The argument for single family offices to engage in direct private equity club deals with like-minded families is compelling. The common cry from SFOs is that they want more control over where their money is put to work, so this argues against committing to blind pools — but many SFOs are still sceptical, and with good reason.

One principal of a London-based SFO has remarked to me: ‘Direct private equity for SFOs has grown in significance in the last three or so years, not least because it is perceived to have a natural governance and scale fit (since small tickets are not worth the resources used in due diligence) with the largest investing families. But the actual dangers of this approach to investing are vastly under-considered and, while it is more talked about than done, beware.’

In principle, substantial families may well be more predisposed to have the contact, involvement and control that come with direct investing. They may also see this as a way of leveraging their reputation, expertise and network, yet there is little evidence of club deals among like-minded families. Furthermore, since one key driver for a family to go direct is control, it must be appreciated that including other investors will add different agendas, risk appetites and timeframes.

One advantage sometimes cited is that a limited partner SFO might place a next-generation family member as their representative on a portfolio company’s board, yielding vital early financial experience (and only direct PE will allow this).

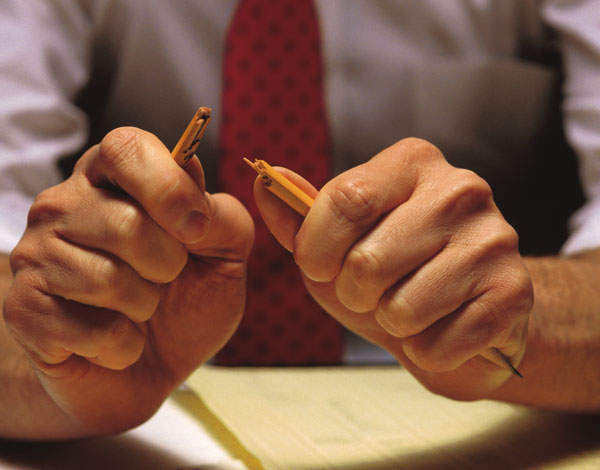

The dangers are, however, substantial. Deal origination, screening, due diligence and then ongoing administration and monitoring are parts of a skilled process that even $1 billion-plus SFOs are unlikely to possess in-house, and clubbing together with other similar families (unless one is a deca-billion outfit which can resource such broad in-house investment expertise) could compound problems but not deliver a solution.

There is also the danger of group-think; a similar culture could lead to a lack of application to the work required on the way in and a lack of suitable control during the holding period. On these points, specialist private equity advisers have a compelling case to make for ‘using the experts’. Another argument used in favour of the pooled approach is that direct PE leads to concentrated positions in a few portfolio companies, rather than greater diversification.

Perhaps the most compelling way to sow a seed of rightful scrutiny is to ask the question: ‘Why is my family being offered this co-investment?’ If it is genuinely attractive and high-quality, surely it would already have been taken or allocated by the existing general partners and their closer associates? Buyer beware.

Consider another danger endemic in SFO direct-PE investing: often the origination of such deals is through social networks (the bar at the club), which can add to excitement and appeal but vastly increase the likelihood of buying into a dog that has already been touted round more expert potential LPs who have chosen not to invest.

There are likely to be twin desires for the direct method: a legitimate desire to minimise manager cost dilution — especially the upfront fee drag on committed capital not invested — and an understandable (but often foolish) desire to be closer to the action and to do the ‘sexy bit’. SFOs rarely have the appropriate, let alone best, skill set required.

David Seligman of Seligman Private Equity Select comments: ‘GPs are paid fees because of the expertise and experience which they bring to the equation. We are concerned that many family offices do not have the requisite skills for direct investing and so should only dispense with GPs with great caution.’

Another factor to consider with direct PE is the misalignment of interests in terms of targeted return thresholds and timescales.

SFOs may have extremely long-term horizons and no foreseeable exit strategy in their portfolio companies (think Andrew Mellon and Warren Buffett). Meanwhile, GPs may be on a cycle of fund-raising (typically three to five years) and thus have an incentive to churn their best assets quickly (often between themselves). The result is huge fee dilution from churning and higher risk for the underlying LP investors associated with constantly seeking new deals (including those with a riskier profile to try to offset fees and enrich the managers).

So, we have a model with emotional attractions and certain dangers. Surely it is time for some new permanent capital models underwritten by SFOs to emerge? For a sector which can claim to have initiated private equity and hedge funds, this does not seem too much to ask.

Rupert Phelps is the director of family office services at Savills