As teasers go, it wasn’t exactly subtle. On 24 January, just minutes after the closing bell on the New York stock exchange, Manhattan-based short-seller Hindenburg Research posted the tweet: ‘Soon we will release a report on what we strongly suspect to be the largest corporate fraud in history.’

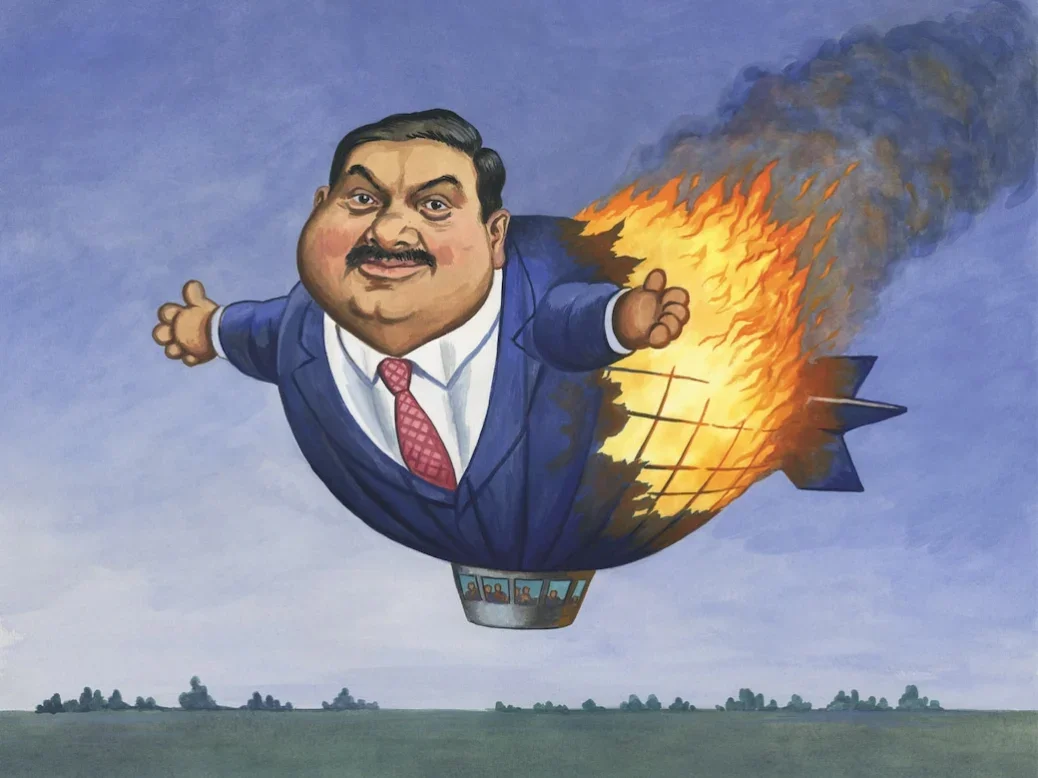

Anyone intrigued by the claim didn’t have to wait long. Just before 10pm that evening, Hindenburg played its hand, publishing a 30,000-word report which it claimed showed evidence of ‘brazen stock manipulation’ and ‘accounting fraud’ within the Adani Group: a powerful conglomerate controlled by India’s then richest man, Gautam Adani.

Soon we will release a report on what we strongly suspect to be the largest corporate fraud in history.

— Hindenburg Research (@HindenburgRes) January 24, 2023

As soon as markets opened in Asia, the impact of the report became visible. Stock prices for the various listed companies within the Adani Group – including India’s largest power generation company – lost their footing. Within days, valuations across the group had dropped by $100 billion: taking the Adani Group down to 60 per cent of its previous size.

At his office in Gujarat, 60-year-old Adani – a long-time ally of Indian prime minister Narendra Modi – was thrown into a campaign of firefighting. As the markets reeled, he was forced to battle a margin call on a $1.1 billion loan from a consortium of Western banks.

In a bid to stop the damage, Adani pledged a shake-up of corporate governance, as well as hiring one of New York’s most aggressive law firms to take the fight to Hindenburg.

But who was Hindenburg anyway? For those not acquainted with the world of short-selling, the group is probably best described as the corporate alter ego of Nate Anderson.

The 37-year-old chartered financial analyst is one of the more prominent examples of a new wave of activist short-sellers, self-styled muckrakers who look to expose evidence of corporate wrongdoing and then profit from the fallout.

What is short-selling?

