In 2015, Ben Affleck got more than he bargained for when he took part in a celebrity genealogy show on US television. When researchers found documents revealing that the Hollywood star’s great-great-great-grandfather had been a slave owner, he lobbied for the link to be omitted. ‘I was embarrassed. The very thought left a bad taste in my mouth,’ Affleck wrote in a statement of apology after emails detailing his request were exposed.

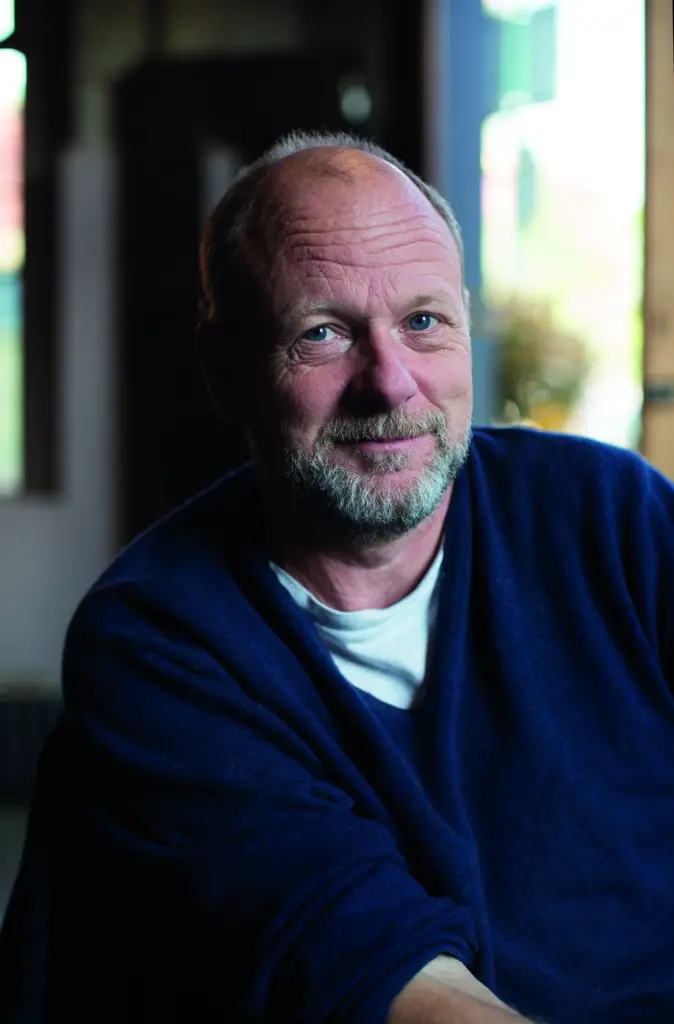

A few months later, John Dower, a British film and TV director, read about the Affleck incident in a column by the historian and campaigner David Olusoga. In it, Olusoga pointed out that similar documents were becoming increasingly accessible in the UK, revealing a side of its history that many had also preferred to leave on the cutting room floor. Curiosity inspired Dower, 61, to consult the documents, which had recently been digitised as a free online database by the Centre for the Study of the Legacies of British Slavery at University College London. It includes records of tens of thousands of British slave owners who were compensated when slavery was abolished in 1834 (enslaved people received no compensation).

‘It was quite a moment,’ says Dower, remembering the day he typed ‘Trevelyan’ – the name of the line of English baronets from which he is descended – into the database. ‘I was shocked to discover that there were Trevelyans who in 1834 received just over £27,000 in compensation, which would today be worth something between £3 million and £4 million. Thus began a journey that I have been on for the past seven years.’

That journey reflects a historical reckoning that has crossed the Atlantic in the 10 years since the Black Lives Matter movement first emerged on the streets of American cities. As institutions have grappled with the need to address and represent the past with renewed urgency, former slave-owning families face growing pressure to engage with a very personal connection to an abhorrent trade.

