HUNG, DRAWN AND COLLECTED

‘I’m usually there, sketching at table four, and there’s always the same woman at the next table, working on a novel on her laptop. It’s an incredible place to work!’ The Lalique-clad, opulent deco chamber that is the Fumoir bar at Claridge’s Hotel couldn’t be further removed from the traditional café refuge of the freelance creative.

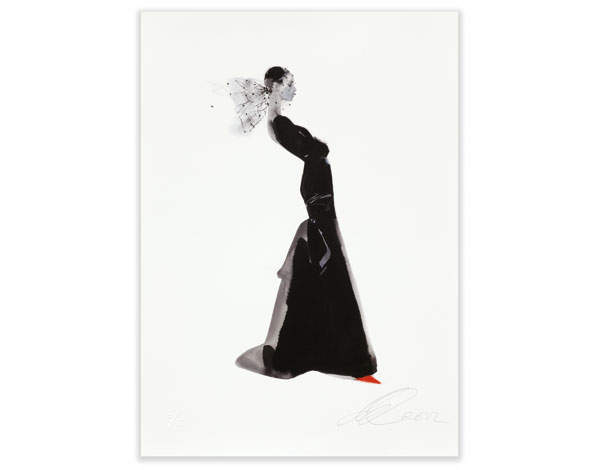

But then illustrator David Downton, Claridge’s fashion artist in residence, is synonymous with a certain kind of establishment and haute glamour. Downton is the most celebrated living fashion illustrator, and now his work — for Vanity Fair, Net-a-Porter, Tom Ford, Oscar de la Renta, the V&A and numerous other big-name clients — has piqued the interest of the serious art market.

Read more on art and collecting from Spear’s

‘With drawing, people think it’s magic,’ says Downton, as the butler arrives at his suite with tea and biscuits. ‘Everyone thinks that with the right camera, lights and assistant that they could be a photographer, but that they couldn’t do what I do. And the best thing I never did was learn how to use computers. The first stroke on the paper is so exciting. And, let’s be practical, there’s now a market in original work.’

That market has been bubbling for years. Last year saw an exhibition of Antonio Lopez’s work at the Suzanne Geiss gallery in New York’s SoHo, along with the publication of a retrospective of his sketches from the giddy style scene of the Sixties, Seventies and Eighties in Paris and New York, subtitled ‘Fashion, Art, Sex & Disco’.

This year it’s the turn of Lopez’s Eighties successor, Tony Viramontes. ‘There are Viramontes exhibitions being staged in New York, Los Angeles, Paris, Milan and China,’ says Dean Rhys-Morgan, author of the new monograph Bold, Beautiful and Damned. ‘Just as René Gruau’s work reflects the confidence and elegance of the upper classes in the 1940s and 1950s, Viramontes’ images perfectly capture the younger fashionable women of the 1980s.’

His work was also part of the pop Zeitgeist: You might not have seen his Mugler portfolio, but you’ve definitely seen the cover of the 1986 Janet Jackson album Control. As Rhys-Morgan says, ‘His work appeals to both seasoned collectors of fashion illustration and those who think it’s just pretty.’

Prevailing couture

Fashion illustration as a commercial art has its roots in the 1860s and the early days of couture. Paul Iribe and Georges Lepape’s images of Paul Poiret’s gowns in the early 20th century set a benchmark of excellence. While the rise of photography made illustration effectively redundant, it never truly went away. Now it has a defiantly analogue appeal — its elegance, flair and exclusivity make it more suited to a certain kind of fashion statement than ever before.

Downton is represented by the Fashion Illustration Gallery on Cork Street, one of the world’s leading hubs for the sale of original pieces as well as prints. William Ling established the FIG after arranging exhibitions of his wife Tanya Ling’s artwork in the Nineties and working on a show with fashion writer Laird Borrelli-Persson — one of the world’s leading authorities on fashion illustration — in 2000. ‘We went on to start the gallery in 2007,’ he says.

‘I had become connected to the best artists working in the field. Now we sell Gruau, Lopez and Warhol alongside the key living artists, including Daisy de Villeneuve, Richard Gray and Gladys Perint Palmer, whose work is witty and amusing. She hits the paper with extraordinary confidence — her thick black line crosses over into caricature.’

Early Warhol shoe drawings sell for up to £20,000 at FIG, while the most important Downton pieces go for £10,000-£15,000. These originals are gently priced when one considers quality and provenance: when several pieces of ephemera owned by Diana Vreeland went under the hammer at Kerry Taylor Auctions in London over the summer, one of the stars was a 1981 Lopez sketch of Paloma Picasso wearing Yves Saint-Laurent haute couture. It went for a modest £1,500, which was surprising given the frisson around its previous owner, its subject and artist.

Pictured above: Drawing by David Downton

Customarily, the designer and model featured in a piece of work dictate its value in an artist’s oeuvre. ‘A Balenciaga dress drawn by an unknown will not be sought after,’ says Clair Watson of 1stdibs.com. ‘A René Bouché drawing of a Balenciaga will go for more than a Bouché of an unknown design, which might sell for less than $1,000.’

‘There is no secondary market at present,’ says William Ling. ‘In terms of the art market as a whole, people spend millions when they know others share their interests, which is why people buy at auction. Individuals buy fashion illustration because they love it. It’s chicken feed, really — if you want to buy art as an investment, you want to make a big investment.’ It’s significant that serious art world figures — including the likes of gallerist Maureen Paley — are repeat customers at FIG. And where tastemakers lead…

Seller’s market

With so little supply to meet growing demand, the fashion illustration market seems certain to take off. And that demand isn’t just from those obsessed with fashion. ‘The people who collect Antonio are lawyers and businessman as well as fashion people,’ says Paul Caranicas, president of the Antonio Lopez Foundation. ‘If you look at a picture by Gustav Klimt in a certain way, it’s just a fashion picture. It’s just a matter of time before people realise it.’

Bartsch & Chariau in Munich is one of the most important galleries in the world for top fashion illustration pieces, and represents the estates of Lopez, Lepape, Gruau and François Berthoud. ‘We have the largest collection of fashion drawings from the 20th century in the world,’ says gallerist Joelle Chariau, ‘including those by artists from the art deco period for La Gazette du Bon Ton, and very early Erté drawings for Poiret.’

She believes that scarcity will drive the continually burgeoning market. ‘Fashion drawings will have the same fate as the famous original cartoons for the New Yorker. American collectors only became interested in those after most of the original material was either in museums or had been bought by European collectors, leaving only a few, very expensive originals on the market.’

It is the provenance, the historical significance, the inherent glamour and what Downton calls the ‘magic’ of fashion illustration that makes it so alluring. When Downton sketches it can be, as he says, ‘a big production… with agents, models, hair, make-up, catering and security guards sitting next to the jewellery’.

The extra element of time and handcraft that goes into each fashion illustration, like some of the haute couture that it records, makes it more significant than an equivalent photograph.

‘There is an aura or visceral reaction to illustration,’ says Laird Borrelli-Persson. ‘It is filtered through a personal take on things, with more room for interpretation than photography. It is the difference between prose and poetry.’

Pictured top: Drawing by Tanya Ling