In its basic form, the concept of ‘going short’ – ie betting against a stock – is as old as the market itself. Typically, an investor will borrow shares in a company they expect to fall in value, and then sell those shares on to a third party. If their hunch turns out to be correct, the investor can then buy back the shares at a lower price and return the loan – allowing them to pocket the difference.

Examples of legendary shorts are numerous. In 2001 American investor Jim Chanos successfully took a large position against the once invincible energy giant Enron – earning him the title ‘the Darth Vader of Wall Street’.

In 1992 George Soros gained notoriety with a dramatic bet against sterling – a trade that reportedly earned his hedge fund more than $1 billion.

The rise of activist short-sellers

In recent years, though, the game has shifted, as the seemingly unlimited potential of the internet – as a tool for forensic research, whistleblowing and easy publishing – has turbocharged a cottage industry of activist short-sellers.

Unlike the average hedge fund manager, these short-sellers aren’t looking merely to profit from a receding tide or an overpriced stock, but to drive down the price of an individual company as low as it will go – potentially to zero.

‘We are looking for companies who are hiding a catastrophic situation,’ says activist short-seller Gabriel Grego, founder of Manhattan hedge fund Quintessential Capital Management.

‘This isn’t about companies being overvalued. It’s about finding criminal mismanagement or fraudulent transactions that undermine a company’s whole public premise.’

Grego tells Spear’s that some of his previous targets have even ended up being jailed on the basis of information his fund has uncovered.

A modern investigation

Like Hindenburg, Quintessential is currently on the offensive. In January it published a report accusing FTSE-listed cybersecurity firm Darktrace of using fraudulent tactics to inflate its sales revenue ahead of its initial public offering in 2021.

‘We are of the opinion that Darktrace’s financial statements may not be relied upon,’ reads the introduction. (Darktrace, for its part, has denied the claims in the report.)

Technology tycoon Mike Lynch and wife sell £100m stake in Darktrace | This is Money https://t.co/CkOpDyXPbD

— Quintessential Capital Management (@QCMFunds) February 11, 2023

With its commitment to ‘show your working’, Quintessential’s report is typical of the activist genre. Among other things, the report uses evidence of deleted social media posts (recovered via an internet sleuthing tool) to back up one of its central allegations: that Darktrace used bogus marketing spend as a way of creating fake sales transactions.

Elsewhere, there are selfies of Grego outside an empty office in a primarily residential building in Monaco: potential proof, he claims, that Darktrace used shell companies to inflate its takings.

Following the paper trail

So who makes money from Quintessential’s work? Grego tells Spear’s that his clients resemble those of a typical hedge fund: namely family offices and HNWs.

Due to the highly sensitive nature of his work, though, clients remain in the dark about Grego’s positions until they are made public. ‘We have to think about every risk,’ he says. ‘For example, what’s to stop someone getting in ahead of us by opening up their own large short position?’

Like most short-sellers, Quintessential trades on its past record. But how does it find potential targets?

‘We get a lot of information from third-party analysts – both long and short,’ says Grego. ‘We also do a lot of proprietary screening, looking for holes in a balance sheet or the like.

‘Sometimes you will spot things in the press where a journalist has flagged something but might not have the resources that we have to follow it up.’

The Nikola scandal

From time to time, the activist short-sellers strike gold (or perhaps, given their position, a less salubrious substance).

In 2020, for example, Hindenburg’s profile exploded when it published a bombshell report on Nikola, a New York-listed company claiming to have developed a fully electric pick-up truck.

Through on-the-ground research, Hindenburg was able to show that the prototype truck seen driving in the company’s promotional video was actually being rolled down a hill by its own momentum – an explosive claim later admitted by the company.

Within two weeks of the Hindenburg report, Nikola’s founder, Trevor Milton, had resigned – with a 40 per cent hit to his company’s stock price.

Almost two years later, a Manhattan jury found Milton guilty of two counts of securities fraud (his sentence was delayed in January). Nikola’s stock price has fallen 93 per cent since the Hindenburg report. Anderson remains tight-lipped on how much money he pocketed from the trade.

Herbalife gaffe

For every successful short, though, there are examples of failure. Throughout much of the 2010s, legendary US hedge fund manager Bill Ackman tried to convince the market that California-based nutrition company Herbalife was a pyramid scheme – spending tens of millions of dollars in a public campaign against the company.

In 2018 Ackman was forced to terminate his position, with Herbalife’s share price having gained 85 per cent in four years.

