Fez is a bustling, car-free metropolis that never stops — but centuries of history open up when you take a walk through its narrow streets, writes Alba Arikha

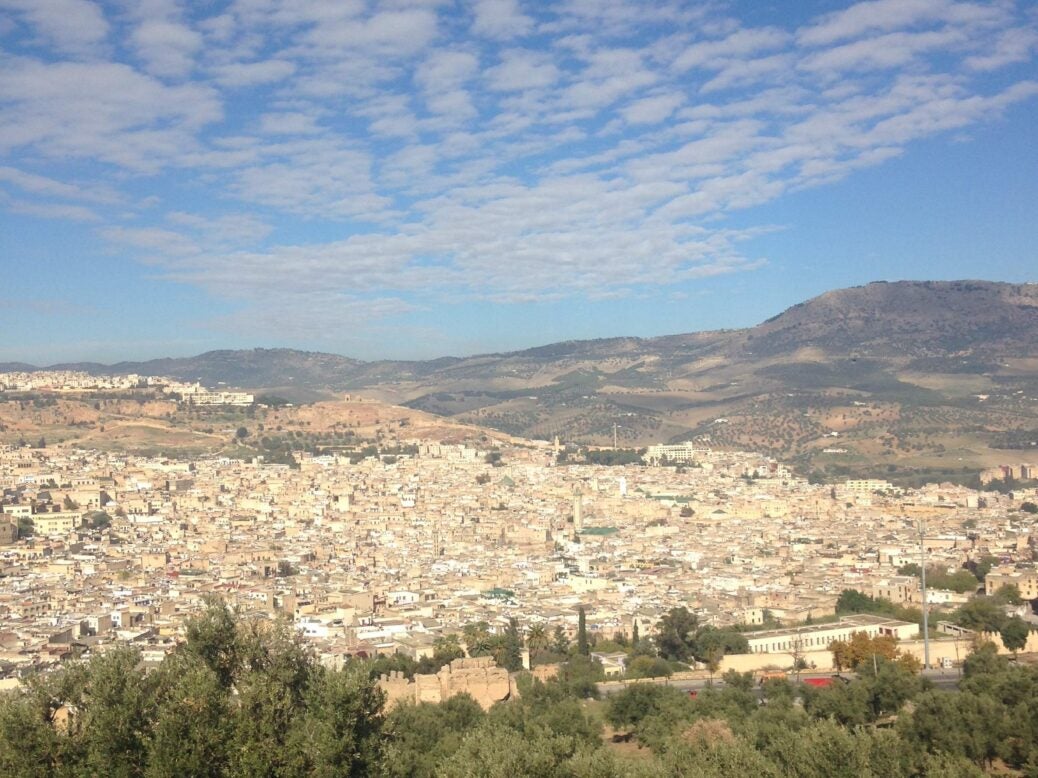

Driss, playwright by night and tour guide by day, suggested we drive to the top of the hill, above the great walls of Fez, in order to get a panoramic view of what awaited us below. The city, with its patchwork of minarets, madrasas and satellite dishes, glittered in the hot sun. The Atlas mountains loomed in the distance.

A detour to the Art Najiceramic factory, where men were glazing and firing mosaic tiles (crafts are sold all over Morocco, but Fez and Safi are where they’re made), was our last stop before we entered the medina through the main blue gate, theBab Bou Jeloud. From there, we followed the main artery of the Talaa Kebira (‘big hill’) into the heart of the medina, a sinuous labyrinth of alleyways inside the city’s pockmarked walls.

Fez is a city of settlers: Berbers, Turks, Romans, Byzantine Greeks and Moors. It was founded in the 8th century, on the banks of the Jawhar river, by Idris I, a descendant of the Prophet Muhammad. The popularity of King Idris may have pleased his people but not the Caliph of Baghdad, who sent his poisoner to ensure the King’s untimely demise. He hadn’t counted on Idris’s wife being pregnant, though, or for her son, Idris II, to fulfil his father’s vision. which he did, and well.

The name ‘Fez’ derives from the Berber word faz, or ‘pickaxe’. Idris II is rumoured to have used a golden axe when he drew the lines that would divide Fez in two: Fez El Bali (the old medina) and Fez Jdid, a continuation of the medina, or ‘New Fez’, as it is called — ‘new’ dating from 1276 (the Ville Nouvelle was built in the 20th century). The city, shaped like a bowl, soon grew in size and importance: in AD 859, Fatima al-Fihri, who had fled her homeland of Tunisia for Morocco, established the Al Qaraouyine University, said to be one of the world’s oldest surviving institutions. This imposing building, forbidden to non-Muslims, houses 20,000 worshippers, and marked Fez as the spiritual centre of culture and learning. By the 11th century, during the Almoravid dynasty, the empire of Fez stretched as far as Senegal. By the 14th century, it had become a refuge for Jews, who enjoyed the favours of the Sultan.

The Jews have long gone, having emigrated or moved to the Ville Nouvelle, but its cemetery of blindingly white tombs is a ghostly reminder of their presence. Everything about this 8th century imperial city, the capital of Morocco until 1925 and now a World Heritage Site, is a constant reminder of its thriving past.