In April, Dower and seven other descendants of some of Britain’s wealthiest slave owners launched Heirs of Slavery, an activist movement that invites such families to join forces in calling on the UK government to apologise for slavery and start a programme of reparative justice in recognition of the ‘ongoing consequences of this crime against humanity’.

The group also includes Dower’s cousin, former TV news correspondent Laura Trevelyan, who in March said she was leaving the BBC to become a full-time slavery reparations campaigner. Other members include the Earl of Harewood, David Lascelles (a second cousin of King Charles), and journalist and campaigner Alex Renton.

‘I think we realised we had something unique, perhaps derived from the wealth and privilege of our ancestors, which was influence,’ says Renton, whose book Blood Legacy, published in 2021, recounts his own ancestors’ involvement in slavery.

[See also: How the Black Lives Matter movement is changing the world of wealth]

‘I don’t feel guilty, but I feel ashamed’

The group supports the plans for reparative justice promoted by Caricom, a political body that represents 20 Caribbean countries. Its Reparations Commission puts forward a 10-point plan for reparatory justice, asking for a full formal apology, debt cancellation, and for the former colonial powers to invest in their health and education systems.

For some, the personal response may also be financial. Laura Trevelyan pledged to donate £100,000 from a pending BBC pension payout to the University of the West Indies during a visit to Grenada alongside Dower and other relatives earlier this year. They issued a formal apology at a ceremony with the island’s prime minister, Dickon Mitchell, in which they urged the UK government to enter meaningful reparations negotiations.

‘I don’t feel guilty, but I feel ashamed,’ Dower says. ‘And I think what I’m trying to do is do the right thing, which is to atone for that shame. And I think the government needs to do the same thing.’

Yet there has been resistance to such calls, including among those who view it through the lens of the current culture wars in which reparations are labelled as ‘woke’. When challenged on the subject in parliament in April, prime minister Rishi Sunak refused to apologise for slavery or commit to reparatory justice. ‘Trying to unpick our history is not the right way forward, and it’s not something that we will focus our energies on,’ he said. A spokesperson for Labour leader Keir Starmer was anxious afterwards to signal that reparative justice was not Labour policy either.

In a Daily Telegraph column, Nigel Biggar, a priest and professor of moral theology at the University of Oxford, and author of Colonialism: A Moral Reckoning, described calls for reparations as well-intentioned but ‘absurd’, arguing that slavery was a universal institution that implicated African and Caribbean nations as well as the US and the UK. (In a sign that semantics are important in such debates, he went on to argue that Britain’s ‘moral duty’ to use its wealth to help poorer countries should include aid for Caribbean ex-colonies, but not reparations.)

Yet the families themselves feel they are facing up to their own legacies in a version of a wider, national reckoning that they say addresses generations of ignorance or revisionism. ‘My own wife and kids all used to say to me, “You’re naive if you thought that we weren’t involved in slavery,”’ Dower says. ‘But the point was that no one talked about it. If anyone mentioned it, they would talk about the affiliations within the family to the Macaulay family, who were very much part of the abolition movement.’

Dower says this reflects a tendency in British culture and education to highlight the country’s noble role in ending rather than creating the slave trade. He is reminded of the famous line by Eric Williams, the Caribbean historian who led Trinidad and Tobago to independence as its first prime minister: ‘British historians write almost as if Britain had introduced Negro slavery solely for the satisfaction of abolishing it.’

Before he searched the slavery database, Dower had understood his own family to be one of high morals and good deeds. ‘I had always got the impression that we were very sort of socially conscious, public service-focused people,’ he says. ‘And I think collectively as a society we’ve pulled the wool over our eyes, which is what makes the UCL database such a revolutionary tool. It puts it in black and white.’

