Spellcheck and predictive text software are accelerating the homogenisation of language and at the same time arresting its evolution. It’s also a nightmare for Emelia Hamilton-Russell

I’m considering changing my name. And no, it’s not because I want to dump the cumbersome double barrel (as Sophia Money-Coutts says, it’s character-building). What bothers me now is the first bit. As probably the hundredth email arrives in my inbox addressed to Emilia, rather than Emelia, it seems the whole world is insisting that my name on my birth certificate is a typo. The trouble is, I’m beginning to think they might have a point.

A quick google confirms my suspicions. The ‘experts’ from Nameberry, a baby name website, say this: ‘Emelia takes elements from soundalike [sic] sisters Emilia and Amelia, which actually derive from different roots and have different meanings. So rather than cobbling the two together, it’s better to make a choice. Rival or work? Latin or German? Pick a lane and stick to it.’ My parents obviously didn’t get the memo.

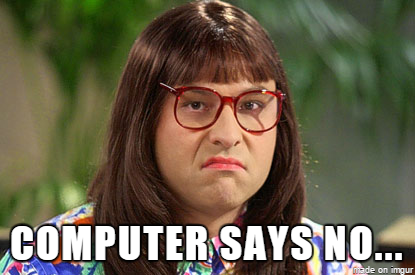

But if my name is too ‘computer says no’, some of my colleagues have it worse. Alec becomes Alex nine times out of ten, and my colleague Rasika gets addressed as anything from Rachel to Ruskin. Arun gets a red squiggly line, or depending on the context, changed to ‘a run’. I’m guilty of this modern email etiquette foible, too. I recently sent an email to ‘Angus’, who politely wrote back to tell me that his name is actually Anul.

It’s more than just an annoyance. It speaks to a wider concern about how technology is altering our lives in ways that are unpredictable and unprecedented, and control freaks like me are right to be concerned. Spell-check software – like social media and petrol-fuelled cars – is a technology designed to be helpful that has surpassed its utility and become a hindrance. Our phones and computers are so quick to second guess our intentions that we have to be constantly on the back foot, poised to re-correct the mechanical correction. While humans are adaptable creatures, it sometimes feels like there’s a miniature, curmudgeonly, homogenising editor sitting inside my computer and maliciously trying to trip me up. In a way, it’s also creating its own social change because sometimes it’s easier to conform to the software’s unimaginative suggestions. But turn it off? No way.

Interesting, too, is the rise of sites such as Grammarly, which promises to make you a better writer by checking your text against ‘over 250 grammar rules’. While I appreciated the free but partial plagiarism checker when I tried Grammarly as a student, I dumped it when the system started flagging up any sentence written in the passive voice. It’s true that active is often better than passive, full stops are often better than commas – but there’s no hard and fast rule, and it would be a shame if there were. The English language is full of idiosyncrasies and new developments, and they only happen when people bend or break the established conventions. But spell-checking and predictive software prevent this: James Joyce surely would have given up on Ulysses had his typeface been marred by red squiggly lines. Shakespeare might not have invented the words ‘ladybird’ or ‘pedant’. When we hear so much about how young people’s jobs are being threatened by automation, surely it would make sense to discourage robotic writing, rather than make it mandatory.

Nameberry didn’t exist when my parents chose my name, an inexplicable mashup of Amelia and Emma – and possibly an unsatisfactory resolution to a marital dispute. I wonder if they would have chosen it if spell-check software had been as ubiquitous and insistent in 1994 as it is now. Probably not. My three siblings are named Freddie, Archie and Jack, so I think they would have gone with a conventional Emma. I’m glad they didn’t.

Emelia Hamilton-Russell is a writer for Spear’s