In Atlas Shrugged, Ayn Rand’s novel of 1957, hard-working executive Dagny Taggart finds herself at the end of her tether, worn down by the constant barrage of excessive regulation and unproductive peers. Her response is to follow the whispers of a secretive figure known as John Galt, which lead her to a fertile, Jerusalem-like paradise – made invisible by an electromagnetic shield – where talent, hard work and ambition are allowed to remain unshackled. Its name is Galt’s Gulch.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the book has become established as a cult hit among a particular kind of person. Former Exxon- Mobil executive and one-time Secretary of State Rex Tillerson, Apple founder Steve Jobs and former Uber chief executive Travis Kalanick have all cited it as an influence.

[See also: Super-rich are giving away more of their money than ever before]

Over the years, some would-be John Galts have tried to put the book’s ideas into practice. In 1968, German-born soap magnate Werner Stiefel began a series of unsuccessful attempts to found Atlantis, a new libertarian micronation. In one of these abortive efforts, Stiefel purchased a ship with the aim of creating a community in international waters, only for it to sink in a hurricane off the Bahamas (thankfully without any casualties). Undeterred, he launched further voyages, only to find his vessels mistaken for pirate ships and forced to leave Haiti.

Attempts on land have often fared little better. In 2015 libertarian Czech politician Vít Jedlička was banned from the territory where he had hoped to establish Liberland, a Balkan ‘crypto-state’ he had planned to set up on land that was the subject of an apparently unresolvable dispute between Croatia and Serbia. The two countries did agree on one thing: Liberland wasn’t going to happen.

This litany of failures hasn’t killed off the idea of new, independent utopias. Over the past 20 years, PayPal co-founder and noted libertarian Peter Thiel has been a consistent backer of such ventures, most recently providing seed funding to Praxis. The US-based start-up proposes to build a breakaway state and has raised $525 million from funders, including Sam Bankman-Fried’s Alameda Research and Winklevoss Capital Management, the family office of the Winklevoss twins. But the project has so far proved to be more Fyre Festival than freedom land, with no physical manifestation beyond its New York office and a few expensive parties.

[See also: How citizenship is becoming a luxury asset]

Where Thiel has led, other tech entrepreneurs have followed, with Coinbase co-founder Brian Armstrong, Andreessen Horowitz’s Marc Andreessen and OpenAI chief executive Sam Altman lending their backing to new projects. Some of these have been explicitly inspired by Balaji Srinivasan, the former Coinbase executive who has called for the creation of new ‘network states’ to bring together tech optimists to build new communities inspired, in part, by the creation of Israel.

The small charter city of Próspera has only received a fraction of the attention of Praxis and other projects, but it has one major advantage: it actually exists. At the time of writing, the self-governing territory, which was established in 2020, spans 600 acres on Roatán, a 48-mile-long island off the north coast of Honduras. The island sits on a large exposed natural coral reef, with a landscape that includes powdery beaches and dense mangroves. At one tip of the island is the West End, a Caribbean-style beach town serving tipsy tourists from American cruise ships.

When I arrive at Roatán airport, I’m greeted by Lonis Hamaili, a 27-year-old Swedish national who moved to Próspera from Silicon Valley last year. He is one of 200 ‘Prósperans’ living in the charter city and works for the corporation which runs the territory as its marketing guru (or ‘VP of growth’). ‘You will spot the difference in the roads when we cross over into our part,’ he tells me as we embark on the 20-minute drive from the airport. Sure enough, as we pass the security barrier, the last metres of dirt track are replaced by immaculately smooth tarmac.

But what exactly is Próspera?

An answer to this question begins to unfold at Las Verandas, a five-star tourism resort purchased by Próspera in 2022 to expand its footprint and provide a welcoming suite to those jetting in for conferences and meetings. On a table inside, I meet Erick Brimen, the Venezuelan-born, US-educated entrepreneur who founded Próspera in 2020 and now serves as its chief executive.

Sipping a papaya smoothie and dressed in business casual – a look that seems a little out of kilter with the beach resort we find ourselves in – he launches into the Próspera pitch that has attracted $150 million in initial funding from the likes of Coinbase Ventures (the VC arm of the world’s biggest cryptocurrency platform), as well as two US- based VC funds: North Island Ventures, a crypto-backed fund co-funded by Silver Lake’s Glenn Hutchins, and Boost VC, a Californian early-stage venture fund focusing on ‘sci-fi tech’.