This captures the inherent danger of short positions. With a conventional ‘long’ position, for example, an investor can only lose their initial stake – and that’s only in the unlikely event a stock hits zero.

For a short position, though, the losses are potentially limitless, as the company’s stock price can multiply over and again (although, in practice, the losses would be capped by the margin call).

Unsurprisingly, losses are coming: between 2019 and 2021, US investors lost $500 billion betting against the gravity-defying surge of big tech stocks.

‘Corporate sociopaths’

For activist short-sellers, there can be other drawbacks in the form of aggressive blowback from the companies they target. ‘We’ve had everything from hackers trying to get into our email servers to people sending death threats over social media,’ says Grego.

How does it feel to receive that kind of harassment? ‘Sadly I think that’s to be expected when you’re dealing with some of the people we have dealt with. They are what I would call corporate sociopaths.’

A more conventional approach is to invest heavily in corporate firepower to try to disprove the claims of short-sellers – and force them out of their positions. Indeed, in February the board of Darktrace announced it had hired auditor EY.

‘The board believes fully in the robustness of Darktrace’s financial processes and controls,’ commented its chair upon the announcement, adding that the independent review had been commissioned ‘as a sign of confidence’.

From time to time, companies targeted by short-sellers (notably the German stock fraud Wirecard) will seek to cast doubt on the sellers themselves, painting them as slippery operators merely posing as virtuous whistleblowers.

Yet equity investor Barry Norris, whose firm Argonaut Capital uses shorts as part of its mission to provide ‘uncorrelated’ returns to clients, tells Spear’s he has become dismissive of those claims.

‘You sometimes encounter people who will say, “Well, they would say that, wouldn’t they?” about short-sellers’ research,’ he says. ‘But the real question is why they’ve chosen that particular stock – out of literally millions of others – to criticise.’

Not only is their research of very high quality, he adds, but it is also more independent than the output from the typical investment bank, which is often institutionally biased towards going long.

A ‘naked’ short-selling ban

Institutional criticism of short-sellers, on the other hand, has been more focused. In 2008 the SEC banned the process of ‘naked’ short-selling, where investors sell stocks they don’t actually own yet.

After the Gamestop saga in 2021 (where a battle between retail traders and hedge funds triggered a ‘short squeeze’, where a stock price is inflated through short-sellers rushing to cover their position), the SEC pledged to revive its long-mooted plans to force investors to reveal more information on their short positions.

For analyst Ihor Dusaniwsky, whose analysis firm S3 provides institutional and HNW investors with detailed analysis on short positions across the market, tougher disclosure rules are unlikely to dent the appetite for going short.

‘I think most people in the industry would welcome more transparency,’ he says. Not least as information on shorts can be useful for all types of investors, he adds – even those who class themselves as long only.

Conversations with hedge fund managers, meanwhile, reveal the importance of going short. ‘We are primarily focused on the energy market, where you have a lot of highly overvalued companies,’ says Renaud Saleur, chief executive of the evocatively named Geneva-based hedge fund Anaconda.

The fund uses a combination of targeted long and short positions to differentiate between those companies that justify their lofty valuations and those that don’t.

Saleur tells Spear’s that one short position – against the FTSE-listed hydrogen company ITM Power – has already delivered an 80 per cent return, and that he expects more to follow.

‘You have companies in this market trading at more than 100 times their revenue,’ he says – thanks, in part, to a clamour for ESG-friendly stocks among investors who haven’t done their homework (or are hoping to sell to others who haven’t).

The future for Adani

Despite the stark difference in the market caps of ITM and Adani (at its peak ITM was valued at $5 billion, less than 2 per cent of the size of Adani), there are some parallels between the two companies.

Not only had Adani spent the pandemic era ramping up its investment in renewables, its companies were also trading at similarly dizzying ratios of more than 100 times their PE. So could the Indian giant go the same way?

Already there are ominous signs (at least for Adani). Since the publication of Hindenburg’s report, Moody’s has downgraded its outlook on several Adani companies.

Meanwhile, banks including Credit Suisse have stopped accepting the group’s bonds as collateral from their private banking clients. Across the financial world, at least some appear to be bracing themselves for a heavy landing.

For its part, Hindenburg continues to project its trademark confidence, issuing a challenge for Adani to make good on its threats to take it to court (‘we have a long list of documents we would demand in a legal discovery process,’ reads its latest statement).

Short-selling has never been for the faint-hearted – and this battle looks to be no exception.

Order your copy of The Spear’s 500 2023 here.