PATRON SAINTS AND PATRON SINNERS

Patronage can be a dirty word. However good-natured it is, it all too often emphasises a distance between haves and have-nots, whether that’s between the most powerful CEO in the land and the person outside his office selling The Big Issue (itself an empowering occupation) or governments and entrepreneurs starting up with a Mac and a latte. So how can we turn patronage into partnership? We have some ideas.

As Alex Matchett’s piece on why tech entrepreneurs prefer California to Canary Wharf points out (read here), both the public and private sectors in Britain need to think in this new way. The government ought to see that its tax revenues may be augmented by the tax breaks it can offer, while the private sector shouldn’t devour start-ups for quick bucks.

Similarly, London’s wealth management firms and private banks need to start patronising the regions more effectively (read here) — patronising them in the sense of opening up branches and offering expertise rather than patronising them, as some currently do, by taking their money and condescendingly ignoring them.

<p>That would create a national dividend, as would Brett Scott’s reasonable — yet surely controversial — ideas (read here). Instead of traditional philanthropy (patronising in the bad sense), he advocates ‘philanthroactivism’ (patronising in the good sense): using your financial and corporate power for social benefits. This might be as an activist hedge-fund investor or by keeping our commons, well, common. Be a knight! he urges.

Brett Scott’s point — the point of all of these articles — is to be disruptive; the key is understanding that disruption doesn’t mean destruction, but new ways of construction. You can conceive of this construction in the broadest possible way, whether developing the networks which spawn clusters and creativity or embracing HS2 — assuming it doesn’t tear up our grand country houses — because it will better allow people, ideas and money to flow back and forth.

Essential to this is the idea of mutual benefit: good patronage is not simply giving. Philanthropy has moved past the one-directional movement of money for recognition: it’s now a crucial part of comprehending a shared economy. At its very worst, patronage can create a cycle of dependence that becomes increasingly hard to break, to the point of institution.

The opposite of that, of course, is the virtuous circle, where support, freedom and money roll around, all increasing the others. Patrons must now be partners.

PICTURE OF HEALTH

A jaunt around Mayfair these days (and is there any other way to move around Mayfair?) offers boundless artistic joys. Whether it’s English portraits of the 18th century at Philip Mould or Donald Judd’s steel boxes at David Zwirner, Philip’s Dover Street neighbour, or (at the right time of year) the Pavilion of Art and Design in the middle of Berkeley Square, it’s an aesthete’s feast.

But the gilt on that ormolu frame is looking chipped, there’s a scratch in the sculpture: something is not right in the Mayfair art world.

As we report here, a small but successful gallery on Hay Hill has closed down because their landlord wanted to treble their rent. Raphaëlle Bischoff of Bischoff/Weiss is, surprisingly, not bitter, because she sees it as a sign of Mayfair’s growth, but we can be bitter on her behalf.

A few streets over, seven of London’s oldest Modern art galleries are being chucked out of their spaces on Cork Street for a development of luxury flats and offices. On the other side of the street, further galleries are threatened by another development. The heart of the scene is being ripped out.

London’s artistic ecology, which we rightly prize, is burgeoning yet surprisingly fragile: once galleries lose their familiar, central, accessible spaces, they can either take a bold step like Bischoff/Weiss to become a consultancy — or, more likely, they will wither.

What is the point of London becoming a hyper-global, super-wealthy capital if we can’t preserve what makes this city so special?

When we end up with sleek offices where money is photocopied and no art galleries where the purpose of money is questioned, we’ll be none the richer.

GOLDEN TICKETS

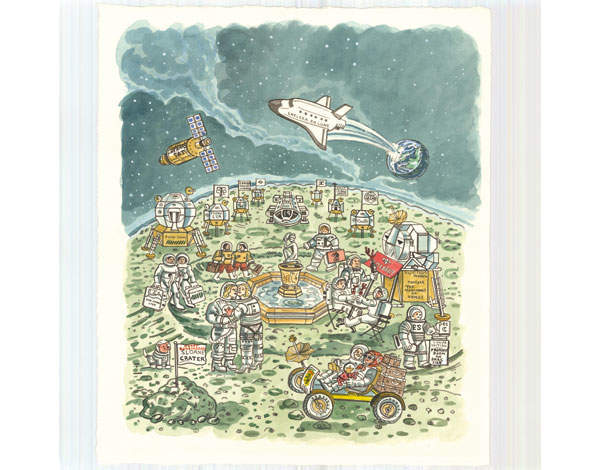

Hurtling towards the heavens at 25,000 miles per hour and being confined in a large metal box for days on end isn’t most people’s idea of a relaxing break. But at $250,000, a spell in space — the favoured holiday of financier Per Wimmer, interviewed here — is somewhat pricier than a luxury safari and certainly more exclusive than any five-star (or even seven-star) resort. After all, rocketing through space is by definition an all-star experience.

Since those of means have easier access to high-level adventure projects such as climbing Everest or touring the world via private jet, it comes as no surprise that HNWs are taking an interest in exiting the Earth’s orbit — some out of a natural sense of adventure, others as a way of showing off (what better dinner party anecdote?).

It does make one wonder, though, where the final frontier is for HNW explorers. A mission to Mars is planned for 2018, not to be confused with the one currently being organised by Dutch company Mars One, which involves a sinister-sounding one-way trip to set up a human settlement in a move reminiscent of Alien. But, if mankind does reach Mars in the next few years, will wealthy explorers stop there?

Just over 200 years ago, explorers had only just discovered Australia; in 1953 explorer Edmund Hillary was the first man to climb Everest; in 1969 astronaut Neil Armstrong first walked on the moon. All these missions no doubt required a large amount of funding and all these feats were deemed insurmountable during their respective eras. Two centuries ago, man was still discovering Earth’s land masses — now we are talking about touching down on different planets.

For many HNWs — particularly entrepreneurs — ambition, tenacity and a passion for risk will be in their blood. It will therefore probably take an earth-shattering meteorite to stop them from pushing towards new, undiscovered frontiers.