Technically speaking, Brimen explains, Próspera is a ZEDE (zone for employment and economic development) – an experimental charter city created thanks to a 2013 amendment to the Honduras constitution. These commercial zones can be managed by third parties (private corporations, non-profits or even other countries) who are given a large degree of freedom to set their own rules and regulations.

In this case, that third party is Honduras Próspera Inc, a Delaware-registered corporation set up by a small team of libertarian-leaning capitalists who plan to build what they call ‘the future of human governance’ – a private ‘network state’ where contracting parties can set their own rules (by consent) and thus create ideal conditions for businesses to thrive. Even better, they say, the resulting windfall for Honduras – which will reap the benefits of being the host of this nascent Silicon Valley 2.0 in the form of employment and a share of the tax revenue – will provide a replicable model for lifting other developing countries out of poverty.

[See also: Do super-rich graduates value their universities?]

Brimen says that at the heart of his vision for Próspera is an ambition to give wealth creators more of a say – within parameters – of the rules and regulations they follow.

‘In most places in the world you do business through private contracts, which give you at least some choice over things like dispute resolution,’ he says. ‘You can say that a particular contract will be resolved in the London Arbitration Centre, for example. You don’t have any say over the rules you have to follow, which are usually set in stone by a single regulator.’

Rather than impose a single set of financial regulations on someone establishing, say, a family office, Próspera allows companies to choose from a ‘menu’ of pre-approved rules borrowed from different OECD countries. In some circumstances, a company or group of companies could write a new code or framework for agreements, but they would still need to obtain an insurance policy to cover the risk of the signatories not complying with the framework or causing harm to any third parties.

‘You might come up with what you think is a great system, but you still need to convince an independent third party with financial exposure that it is as good as you think it is,’ Brimen says. ‘And they will have a much bigger incentive to supervise and scrutinise you than any bureaucrat as they actually have skin in the game, in that it’s their money on the line.’

Does such an idealistic system work in practice? A Próspera spokesperson says all the 280 businesses registered in the ZEDE have followed its minimum standard of obtaining general liability insurance in order to cover against any injuries or damages they might inadvertently cause. The corporation has its own insurer and is looking to attract other underwriters to Roatán. (‘There is also a market for insurance products in Próspera to ensure that firms are complying with their chosen regulatory framework,’ reads a prospectus document on the Próspera website.)

Brimen says many of the businesses that have come to Próspera are ‘early adopters’ drawn to the novel approach to regulation and keen to push the boundaries in terms of what would be possible elsewhere. As well as the notoriously risky world of cryptocurrency, many Prósperans are focused on ‘longevity’, the term used for various vanguard medical treatments aimed at rolling back the natural effects of ageing and unlocking supposedly superhuman possibilities.

‘They are both industries where regulators are still playing catch-up,’ says Brimen. By contrast, Próspera is happy to take the completely opposite approach, deliberately courting companies that can gain an advantage by going about their business without the strictures of a more conventional regulatory framework.

One of the more notable med-teach companies based in Próspera is Minicircle, a gene therapy start-up looking to commercialise a one-off treatment to aid muscle growth via the hormone follistatin. The company has previously been open that part of the attraction of Próspera was the opportunity to run much cheaper trials than would be possible (if at all) in the US. Last year, it received a visit from Bryan Johnson, the billionaire venture capitalist and longevity obsessive, who was happy to participate in such a trial. He has since reported that his follistatin levels are up 160 per cent.

A Próspera spokesperson says it does not comment on the individual insurance policies or regulatory arrangements underpinning individual businesses. But they do confirm that Próspera operates by the principle of ‘right to try’, meaning drug developers only have to pass ‘phase one’ safety testing before it can be commercialised.

What isn’t clear, though, is the extent to which the freedom enjoyed by businesses operating here is down to Honduras’s hands-off approach, rather than any revolutionary legal underpinning.

