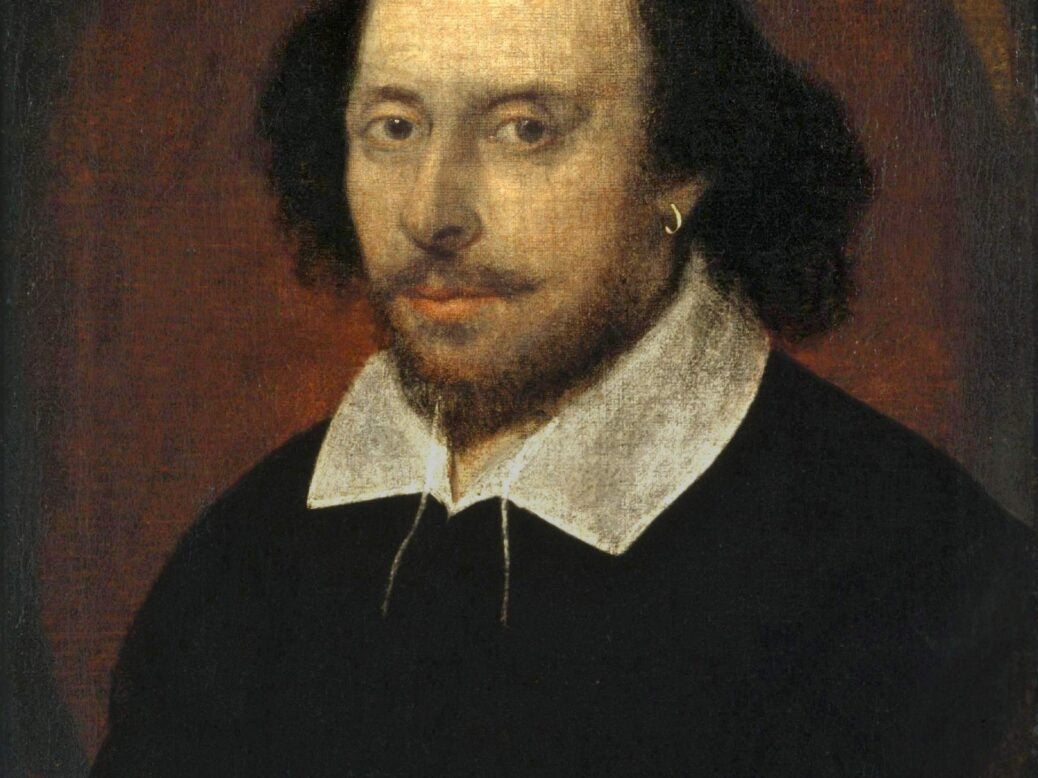

Christopher Jackson talks to industry insiders to find out what the playwright’s investments can tell us about the Bard on the week of his 455th birthday

‘Thou smilest and art still’: so wrote Matthew Arnold about William Shakespeare. This famous line gives the impression of a man who, before he became a national monument posthumously, was somehow monumental in life.

But if we look closer at Shakespeare’s activities, we find a restless spirit of enquiry – and not just as a poet as we all know, but in an area which has tended to be passed over by biographers – as an investor.

Like all of us, Shakespeare was marked by his upbringing. The prudent care he would take in his business life, shows him mindful of the variable fortunes experienced by his father, John Shakespeare (1531-1601). John – a successful manufacturer of that overlooked Elizabethan luxury item, the glove – had served as an alderman, bailiff and chief magistrate of the town council, before becoming Stratford’s mayor in 1568.

But whether due to some financial overreaching, or to a dangerously subversive strain of Catholicism, John seems to have lost standing in Stratford society; business struggled to the extent that he was forced to mortgage his wife’s estate in 1578. Shakespeare would have been 14 at that time – a scarring age at which to observe such decline.

Lessons appear to have stuck. Neil Moles, the CEO of the fast-growing wealth management firm Progeny Wealth, tells me: ‘Having come from humble beginnings, Shakespeare was focused on building a comfortable life for himself over the long term rather than just meeting his immediate needs.’

It’s that ability to think for the long term – to be patient, and strategic – which seems to distinguish Shakespeare as an investor. ‘He was very wise in that,’ says Ross Elder, CEO of Lincoln Private Investment Office. ‘I can always make money for clients over the long-term, and Shakespeare seems to have understood the importance of patience.’

Wise – but also, wise in an unusual way for an artist. In Lockhart’s great biography of Robert Burns – as disastrous a businessman as the poetic fraternity has produced – the biographer refers to the ‘contempt for futurity’ of the typical poet. Shakespeare never exhibited this.

Instead, pragmatism runs through his life – and this informs the plays too. We might remind ourselves that Shakespeare’s heroes tend to be the level-headed – people like Kent in King Lear, or Horatio in Hamlet, who seek order amid chaos, and who sustain the powerful with sound and objective advice. It’s perhaps not fanciful to view these characters as self-portraiture.