Instead of cars (it is said to be the largest car-free urban space in the world) there are donkeys, and plenty of them, their backs piled high with vegetables, sacks of spices, bricks, television sets or laundry. There are 9,500 alleyways so narrow that only small patches of sunlight can filter through.

On our walk, Driss pointed out hidden gardens and restaurants, fountains and riads. When we set off on our own the next day, we met a kindly man who beckoned us through a small door into a treasure trove of a 200-year-old riad. Around the corner from Riad Salama, the proprietor, Lajaj Ali, sold Berber carpets, percussion instruments, and a most enticing collection of Fassi pottery.

Riad Idrissy was equally enchanting, as was its owner. It is the brainchild of Robert Johnstone, former reservation manager at the Wolseley and the Ivy, and John Twomey, of the Ten Bells pub in Spitalfields. Today, Johnstone is designer, gardener, cook. This ruin of the 400-year-old palace was bought in 2006 and meticulously restored, with terracotta tiles, painted cedar doors and delicate stucco work. The five suites are decorated with materials and antiques sourced in Morocco. Everything here is understated and traditional, and the staff are among the nicest I have ever come across.

The restaurant, the Ruined Garden, is excellent (the eggs Berber, its breakfast special, are not to be missed). Johnstone grows his own herbs and vegetables and smokes his own salmon. Specialities include Sephardic poached chicken, a tagine of artichoke and chickpeas, and chicken Volubilis, inspired by the ancient Roman writer Apicius, to be sampled after an essential visit to the wondrous Roman ruins of 3rd century BC Volubilis. Every visit to Fez should include this archaeological gem, its Roman arches and remarkably conserved mosaics open to the elements.

The medina of Fez is said to house more than 100 mosques, 60 fountains (the 17th century Nejjarine fountain is worth a detour), 250 hammams, and hundreds of bakeries (bread and baths, like religion, are of notable importance here). And finally, unlike its more famous counterpart, Marrakech (‘You don’t smell Morocco there,’ we were told, by a solemn shopkeeper), Fez has remained impervious to the demands of capitalism. This is not a destination for the designer shopper. That’s not to say it doesn’t have its share of boutique hotels: but walking through and getting lost in this 1,200-year-old maze is like living an anachronism. Money may have poured into the city, foreigners may have bought up its abandoned riads, but one gets the distinct impression that little has changed here since medieval times.

The artisans in the medina (engravers, soap makers, and more) are divided into small districts, and each has their allocated place within the souk. Potters and weavers with large looms jostle for space next to tailors and bakers. Men beckon us towards their carpet shops — ‘Come in, I give you first morning price!’ — while a posse of tourists take pictures of the marble columns of the must-see, cedar-domed al-Attarine Madrasa, completed in 1325. Farther along we stop at the Place Seffarine, the open 18th-century square of coppersmiths and tinkers who hammer copper and brass, the sound drifting over a muezzin call to prayer.

We set off for the 11th-century Chouara tannery, one of the city’s most memorable sights. Fassi painters are the most sought after in Morocco and every imperial city is associated with a colour: Red Marrakech, White Rabat, Green Meknes, Blue Fez. Men once crossed the Sahara for pigments, and looking at the open vats, one can see why. Fez’s tanneries are spread out like an artist’s palette: indigo blue, mint-green, saffron yellow, pimento red, and pomegranate powder which is said to turn the hides yellow.

If you want to buy the leather you won’t have far to go: the numerous vantage points to the tanneries are lined with shops so that the inevitable buying takes place either before or after your visit, as it has done for centuries. When the Italian journalist Edmondo De Amicis visited in 1875, he wrote the following: ‘We cross, jostled by the crowd, the cloth bazaar, that of slippers, that of earthenware, that of metal ornaments, which altogether form a labyrinth of alleys.’

Not much has changed. Fez is a timeless city of movement, of continuous motion until nightfall, when its 150,000 inhabitants slow down. We ate at Dar Roumana, run by a French chef. Children played football in a narrow alleyway, streetlights throwing their shadows against the sandstone walls.

We spent the last evening at Le Jardin des Biehn, a palace restored by French antique dealer Michel Biehn. At dinner in his restaurant, Fez Café, he told us how he had stumbled upon it during a visit to Fez in 2008. ‘I thought I’d live in Istanbul,’ he said. ‘But instead I ended up here.’ ‘Here’ is the sumptuous summer house of Tayeb El Mokri, the Pasha of Casablanca, son of the Grand Vizir. Built in 1906, it is set around an Andalusian garden. Biehn arrived with a lifetime of collector’s artefacts: decorated with sumptuous antiques and textiles, the rooms echo Biehn’s journeys. We stayed in the Sultanas, the Harem apartment, and slept below a signed photograph of Henri Cartier-Bresson. The Pasha suite belonged to the man himself and is worthy of his name: this is opulence at its most tasteful. In the morning, we had a last cup of coffee with Michel. As we were leaving, he told us a last anecdote about the Pasha, a music lover. ‘He was the first to bring a Steinway grand piano into the medina. And then he devised a way in which music could be heard from every room.’ Those words still resonated as we boarded our plane.

Alba Arikha is a freelancer writer for Spear’s

This article first appeared in the Spear’s Travel Guide 2018. For more, visit: https://spearswms.com/luxury/travel/