Sam Leith revisits his childhood favorite Ray Bradbury, and laments the demise of the age when magazines published short stories

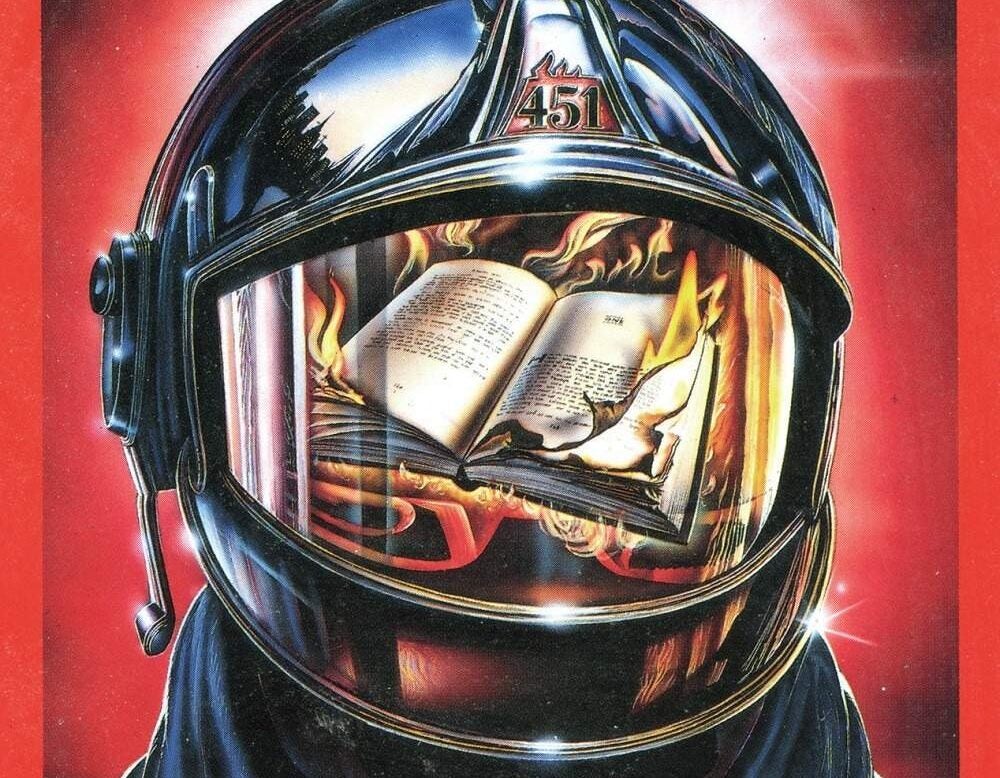

I’ve been thinking recently about the great science-fiction writer Ray Bradbury, as I was talking about him as my old friend Andy Miller’s guest on the Backlisted podcast, which concentrates on neglected and out-ofprint books. He’s best known for his dystopian novel Fahrenheit 451, but my love for Bradbury comes out of my childhood reading of the short stories in the two-volume 1983 Grafton paperback edition. Just the covers – red and yellow for volume one; green and yellow for volume two – take me immediately back to the playroom of my parents’ house in Surrey in the mid-Eighties.

That’s apt. To read Bradbury is to travel – each story creates its own world, the best of them are based on the sort of image or idea that stays with you for years, and they range from the past to the far future, from the green grass of Bradbury’s childhood home of Waukegan, Illinois to the canals of Mars. Here are stories filled with the sinister and strange: rocket ships, dinosaurs, time-travellers, vampires, and the simultaneous excitement and chill of an ominous carnival blowing into town.

Without Poe and Wells and Verne and Lovecraft, Machen and Edgar Rice Burroughs, there’d be no Bradbury; but without Bradbury there’d be no Stephen King, no Jeff VanderMeer, no Asimov, no Neil Gaiman, no Spielberg. He invented half the tropes of modern sf and fantasy and horror before those genres were even thought of that way. But to read Bradbury is also to travel in a different way: to travel in time.

The publishing ecosystem that nurtured his work has, more or less, vanished. In the short memoir Drunk, and in Charge of a Bicycle with which my edition of the stories was prefaced, he wrote about the early experience of selling his stories: ‘I mailed off three short stories to three different magazines, in the second week of August 1945. On August 20, I sold one story to Charm, on August 21, I sold a story to Mademoiselle, and on August 22, my 25th birthday, I sold a story to Collier’s. The total monies amounted to $1,000, which would be like having $10,000 arrive in the mail today. I was rich. Or so close to it I was dumbfounded.’

There’s a paragraph you could simply never read now. That $10,000 (the memoir having been published in 1983) would be about $25,000 now, for three short stories from an

unknown writer – and few of Bradbury’s short stories were more than ten pages long.

SHORT AND SWEET

But this was the age when magazines published short stories – and paid a small fortune. Philip Hensher, in his introduction to the recent Penguin Book of Short Stories, bitterly laments its vanishing. Not only do you no longer get paid much to publish short stories: there is barely any longer a periodical market for short fiction at all.

Yet this was an environment which, outside the rarefied world of ‘literary fiction’, not only enabled many writers to earn a good living: it produced some of the most remarkable work. We needn’t, probably, allude to the serial publication of Dickens – nor to the fortune that Arthur Conan Doyle made out of The Strand Magazine. The pulp writers of the early and mid 20th century – Mike Moorcock and JG Ballard caught the end of it – were inheritors of that tradition and sustained by it. Philip K Dick, Dashiell Hammett and Raymond Chandler would have been nowhere without the pulps.

And, of course, literary short fiction too had its place in periodicals. Norman Mailer, Tom Wolfe and Joseph Heller all published in magazines like Playboy and Penthouse – as did Marquez, Murakami, Roald Dahl, James Baldwin, Ursula LeGuin and Joyce Carol Oates. Not a bad result for the many men who ‘only read it for the stories’. Bradbury, to start with, sent his ‘respectable’ stories out under a pseudonym.

SERIAL KILLINGS

Periodical publication had an influence not only in allowing great writers to make their careers possible; it influenced the form. The shape of Dickens’s novels was determined by serial publication. And writers like Bradbury were, for better or worse, influenced by the need to be salesmen. Nobody knows how many short stories Bradbury wrote – around 400, it’s thought. But they were constantly retitled, repackaged, respun.

Fahrenheit 451 started life as a couple of unrelated short stories: he took nine days to bosh three of them into a novella, and took another nine days to turn that novella into a short novel. A number of Bradbury’s novels, such as The Illustrated Man and The Martian Chronicles, are ‘fix-ups’; old stories linked together with a frame story. Chandler was notorious for making ‘novels’ by gluing a couple of old short stories together and respraying them like a used car.

We’ve treated the recent vogue for novels that are halfway to being collections of linked short stories as an exciting literary innovation. Really, it’s a return to the old days and

pulp writers got there first. Maybe there’s a lack of high artistic purpose in this way of doing things – but there’s a marvellous energy and vigour and inventiveness. Literary fiction has nothing to match it.

Photo credit: RA.AZ @Flickr

Sam Leith writes for Spear’s