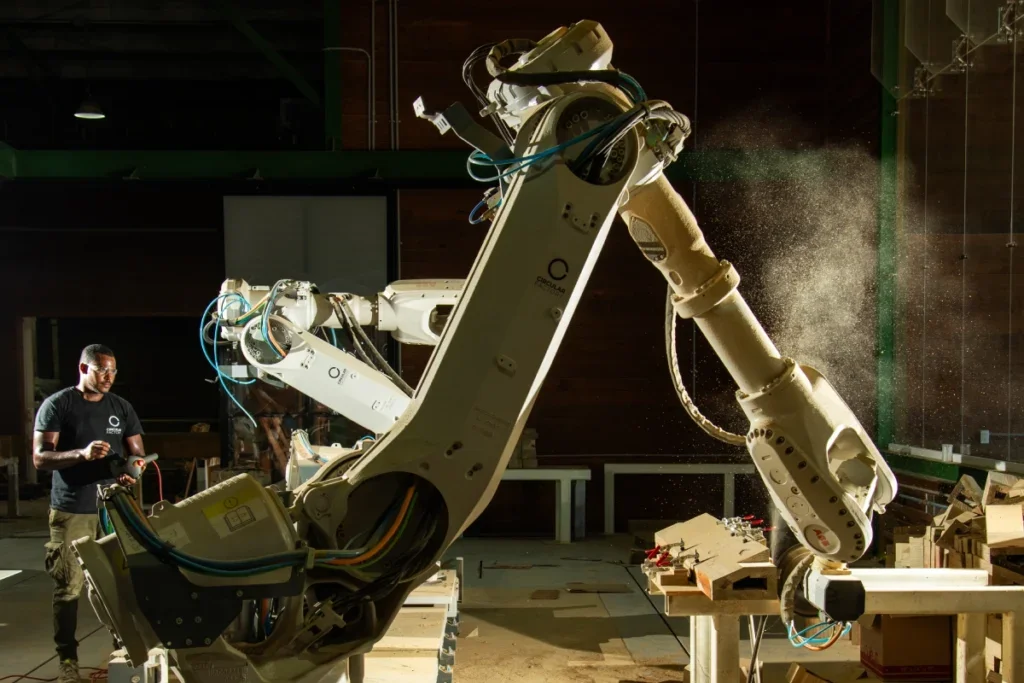

On a short driving tour around Próspera, I get the chance to visit the companies that have set up shop. They include a Bitcoin cafe and education centre; a cluster of small biohacking companies; and a boutique manufacturing plant-making components for modular homes. The Prósperans I meet are keen to stress that they see this as just the start of something bigger.

If Próspera can draw in more businesses, that obviously means more jobs, says Brimen – no small prize for a country that has historically struggled to attract private investment and where 40 per cent of the population live on less than $2 a day. But it also means more money for Honduras. Under its agreement with Honduras, Próspera pays a 12 per cent ‘revenue share’ to the central government. (Asked what that adds up to in practice, Próspera tells Spear’s it is unwilling to disclose its current income levels.)

‘What I love about Próspera is that, unlike traditional governments, they can go bankrupt, which means they have to treat you as a customer,’ says Dušan Matuška, a 32-year-old Slovakian national who relocated here in 2022 and now runs a Bitcoin education centre. ‘I love the ease of doing business here, and the fact that I can pay my taxes in Bitcoin.’

While some unsympathetic articles have sought to paint Próspera as a neocolonial hideaway for tax-dodging billionaires, Brimen is quick to reject the suggestion that it is about creating the next Cayman Islands. ‘This isn’t about just creating a destination where people can park their wealth,’ he says. At the same time, Próspera’s open embrace of cryptocurrency (Bitcoin is considered legal tender in the ZEDE) presents opportunities for those who have made their riches via such projects.

‘I think we definitely have a comparative advantage on that front if you want to move somewhere where you can use Bitcoin as a unit of account, but what we really want to do is to create the conditions for people to build businesses and generate wealth.’

Those who take up the offer will be surrounded by ideologically aligned peers, while also getting access to the parade of relevant VCs and crypto UHNWs who sometimes spring up on Próspera. Crypto-legends Brian Armstrong (he of Coinbase fame) and Vitalik Buterin (founder of Ethereum) both made visits in recent years.

For all its regulatory freedoms, Próspera doesn’t run its own immigration system, meaning anyone wanting to relocate will need to obtain Honduran residency. However, the only tax to pay is to Próspera itself (which passes on a cut to the Honduran government) and rates are low: a 5 per cent income tax, a 2.5 per cent sales tax and a 1 per cent business tax.

Then there’s the matter of actually living in Próspera. While early pitch-decks envisioned it growing into a city of 100,000 people, the current number of full-time residents is just over 200 (there are an additional 200 local workers, ranging from bar staff to security guards, who travel to the ZEDE from their homes elsewhere in Roatán). Prospective Prósperans have the option of taking on a suite in Las Verandas or renting a condo in Duna Tower, Próspera’s purpose-built residential tower. A studio will cost $130,000, while a two-bedroom apartment is $200,000.

