‘Find a job you enjoy doing, and you will never have to work a day in your life.’ We have all heard this truism. The weight of opinion on that trusted infallible source, Google, attributes it to Mark Twain (although there is another school of thought that favours Confucius). It certainly has a Twainesque ring to it, and I daresay that as apothegms go it was, fresh, funny and wise the first few hundred times its author tried it out. Now it is tainted with the banality of the motivational statement, the sort of thing that you might find in a sub-Deepak Chopra self-help book or a mediocre life coach might say.

Nevertheless, rather irritatingly there is a great deal of truth in it.

I have always liked watches. As a child I used to go round junk shops and jumble sales buying what seemed then like relics from a lost world (this was the Seventies). At university I filled the downtime between bouts of intoxication and games of backgammon in close scholarly study of Rolex catalogues. Had I actually been reading Rolex studies, I would have done better than the poor second in English language and literature that I was awarded.

When I joined the workforce, which in those days just meant wearing braces and striped shirts, my first month’s salary was taken to Christie’s South Kensington and transformed into a steel Rolex Oysterdate from the Sixties. I could not have been prouder. But why?

True, in Thatcher’s Britain, a steel Rolex was somewhere between a Filofax and Porsche on the ascending ladder of status-conferring goods… and don’t get me wrong, I enjoy status conferral as much as, if not a great deal more than, the next man. But I don’t think it was just status that accounted for my obsession with things like the helium escape valve on the Sea-Dweller and the concealed clasp of the ‘President’ bracelet that was such a feature of the Day-Date.

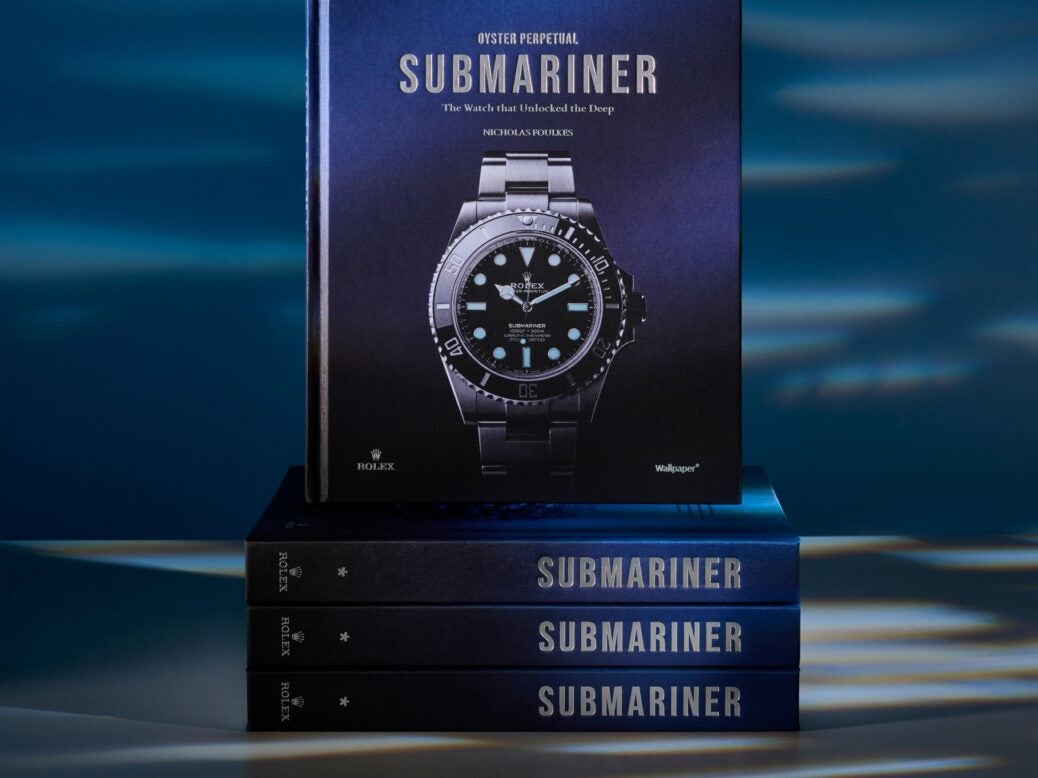

Now, 35 years later, I find myself in a position to understand a little more of the allure of the Rolex as I have embarked on writing a series of books about the brand’s emblematic models, the first of which, Oyster Perpetual Submariner: The Watch That Unlocked the Deep, was published last autumn.

It may not be Proust’s A la Recherche…, which has far too few watches anyway. Nevertheless, writing the first authorised books Rolex is a daunting task, which I do not take lightly. I enjoy doing them immensely, but they are also very hard work.

