Alex Matchett’s password to the wise: HNWs are particularly appetising targets for online fraudsters.

If you’re the Duke of Marlborough and you’re staying at some of London’s finest establishments, you might as well enjoy yourself — rack up a room bill of nearly £2,000 and treat your new friends at the bar, for starters.

For a dash of intrigue, drop that the reason you’re at a hotel rather than your London place is that there is a hitman after you. Sounds like a crime novel? The twist here is almost as weird as anything Agatha Christie came up with: our aristocrat was not in fact Jamie Spencer-Churchill, as he claimed, but con artist Alexander Wood. He was arrested for fraud after fleeing his last bolthole, having been asked to show ID.

There is a sequel. A British Airways executive, Colin Palmer, visited a string of London hotels and establishments, asking for his bills to be sent to the airline. When staff became suspicious, they were put in touch with a BA employee who told them Palmer had left his luggage at Heathrow and should be allowed to stay as a VIP. Their suspicion did not abate, and they called the police, who arrested Mr Palmer — or, we should say, Alexander Wood, unperturbed, on bail from his first offence.

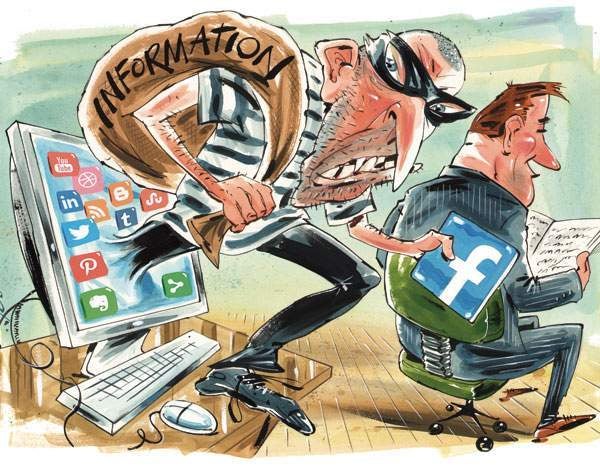

This is almost a romantic notion of a confidence trickster, but His Grace is rare among today’s impersonators: if someone is pretending to be you now, they’re much more likely to be doing so online.

‘Ten years ago, if I was talking about stealing your identity I probably did it by standing outside your house and picking up bits of paper,’ says Dave King, CEO of cyber reputation and security firm Digitalis. ‘Five years ago we started to see data theft occurring online using social engineering — which is the use of information out there about you to perpetrate crimes — and now what we’re seeing is the mass theft of data from major corporations.’

That criminals can now jigsaw together your social media and online personal information has presented a major challenge to the likes of Roderick Jones and Frances Dewing at Concentric Advisors, a US West Coast tech security firm that protects the online profiles and data of some of Silicon Valley’s billionaires, among others.

‘People with more than a million dollars of assets have definitely had a cyber-attack on them — they just don’t see it that way,’ says Jones.

They might not see it that way because online hacking has developed from mere password guessing and bombarding systems with emails into the kind of sophisticated impersonation that inspired Alexander Wood.

To highlight how cyber impersonation can affect whole companies, Dewing uses the example of Xoom, an online payment company where they estimate an employee fell for a ‘socially engineered’ scam. This involved tracking the individual through social media and sending them a tailored email such as ‘congratulations on your recent marathon’. Then, once that email was opened on a company computer, the criminals could get on to the servers, watch everything that was happening and make another impersonation.

‘They figure out the behaviour pattern of the CEO and wait until he’s on a plane somewhere and can’t be reached,’ says Dewing. With Xoom, the criminals sent an email from the CEO’s account in his voice to the head of finance requesting money for a confidential deal — and the head of finance wired out $30 million. Similar scams are alleged to have targeted a number of businesses in Australia.

But what about when an individual, rather than a firm, is targeted? Madonna’s personal computers were recently hacked, allegedly by password guessing and impersonation, unreleased tracks were stolen and it took the FBI, the Israeli police and a well-known London law firm to find the perpetrator.

Such situations shouldn’t be a surprise, says King, who points to the iCloud hacks that saw revealing photos of celebrities circulated online. That was down to simply guessing passwords thanks to information, such as pet names, posted by celebrities through social media accounts.

Another such breach a few years ago saw the hacking of a celebrity couple’s emails which were then forwarded to numerous tabloid editors — prompting a seventeen-minute injunction, the purchase of every computer in an internet café and some private eye detection to unmask the hacker.

You certainly don’t need to be famous to be hacked. One trader related how the account for their personal trades, held at a global bank, was hacked after they had made some major plays. Initially just small purchases were made, but the hackers doubled the amount each time until the fraud was discovered. Until then the trader had believed that only three people knew the account existed.

It’s not just HNW City employees with webs of assets and online accounts that are vulnerable. The greater fear now is from the orchestration of personal data and social media information to ascertain the whereabouts of an individual and their children; King discloses that he’s been able to prevent at least one kidnapping in South America.

Closer to home, one threat is that the children of wealthy families, often having emigrated from Eastern Europe, are picked up from school by gangs who then demand a ransom. With information about the family’s background, it’s not difficult for them to ascertain, often through social media, the whereabouts of parents and children at a given time. And ransoms do get paid: ‘It happens more often that you think,’ says one source.

The increasing use of social media and the reliance of security on specifics such as passwords, codes and identity have given hackers an incentive to impersonate. King mentions the recent hack of American retailer Target. ‘The attackers socially engineered their way into the air conditioning and heating supply to achieve that access — and then they sat dormant for two weeks before perpetrating the attack.’ To date, this has cost Target $252 million and the details and trust of 70 million customers.

Bodies such as the National Crime Agency have spoken about the need to educate and inform, changing our social media behaviour so we leave fewer personal details online and are more vigilant about changing passwords regularly.

Kidnapping and extortion might one day come to seem relatively minor crimes in the panoply of the digital infiltrator: Dave King predicts a murder by car hacking within ten years, saying the potential ‘is absolutely there today’. He adds: ‘I remain a digital evangelist but the reality is I spend more time now telling people not to do things online than telling people to do things online and we really all do need to start thinking about the risks.’

That’s something Concentric’s Roderick Jones echoes: ‘If you had wealth, the chances you’d be targeted by organised crime were minuscule, but now it’s almost one for one. It’s a different rule.’ The con-artist gentlemen-impersonators of old certainly seem more romantic now.