One resident is German-born Niklas Anzinger, who relocated in 2023 to run a longevity incubator and now also hosts tech conferences here. When we meet outside the giant hot-air-balloon-sized temporary dome that hosts his latest jamboree, which is focused on crypto, Anzinger is in the process of finalising another event with Tim Draper, a prolific tech investor who made early ventures into Tesla and Twitter, among others.

For others, the influx of crypto wealth creates opportunities in more traditional fields. Próspera already has one Panamanian bank (Tower Bank) which has registered an entity in the ZEDE and recently awarded a banking licence to a crypto-payments platform called Moon. Now some predict there will soon be a burgeoning financial sector.

‘I think what a lot of people across the wealth field haven’t realised is how accustomed we’ve become to abusive bureaucracies,’ says Dylan Shub, a former family office adviser who moved recently to Próspera, where he chairs a small crypto-focused growth fund called Aurion Capital. ‘We just take it for granted that there’s going to be enormous capital requirements for banks, or that there are going to be cumbersome regulators to deal with it.’

Given the regulatory hurdles established banks can face when dealing with crypto or clients who have made their wealth in the sector, Próspera may be able to fill a gap in the market. ‘You have people in the crypto space who are looking to set up family offices or similar, but they don’t have that exposure to the traditional private wealth system,’ Shub says. In theory, Próspera’s avidly pro-crypto approach should make it an ideal place to do that.

For all the ambition, though, Próspera does have one significant risk on its horizon, which could bring everything tumbling down. In late 2021, Honduras elected a new left-leaning government whose leader, Xiomara Castro, had made no secret of her antipathy towards the ZEDE law. In 2022, Castro’s government proposed legislation to overturn the ZEDE law and thus rescind Próspera’s right to operate. The new legislation has been approved by law-makers but has yet to be ratified, meaning it is unlikely to take effect (at least in practice) before the upcoming presidential election in November.

Despite the challenges, Brimen insists Honduras remains the right destination for his project. ‘I am optimistic that either this current government will change its course on the ZEDEs or that we’ll see a more friend- ly government elected in its place,’ he says.

Not that Próspera is afraid to take the fight to the Honduran government if necessary. After Castro’s Liberty and Refoundation party set out its plans to outlaw the ZEDEs, Próspera filed a pre-emptive legal challenge to a World Bank tribunal seeking to recover damages of more than $10 billion.

In defence of his position, Brimen points out that the ZEDE legislation had expressly provided that administrators would have certainty for at least 50 years. ‘It would break my heart, but it would prove that if you don’t honour the agreements you have signed it can be very expensive,’ he says.

If the relationship with Honduras breaks down, Bremen is confident his dream can live on: it doesn’t depend on a particular physi- cal location. ‘The best way to think about Próspera is a technological platform, which will allow us to catalyse city-scale projects running on our governance model,’ he says. In other words, creating a string of similar charter cities around the world, all sharing the same flexible regulatory framework.

‘There are lots of platforms which provide software as a service, but this will be govern- ance as a service,’ Brimen continues, drawing a parallel between Próspera and the dominant model utilised by Microsoft, Google and Amazon. Próspera would then charge a fee (or tax) of 7.5 per cent for providing its governance platform. It’s an ambitious idea, admittedly, but it’s one that has been central to Próspera’s pitch to its powerful backers.

‘Erick Brimen is a true visionary, and with Próspera he is building a new type of organisation that can unlock innovation, human potential and broad-based econom- ic growth,’ says Travis Scher, managing part- ner of North Island Ventures, which invest- ed in Próspera in the most recent funding round (bringing the total raised to just over $150 million).

Will support like this kickstart a governance revolution and usher in a new age of network states? Brimen himself is a little more circumspect – perhaps wise, given the trials and tribulations faced by other organisations that have tried to create a real-life Galt’s Gulch in the past.

‘I think what we’re doing is what we like to call “MAYA”,’ he says, explaining that it stands for ‘most advanced, yet acceptable’ – a design philosophy that emphasises the importance of creating products that are innovative, while also remaining accessible and easy for users to adopt. As far as descriptions of Próspera go, it’s the best I’ve heard so far. Not a revolution, then, but an acceptable start for sure.

This letter first appeared in Spear’s Magazine Issue 95. Click here to subscribe