Although the book gives production numbers for the first time, I did not want to write manuals densely filled with lists and serial numbers; if I am halfway good at anything, it is not that. For me at least, it was much more significant to capture the watches in the context of their times and try to find what makes Rolex watches not just famous watches, but some of the most recognisable man-made objects of any sort on the planet. It is a privilege and pleasure to sit in the Rolex archives sifting through more than a century of letters, memoranda, minutes of board meetings and order books, while surrounded by watches so rare and recondite that few people even know of their existence. If asked to choose between a trip to the Rolex-sponsored Oscars and a day in its archives, I would select the latter every time.

While each book can be read (and hopefully enjoyed) discretely, I wanted to create something akin to a roman fleuve, a sequence of books linked by recurring characters, that carries the reader through the major events and developments of the 20th and 21st centuries, as witnessed, experienced and often shaped by Rolex watches and their wearers. Should I complete this happy task, I would hope to have mapped, however imperfectly, the world of Rolex, with each of its most famous models telling its part of the story.

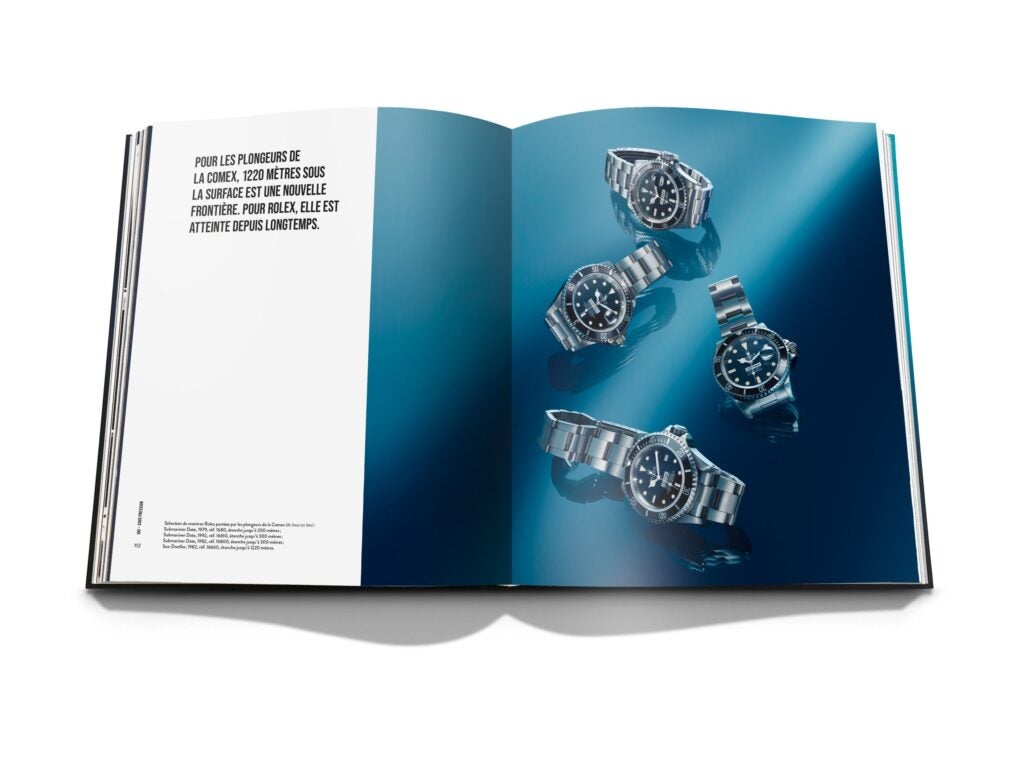

The Submariner book begins in March 1952, with British Royal Navy divers, testing the waterproofness and subaquatic qualities of Rolex watches in the icy waters of a Scottish loch, and ends in 2024 with the launch of the highly desirable, splendidly unnecessary, 18-carat gold version of the Sea-Dweller, waterproof down to 3,900m.

With the Submariner as our guide, we meet everyone from James Bond to Jacques Cousteau. We travel to the bottom of the Challenger Deep, at 11km beneath the surface of the Pacific, the deepest spot on earth. We go under the polar ice cap. We witness the birth of the first semi-submersible oilrigs, which revolutionised the business of offshore drilling. The pages teem with archaeologists, artists, actors, aquanauts, saturation divers, passionate environmentalists, Hollywood titans and visionary watch industry leaders, united by their participation in Rolex’s remarkable history. Which is also the history of our times…

[See also: Why Rolex is the sustainable blueprint off which companies should base their efforts]

This feature first appeared in Spear’s Magazine Issue 94. Click here to subscribe