The Bard and the bull market

Moles also points me in the direction of a line in Venus and Adonis, an early-ish work: “foul-cankering rust the hidden treasure frets, but gold that’s put to use more gold begets.” It has the flavour of a personal business manifesto. Interestingly, we find echoes of this today in the big banks, where it’s not uncommon to hear advisors point out the dreary consequences of not staying invested during market downturns. ‘We’re towards the end of a bull market,’ says Charlie Hoffman, the leading relationship manager at HSBC. ‘We continue to keep advising clients to keep diversifying. Don’t go to zero and be a hero.’

Shakespeare is someone who never ‘went to zero.’ Having studied Shakespeare’s investment behaviour closely, Ian Barnard, a founding partner at Capital Generation Partners, tells me: ‘It strikes me that Shakespeare was someone who liked to be busy and who always liked to have the final say.’

How did Shakespeare diversify? In the first place, he was prepared to take advantage of innovative corporate structures by becoming a joint shareholder of the Chamberlain’s Men, which was formed in 1594. From that moment on, he would receive one-eighth of the half-share of all box-office earnings.

It’s not clear how he received the money to buy those shares, although rumours have long abounded about a possible loan from the Earl of Southampton, the likely dedicatee of the Sonnets.

For Moles, this move into shares was inspired, and would have been a constant source of security for the rest of his life, even up until his last illness. ‘His shareholding in the Chamberlain’s men will have produced comfortable dividends covering his day to day expenses and he would have experienced excellent equity growth from his holding in the New Globe Theatre,’ he explains, adding: ‘No doubt these comfortably covered off his care costs later in life.’

But if Shakespeare was patient, as Elder says, he combined that with the ability to move decisively when it mattered. Once he had begun to accumulate capital from his shareholding, he very swiftly diversified into property. By 1597, he had bought up the second largest home in Stratford-upon-Avon, New Place. This was a five-gabled affair – a statement of power and success.

It didn’t end there: after that purchase, Shakespeare moved into a connecting house and converted that into a pub. We know this because of a document outlining the Stratford residents licensed to sell ale: one of these, Lewis Hiccox, was inhabiting Shakespeare’s property on Henley Street.

This is therefore also a prime candidate for that allegedly fatal ‘merrie meeting’ with Ben Jonson and Michael Drayton in the early months of 1616. When I mention Shakespeare’s move into hospitality to Moles, his verdict is simple: ‘Ever the entrepreneur.’

What did it take to do this? Philip Eddell, Savills’ head of country house and London house consultancy team, has built a career advising the likes of Madonna and Guy Ritchie on managing rural property of this nature. He offers some intriguing insights: ‘Shakespeare was clearly happy to draw attention to himself, and must have had incredible self-belief to move from writing drama into property and hospitality. This sort of move,’ adds Eddell, ‘is not for the faint-hearted. Failure or success is there for all to see. He strikes me as someone happy to take risks and impatient for new challenges.’

There is something theatrical therefore about Shakespeare’s investments. And yet he managed this without losing sight of the detail. ‘He must have been a good delegator and judge of character to make sure he had the right people in each place to deliver what he wanted in each,’ Eddell suggests.

We think of Shakespeare as somehow alone and apart from the rest of humanity, but this observation argues an ability to interact successfully with those around him.

Even so, for Eddell there are also unanswered questions which might prove profitable areas of enquiry for historians. ‘What does he know about construction, design, modern facilities? Who does he trust to build this for him? He can obviously build to a very good quality and build to last, spending enough to impress visitors – but he doesn’t strike me as a developer building cheaply for profit.’ This observation makes the unfortunate fact that Shakespeare’s line died out within a century of his death all the more poignant.

As much as Shakespeare was presumably a delegator, there is also a sense of a powerful mind, looking after its own interests and hedging the markets against the ever-present possibility of plague and famine. Property would have hedged him against the closing of the theatres – or any sudden move of censorship by the authorities – and he also hoarded and resold grain to protect him and his family from bad harvests. It is humanising to remind ourselves that this was a man who needed to eat.

To diversify, or not to diversify?

What might a Shakespearean investor do in today’s market? Moles suggests: ‘In today’s market, his approach would certainly be fairly exposed to property and the leisure sectors, but he may have wanted to seek further diversification elsewhere. It’s likely that were the array of options we have at our fingertips in today’s globalised and digital world on offer in his time, he would have taken them.”

Ian Barnard points out that Shakespeare would likely need to think internationally today: ‘His exposure was concentrated on his local area. In today’s markets an investor needs to allocate not only across different asset classes (which Shakespeare appears to have done to some degree) but also by geography to help diversify idiosyncratic risks of each asset class.’

Does all this tell us anything about the work? Because of its profound truth, and its linguistic riches, we can easily forget the sheer common sense that informs what he wrote. This was a man who knew about things like law and money, and investment. Above all, it suggests a man who was supremely interested in all things – in the administration of life, as well as its beauty and its poetry.

‘Shakespeare reminds me of our clients,’ sums up Barnard. ‘He was successful in another industry but then used his wealth to invest in financial assets, not only to make additional gains but to protect and diversify his wealth.’ But he adds: ‘I think he would have been a hard client to win!’

Christopher Jackson is deputy editor of Spear’s