Author: Sam Leith

‘Where in God’s name did the copy of Nana Mouskouri’s memoirs, signed affectionately to me, come from? I faintly remember a party…’

Legacy is one of Spear’s themes in this issue, and my legacy is by coincidence what I have been forced to think about in more detail than I would like. I’ve been moving house, see — from the LNW-thronged (the L is for ‘low’) environs of Archway to the, er, SLNW-thronged (the S is for ‘slightly’) environs of East Finchley in north London.

Moving house involves the consideration of legacy in several respects. One is that you find yourself thinking about wills and signing forms that contain phrases such as ‘on the death of X, the property will pass…’

The other is that you have to pack up your stuff. Lots and lots of stuff. There are the sticks of furniture and knick-knacks that were the legacy of your grandparents. There are the clothes — not that my wardrobe will be much of a legacy for my two kids, poor li’l rascals. And then there are the books. Half a truck consisted of dead-tree codices (I have more than the usual because I make most of my living as a writer of and about books). And these are really what my legacy, and what the legacy of any serious reader, will consist of.

Packing means winnowing (a good 20-30 feet of books have ended up at the Marie Curie shop this time; my wife seems to think I have too many), and winnowing means going through the shelves. A well-stocked private library is two things: it is a personal history in book form, a paper memory; and it is willy nilly a portrait of the culture, or some aspect of it.

On the first count, who knew (not me) what my library contained? Take, for instance, that signed copy of The Uncollected Verse of Aphra Behn — signed not by Behn, which would make it more valuable, but by its editor Germaine Greer, who addressed my school literary society two decades ago. Just handling it causes my face to flush as I remember how, stumbling over my words, I invited the whole school not ‘to join me in thanking’ but ‘to join in thanking me’.

And why do I have two copies of Victor Pelevin’s short stories? Or three copies of The Book of Heroic Failures? And where in God’s name did the copy of Nana Mouskouri’s memoirs, signed affectionately to me, come from? I faintly remember a party… Old review copies, scribbled on in my own hand; the odd valuable signed first edition; a few bound proofs I thought might end up being valuable: Roth’s Everyman; Pynchon’s Against the Day; Heaney’s District and Circle; the odd DeLillo; Franzen’s Freedom, which is less likely to become valuable since my wife spilled paint (Farrow & Ball Lamp Room Gray, I believe) on it.

Worth more in years to come, almost certainly, will be the box of old comics faithfully toted around since my mid-teens. Issue one of the Wolverine miniseries with Frank Miller’s daub on it, the first issue of ‘Mazing Man… If only I hadn’t lost the 3-D glasses that came with the first issue of Adolescent Radioactive BlackBelt Hamsters in 3D I’d be sitting on a goldmine! Is Fish Police still hot? But I digress.

Paper trail

In the world in which HNWs move, the disposition of art collections is a very big deal. Libraries: less so. Yet they are, to me, even more redolent of their collectors and more interesting and valuable in the roundest and most complex sense. Who annotates an Old Master? What does a painting tell you about the years in which it was collected — as opposed to a text, whose very edition tells a story? That paperback edition of Yeats, for instance, existed only because it appeared when the poet went out of copyright. He went back into copyright, along with lesser contemporaries, when they extended the term from 50 to 70 years after the author’s death.

To preserve, curate, add to and pass on a valuable library — and I mean valuable in more than just a monetary sense — is a great service to scholars as well as to future generations. One of my heroes, the veteran publisher George Weidenfeld, intends to pass his formidable private library to St Anne’s College, Oxford on his death. Good for him. Others should follow his lead.

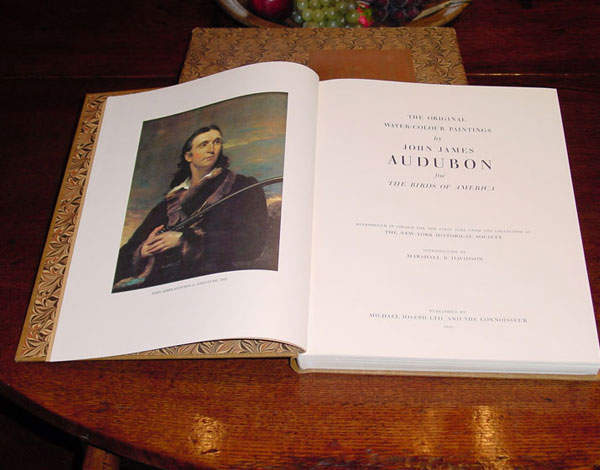

I once visited Easton Neston as the guest of a friend, and I recall the studied casualness with which Alexander Hesketh (he pretended, with aristocratic panache, to be a bit bored by these rotten old books) flipped through his first edition of Audubon’s Birds of America for me to ‘ooh’ and ‘aah’ at. He did put white gloves on, mind. No fool. In 2010, after he’d sold the house, his Audubon went for £7.3 million at auction. That’s impressive but a little sad: a library dispersed is no more than the sum of its parts. Something valuable is lost.

The libraries of the great men of any age are, I would argue, their most richly communicative and fragile legacies: they give you the man, as well as the age in which he lived. Nobody will know you better than the inheritor of the books that shaped you. The same applies, come to that, to the libraries of north London-dwelling literary hacks — however much my wife insists another trip to the Marie Curie shop is overdue.