There’s something they say in St Barths: ‘It’s so different here from the rest of the Caribbean, because there’s never been any slavery.’ What they really mean is that there wasn’t any of that vulgar slavery — the sweaty stuff of plantations and the sugar trade. In reality, the duty-free status of St Barthélemy made it a key slave market for the Swedes, who had custody of the island from 1784 to 1878.

Long before the smooth calfskin ‘Chain Louise’ Louis Vuitton bag became a must-have accessory on the island, more prosaic chains were all the rage. The industry put the island on the map: there was little of agricultural value. Soon, with no import tax on slaves and a 50 per cent off deal for Swedish traders shopping for them, there was a port, streets and a town hall. Today, that infrastructure has been put to use for a glossier commerce and a playful approach to taxation. But beneath the gloss, conflict stirs.

It’s difficult, at first, to tell what’s real and what’s not in St Barths. The oxygen oozes fragrance and money, like the backdrop for one of JG Ballard’s dystopian Cocaine Nights-era novels. The coastal drive from airport to hotel takes you past some of the world’s weirdest cemeteries, each filled with immaculate white marble graves and headstones covered in an unsettling, psychedelic mixture of lurid fake flowers — it’s theatrical, or weirdly cinematic, reminiscent of the opening of Almodóvar’s Volver. ‘It’s beautiful on All Saints’ Day,’ says my taxi driver. ‘People come and converse with the dead by candlelight.’

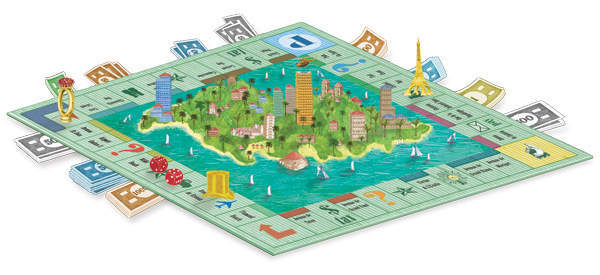

The most unsettling conversations on the island in recent years have centred around Monopoly-style intrigue. In 2012, Isle de France hotel owner Reverend Charles Vere Nicoll handed management of his property to Oetker, the family-run company that so capably oversees the Lanesborough and Le Bristol in Europe. In 2014, however, Oetker was ousted by LVMH and its Cheval Blanc brand. What Bernard Arnault wants, Bernard Arnault gets. But then — with a final gasp of triumph — Oetker took over management of what may be the ultimate St Barths icon: the Eden Rock.

Monied snowbirds are the lifeblood of the tourist industry here, and are loyal to their favourite properties. The Eden Rock regulars will argue that Oetker got the better deal: the red-on-red Sand Bar feels like the centre of the St Barths universe, while Jean-Georges Vongerichten’s On the Rocks, built around and on top of Eden Rock itself, is one of the world’s most iconic dining rooms. From the giant red stiletto at reception (a sculpture by Richard Orlinski) to the vast suites of various design and theme (the Howard Hughes Loft has three terraces and an en-suite bathroom built out of what look like retro Lockheed aircraft panels), Eden Rock is more irreverent and effervescent than the pink and white peace and quiet of Cheval Blanc. You watch women stroll into the sea no deeper than waist-high in Proenza Schouler swimwear and diamond earrings and realise it could all slide into meretricious territory, but it never does. This is what 5 Hertford Street and the Upper East Side look like on holiday. To slum it, they stroll around the bay to Nikki Beach.

St Barths is best known for being a ringfenced island of peerless luxury. Immigration is difficult and largely in one direction: France to St Barths. It’s a very attractive proposition: if you can afford to settle, you’ll live tax-free after five years. Nearly all the service staff are white, French, svelte, tanned and comely (and that’s just the boys). But none of them will ever achieve tax-free status. ‘They work here for six months and then go to the south of France for the summer,’ says Martein van Wagenberg, MD of Le Guanahani, which absorbs a huge chunk of seasonal labour. No one is buying property on St Barths on a waiter’s salary: in the busiest of years, just twenty or 30 homes change hands, ranging in price from €1 million to €25 million.