Records of slavery preserved

Some descendants of slave owners were engaging with this past long before Black Lives Matter peaked in the UK in 2020, when demonstrators hurled a statue of the slaver Edward Colston into Bristol’s docks after the murder of George Floyd by police in Minneapolis had triggered a new wave of protest. David Lascelles, the 8th Earl of Harewood, is descended from Henry Lascelles, an 18th-century Yorkshire landowner and politician who became one of England’s richest men, thanks in large part to his involvement in the slave trade in Barbados. Henry’s son Edwin built Harewood House, a vast stately pile in which the current earl still has lavish apartments. (The house is now owned by a trust and run as a visitor attraction.)

In the late Nineties, staff at the house were conducting an inventory when they discovered metal boxes in a cellar. They contained documents charting the family’s sugar business, including title deeds and lists of enslaved people alongside their monetary values and physical conditions. Lascelles was aware that in many cases families had destroyed such evidence. His own instinct was to preserve and archive the files, which now make up the Lascelles Slavery Archive at the nearby University of York.

Lascelles, who has had a successful career as a film producer, has also increasingly acknowledged the family’s legacy with arts programming at the house. In March it revealed a portrait of actor David Harewood as part of its Missing Portraits series, which aims to balance the home’s collection of gilt-framed paintings of rich white men. Harewood is descended from enslaved people who were owned and renamed by the Lascelles family.

Lascelles was aware of the sensitivities of the subject even while he attempted to confront his family’s past. His father, who died in 2011, supported his son’s bid for transparency but was far more apprehensive. ‘I think he was afraid it would all just bring everything tumbling down,’ Lascelles told me. ‘And of course there was a risk of that.’

Biggar also described the Heirs of Slavery campaign as ‘politically expedient’, and said there was a perception in some quarters of virtue signalling by privileged people that may not involve meaningful sacrifice. Lascelles still owns the estate on which Harewood House sits, and the stately pile is full of highly valuable Chippendale furniture and other fine works. Why not go all the way and flog them, or the whole place, and return the proceeds to Barbados?

Lascelles has thought about this but describes a cycle of diminishing returns if Harewood House began selling the treasures that visitors flock to it to see. ‘Or if we were to sell the whole place, what would it become? A luxury hotel? An oligarch’s country home? I don’t know that any of those things are a more valuable social asset than the one we have now.’

Lascelles and his fellow heirs are aware that their position of privilege makes any response difficult, whether they continue to look away from their families’ past or face it. He is also not averse to giving, and 10 years ago he donated almost £80,000 to a Caribbean community arts foundation in Leeds. The money had come from the sale of rare rum found in the cellars and made with sugar from the Lascelles plantations.

‘No one talked about how we became wealthy’

The earl is well positioned to advise families who have more recently started similar journeys on the moral complexities of their desire at least to do something.

‘It’s been quite painful in my family,’ says Renton. Like Dower, he says his family had told itself positive stories of brave soldiers and great philanthropists. ‘No one talked about how we became wealthy in the first place. Most of us are prepared to do so now, but one or two relatives have said, “You have betrayed our honour.”’

Dower’s immediate reaction on seeing the Trevelyan name in the slavery database was to confront his father. Yet he said he didn’t know the extent of the family’s involvement either. ‘He was very supportive, but there are other members of the family who have said things like, “Why should we apologise for something we didn’t do?”’

Renton has also visited the Caribbean and the site of his ancestor’s former plantations in Tobago and Jamaica. As Heirs of Slavery starts the long and perhaps uphill challenge to push for change across society, he says words have had as much power as financial commitments, which are a personal decision when taken by families themselves.

‘From grandmothers living in smallholdings on the plantations to Jamaican politicians and academics, lots of people told me that they never thought “you white people were going to say you were prepared to talk about this”,’ he says. ‘And it was in my gift to say, “I’m not in denial about this and that I’m going to listen and try to understand what you feel about it.” And that’s what Heirs of Slavery is: a collective voice that starts to say not all middle-aged posh white people want everyone to shut up about this.’