If you’ve been exposed as an affair-hunter, the law makes it tricky to get redress, says Dr Rosa Malley of Kingsley Napley

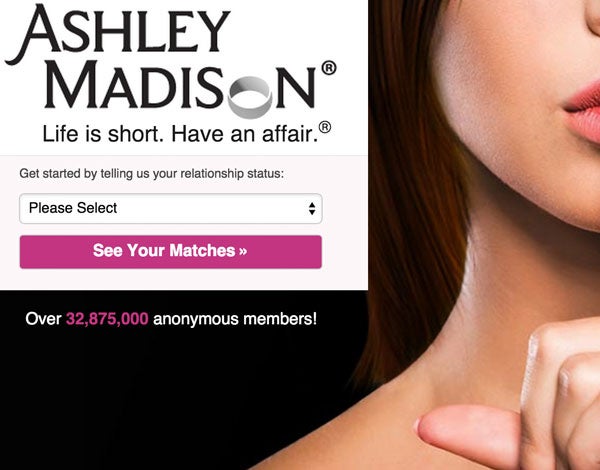

Described as one of the ‘most legally troublesome data dumps in history’, the hacking of the Ashley Madison website, which promotes itself with the tagline ‘Life is short, have an affair’, is no doubt sending shivers down the spine of any registered user who cares about their relationship or their reputation.

On 15 July, the website was hacked by a group of ‘moral crusaders’ calling themselves The Impact Team. Later that month, the hackers claimed to have released 2,500 customer records, an allegation which Ashley Madison denied.

To prove them wrong, on 18 August the hackers posted all the information onto a dark-web website only accessible through a Tor browser. Two days later they published another tranche of stolen data double the size of the first.

What can victims of this high-profile cyberattack do to protect themselves? Read more.

The implications could be devastating for the people whose marriages break down or who become victims of blackmail (which does of course have civil and criminal remedies).

There is much media speculation about the people who could emerge as users. So far, Michelle Thomson MP, a Scottish Nationalist Member of Parliament, and Josh Duggar, an American ex-reality star, are among the high profile people to be named.

To be clear, the SNP member claims she had never heard of the website, let alone registered as a member. As might be expected for such a website, a majority of real account holders tend to use false details and there is no process to ensure their authenticity. The media and the public will therefore have to be cautious about naming people.

What can someone do, however, if their name does emerge as a user, especially if they were a genuine member and provided credit card details that will confirm this?

Their legal remedies are, perhaps surprisingly, limited. It will be difficult to get the data removed from the dark-web website in the first place. The Tor browser obscures the website address from users and vice versa. There is therefore no individual or company to serve a legal notice on.

A defamation claim against a publisher who names you is unlikely to succeed. For a publication to be defamatory it must not be true. Even in the case of those unfortunate people who are falsely named, there may not be a claim for defamation.

Under the Defamation Act 2013, there is a requirement to establish serious harm. In other words, hurt feelings are no longer sufficient. Serious damage to your reputation must be established.

As commentators such as Amber Melville-Brown have recently pointed out, an allegation of infidelity may no longer be enough to damage your reputation. Unless you are a member of the clergy, allegations of adultery, or intent to be adulterous as the case may be, are unlikely to make the serious harm threshold.

A breach of privacy might be an easier claim. It does not matter whether the publication is true or false in privacy claims and you could apply for anonymity in court proceedings.

Injunctions such as the one awarded to Ryan Giggs, however, show there is nothing more eye-catching than anonymised individuals, AAA v BBB, in open court. You might as well ride naked covered only in your long hair around the winners’ enclosure at Ascot.

A breach of the Data Protection Act 1998 might be the most viable legal remedy. It used to be the case that financial loss had to have taken place in order to be awarded compensation. But recent case law suggests that it might be enough to have suffered distress as a result of the breach. Being publicly named as a registered user of a website for affairs may well fit this category.

So what is the moral of this story of morals? As the old saying doesn’t quite go, prevention is nine-tenths of the law.

Dr Rosa Malley works in Kingsley Napley’s reputation and media unit