This is a holiday island, defined by transience, with a profoundly peculiar population. ‘There are three kinds of people living here,’ says Juan Carlos Perez Febres, one of the restaurateurs behind Bonito, everyone’s favourite hilltop destination. ‘There are the Portuguese construction workers; there are the Parisians, who are hated by the locals because they’re arrogant and don’t say “Good evening”; and there are the natives, who all belong to a few families and are billionaires but don’t behave like it. They wear flip-flops and shorts, have distinctive cheekbones and don’t go out much. Although some of them drive cabs, just for fun.’

Those families own just about everything. While St Barths has been a Collectivité of France since 2007 — casually adopting an Anna Wintour facial expression while cutting all ties with its ugly and impoverished sister Guadeloupe — it’s the early settlers’ offspring that have the power. Bruno Magras’ surname was a household name before he became president in 2007; ditto Senator Michel Magras

‘The families have history,’ says David Matthews, majority owner of Eden Rock and partner of Oetker there. ‘They remember what it was like when their ancestors were clinging to a rock in the Caribbean Sea with nothing. They are very protective and they don’t want a bigger runway at the airport or a developed port for cruise ships.’ St Barths only embraced on-grid electricity in the 1960s, and broadband internet in the mid-Noughties.

The families haven’t always had a smooth ride, though. A few years ago Manhattan hotelier Andre Balazs threw money at a plan to open an ‘eco resort’ that didn’t, to many, seem eco at all. Magras was said to have waved Balazs’ plan through with all the exuberance of someone being led to the best table at Chiltern Firehouse — but the locals saw the through the greenwashing. Theyprotested, and made the project disappear.

There’s something of the Wicker Man about St Barths — it’s a village where everyone knows one another, and any time Magras has been deemed to misbehave he’s been called on it, such as when municipally accorded contracts were awarded to private companies in which he had a vested interest. (Nothing was proved.) There’s a touch of the benevolent patriarch here: when you fly in to St Barths, it might be Bruno that flies you in — Magras has his own airline, St Barths Commuter. Mostly, people love him. He’s one of them.

The island is shamelessly exclusive. Which is its appeal. When the Thomson cruise ships drop anchor an acceptable distance out from the main town, Gustavia, they disgorge ferryload after ferryload of nonplussed British passengers, fish out of water to a Primark-wearing man. These visitors may pick up a few diamante-emblazoned souvenir T-shirts, but they’d baulk at the prices at the bordello-like Le Ti restaurant, a kind of Moulin Rouge for the yacht-owning classes. And you won’t find them enjoying the sunset from the balcony tables at Bonito, drinking Coconilla Chanel cocktails and tucking into ceviche and lobster risotto.

The island is busy upgrading itself in line with the expectations of the next generation of its super-wealthy guests — when you’re paying $5,000-plus a night for a suite, you want all mod cons. Most recently, Le Guanahani has emerged cosmopolitan and chic from a $40 million refurb. Its candy-coloured villas, with contemporary four-poster beds and snazzy minibars and furniture styled by interior designer Luis Pons to look like vintage travel trunks, are fresh and inspiring. Tortoises roam the tropical landscaped gardens and there’s a Clarins spa.

St Barthélemy makes a virtue of its sky-high cost of living. And by nature of its borders — not its geography — it’s very white. Guadeloupe, its nearby soeur, must be tropical green with envy, living on handouts from France, with high unemployment. St Barths, by contrast, takes nothing from the Republic. There’s zero crime, Starbucks will never happen, and what counts as your corner shop stocks Meursault. St Barths’ government is small and prepared to make all the right moves to make sure things are only going to get better. Who wouldn’t want to live there if they could?