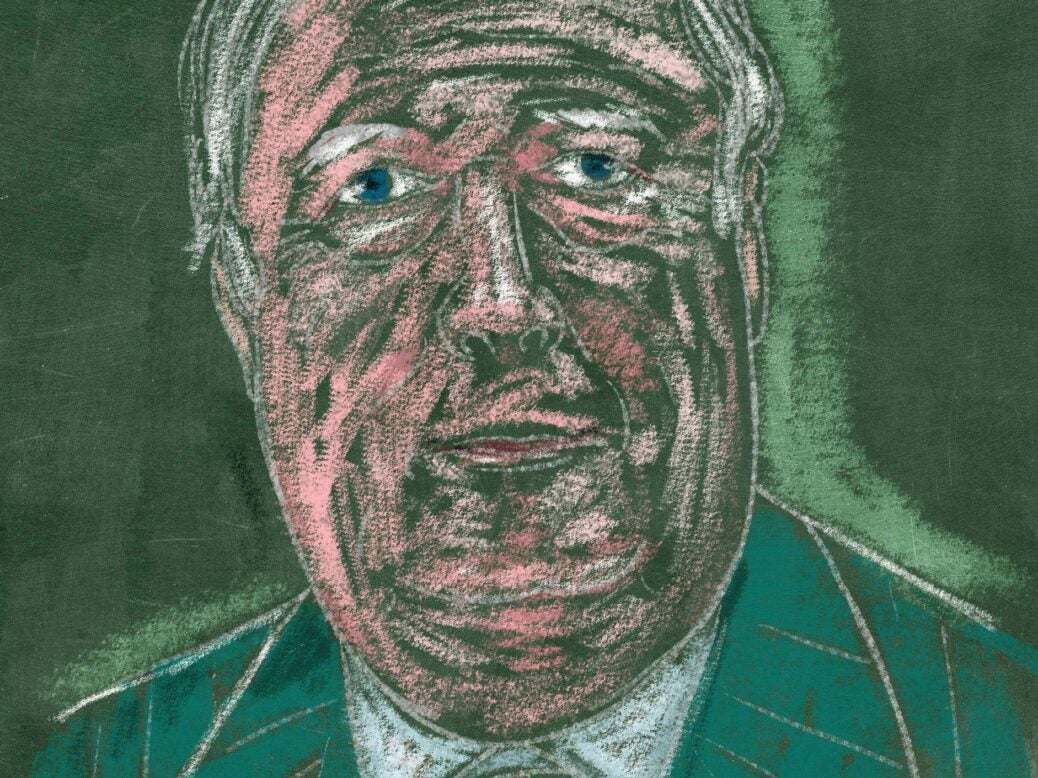

I go to Orpington, a bland suburb of south-east London, to meet Lord Harris. I already know he is a 74-year-old Conservative peer and major donor to the party, who left school at fifteen to build the family carpet business into a flourishing empire. He’s asked me to meet him at the premises of his latest carpet venture, so from the station I walk past a supermarket to an unprepossessing modern building in a small business park by a bus stop. It’s an unlikely lair for a peer and an educational hero, but it’s indicative of Lord Harris’s modesty and no-nonsense, understated approach. We meet in a bland conference room, surrounded by framed family photographs, various trophies and carpet samples.

‘In 1987 Baroness Thatcher said to me, “Philip, I want you to run a school,”’ he says after I ask why a carpet millionaire turned his attention to education. ‘I didn’t know a thing about schools but I went to see this school in Crystal Palace. It was awful. The GCSE pass rate was 9 per cent, there were only 400 students, and 50 of those were being expelled! The teachers only lasted six months. I thought, “It can’t possibly get worse than this.” So we got the school in 1990 and opened in 1994. It became the most improved school in the country, with our pass rate soaring to 54 per cent. In 2002 our pass rate had gone up to 92 per cent and now it’s one of the most popular schools in the country, with 3,500 applicants for 180 places. Over 80 per cent go to university.’

Crystal Palace’s transformation was so radical as to be magical — so what is the Harris secret formula? ‘We motivate the children with rewards and trips, we’re strong on discipline because without it you can’t teach, and if a child falls behind we give them more lessons. It’s as simple as that.’

The Harris Federation’s chief executive is Sir Daniel Moynihan, or ‘Sir Dan’. He was principal at its first Crystal Palace school. Recently, the press had a field day when Sir Dan was discovered to be earning almost £400,000 — ‘…almost three times the salary of the Prime Minister’, screamed a Daily Mail headline indignantly. Lord Harris is unapologetic: Sir Dan is the best person for the job and should be paid accordingly.

Like any high-ranking CEO, Sir Dan approaches running the Harris Federation like a major corporation. ‘Everything I say would be obvious in business,’ he says. ‘Academies need to have a clear vision to raise standards and if you have a clear model, you have to be consistent. You have to clarify to staff what the policy is and expect them all to follow it. Our policy is strong uniform, no disruption or phones during lessons, no violence, no weapons, a strong pastoral system, and we monitor pupils and chase up non-attendees and children that are late. We operate a system of tough love. The correct approach is to expect high standards, not to forgive. Less successful groups are spread all over the country and they aren’t clear as to how you do things.’

The Harris Federation trains its own teachers at a £44 million building in Westminster that also houses the acclaimed Harris Westminster sixth-form school that won six Oxbridge places for its pupils in the autumn.

‘Bad teachers affect children’s lives. We won’t tolerate them,’ says Lord Harris. (Indeed, I have seen several heads roll at my daughter’s school.) ‘Lots of teachers are stuck in the past, lumbered with old habits. Local authorities are not training them properly to use things like white boards and computers. Thanks to changes in government policy that gave us the freedom to train our own teachers, our only issue is capacity now. And we pay them more as we expect them to work harder.’ Preferring fresh young minds, the federation recruits from Teach First and as far afield as Australia, Canada, Jamaica and South Africa. Otherwise, anyone is able to apply, from lawyers and architects to paediatricians, and age is no barrier as long as they’re open to the Harris approach. Last year the federation trained 40 teachers, this year it will train 95, and next year 150.

So, does Lord Harris have plans to spread countrywide? ‘No. You can’t control schools if they’re all over the place,’ he says. ‘There’s no point growing too fast as I intend to make sure we stay ‘outstanding’ and, touch wood, we’ve never had a school that’s dropped below once we’ve achieved that rating.’

He is infuriated by constant government pronouncements on education, such as the intention to make all schools academies or reinstate grammar schools.

‘Fix the failing schools first,’ he insists. ‘There’s no point taking a school on if we can’t be successful. Even though we have comprehensive intakes at Harris, when I look at the data I can put my hand on my heart and say that our academies get the best out of everyone whether they are at the lowest or highest end of the ability range. But there is a problem nationally where too few bright children from poor backgrounds end up with the top university places and successful careers they deserve. It remains to be seen whether grammar schools are the right answer to this problem, but I am pleased that the prime minister is focusing on this important group of young people.’

Ultimately Lord Harris is less concerned with his legacy than with children: ‘I want all London schools to be even better than Harris. A school changes a life. The only thing that motivates me is making a difference to children’s education, because you only get one chance in life.’