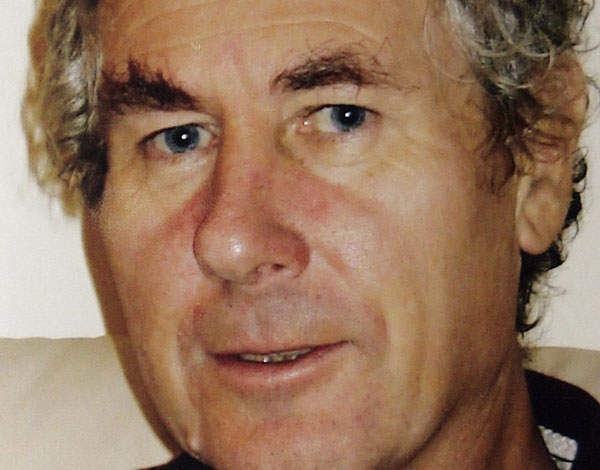

The trick-or-treaters are doing their rounds, but what if you had a miraculous and unexpected visitor? A long-lost friend, arisen from the dead? An unusual scenario but not unheard of, as the case of Ronald Stan, a pig farmer from Ontario, attests.

Ronald was found living in Oklahoma earlier this year, almost 40 years after he had been declared missing and presumed dead after a barn fire in 1977. But what does the law say about all this? When can a missing person legally be declared to be dead… and what happens if they are not?

The Presumption of Death Act 2013 came into force on 1 October 2014. Under the act, an application can be made to the High Court for a declaration that a missing person, who is thought to have died or who has not been known to be alive in the last seven years, is presumed to be dead. There is an opportunity for the declaration to be appealed but, if there is no appeal, the declaration is considered to be conclusive of an individual’s death.

The individual’s property will pass to others as it would have done had the person died in the usual sense of the word, hopefully as directed by the person’s will, but otherwise under the statutory rules that determine the way in which property passes when a person dies without leaving a will. A declaration brings the missing person’s marriage or civil partnership to an end. The court also has the power to make a declaration in relation to the domicile of a missing person.

Although the new legislation clarifies the position where a person goes missing and is presumed dead, the legislation still leaves a gap in the ability for someone to manage a missing person’s assets which, in some cases, may extend for a period in excess of seven years.

There is currently a consultation on this issue and it appears that the government will consider how best to address the legislation gap to ensure that the assets of a missing person are not left to be depleted by issues such as continuing direct debit payments or failure to maintain the assets. Specifically, the government will consider whether a guardian should be appointed to manage a missing person’s assets, or to act on behalf of and in the best interests of theperson who has gone missing. The consultation will also consider how dependants of a missing person could continue to receive the financial support that they need.

So what if it turns out that there has been some catastrophic misunderstanding? The act provides that a declaration of presumed death can be varied or revoked by a further court order if additional information is later discovered. A variation order in itself will not affect any interest in property that was acquired as a result of the initial declaration.

However, the court does have powers to make further orders in relation to property. This power to make further orders will normally only be used within five years of the original declaration, unless the court considers that there are exceptional circumstances.

Ultimately, the effects of a declaration of presumed death can be unravelled, but this unravelling is not automatic and requires court intervention. When dealing in assets that have been made available after a declaration of presumed death, it is important to be aware that this property is potentially open to challenges by a variation order if circumstances dramatically change.

However unlikely the above scenarios sound, the fact that the legal system in the UK caters for such unusual circumstances where a long lost friend comes back from the dead is a tribute to the robustness of the English laws that regulate property ownership and testamentary dispositions.

Rebecca Waterhouse works at boutique private wealth law firm Maurice Turnor Gardner LLP