Alex Matchett wanders through worldly installations at the design gala, pondering over Utopia’s ever-moving horizon.

London is not Utopia and despite the city’s inaugural Design Biennale title you are not going to find anything pertaining to such inside the granite casing of Somerset House. However the 37 interpretations of ‘Utopia by Design’ create a wave of strivings and graspings that it is impossible not to get swept into.

Utopia remains firmly nowhere, the ever-moving horizon, the illusory space in the designer’s mind. The spaces here are in no way a set but they do pay homage to that. Some take the political entity of Utopia out of the frame, others use it as a keystone, but all empower the design agenda as a more suitable vehicle than pure policy. Brexit is more of a ripple now – although many spaces here have become receptacles of the initial splash.

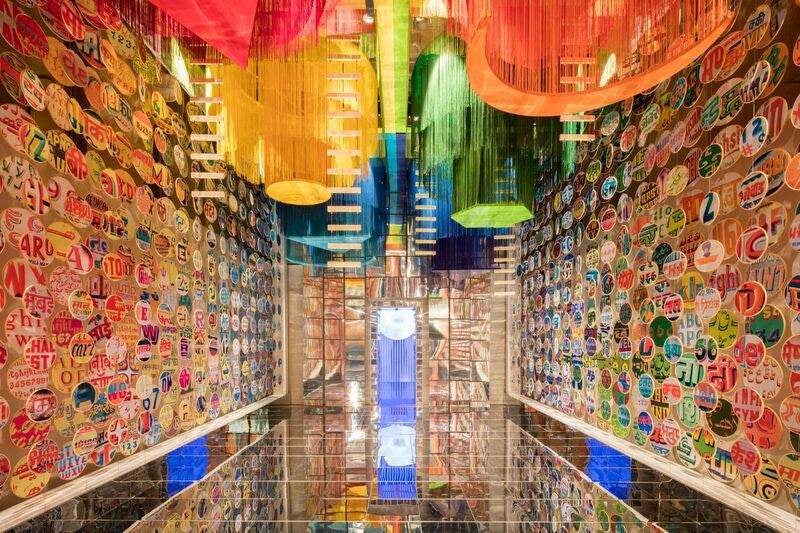

There are many highlights, including Lebanon’s street recreation Mezzing in Lebanon, India Design Forum’s ethereal cosmopolitan Chakraview (pictured top) and Poland’s irreverently post-modern Cadavre Exquis: an Anatomy of Utopia. However there are poor showings too: Sweden’s ‘Welcome to Weden’ attempts to show it is not Ikea by putting holes in furniture and designing an unfortunate yellow ‘we-we’ logo; Australia’s Plastic Effects is simply a table made of flotsam, a point well made but as unimaginative as its title; and Germany’s Utopia Means Elsewhere appears arrogantly banal.

At the press launch director Christopher Turner talks of the utopian design as now being detached from the social blueprints of the 20th century however there are showings of the importance of that heritage, notably in the display from Russia he rightly credits as ‘fantastic’. This space documents the ‘lost archives’ of the All-Soviet Institute of Technical Aesthetics (VNIITE). A project that ran from the 1960s until the fall of the Soviet Union, it aimed at realising utopian ideals in the everyday via a huge bureau of designers creating a holistic and functional vision. This is rendered on the walls of the display in blueprints and photos of prototypes of everything: from fire-engines to snow mobiles to hovercraft to phone boxes and bus stops. So much remained unrealised as the designs often exceeded production capability, but as the director Alexandra Sankova says, although this existed in a contrasting political and social paradigm the sense of innovation and inspiration is just as vivid.

‘All the people represented here design history and heritage and contemporary things but some things you have to rediscover,’ says Sankova. ‘The projects were ahead of the time, production was not ready to produce these things and also decision makers were not ready to appreciate these things.’

To see these designs now, in their first ever public display, and as they fade from living memory, is a privilege and welcome reminder that Russian design did not finish with the avant-garde and that the Soviet project existed far beyond totalitarianism and tractor factories. Sankova references the designers’ own heritage and the avant-garde movement a generation previously: ‘When they started they saw they needed something to be based on, and they were discovering their own history. That is what we’re doing now because without knowing your own history you cannot move ahead, and our history was interrupted so many times that we’re forgetting these sophisticated ideas. [There has been a post-Soviet sense of] “We don’t need it, we don’t need this old history, let’s throw it away and start again, we’re moving on.” We want to put together all parts of this puzzle and tell the history.’

The social design concept of that history exists in Mexico’s impressively futuristic ‘Border City’ project, designed by FR-EE and imagining a new metropolis on the Mexican USA border. Such international cooperation is also evident in Indonesia’s showing, a revisiting of the Africa-Asia Conference that ran from 1955 to 1965 and that is re-imagined here as the ‘Freedome’; a public satellite providing a global library. There are smaller, arguably more post-modern, addresses to Utopia here too. Turkey’s Wish Machine, designed by Autoban, invites you to watch your wishes fly around you in a tunnel made of vacuum tubes before disappearing into ‘infinity’, there’s a great sense of fun and childhood wonder akin to posting your letters up the chimney at Christmas time. Although my inner dystopian cynic can’t help thinking of how similar packages are posted through the Memory Hole inside Orwell’s Ministry of Truth and so into oblivion.

The packaging of memory and wishes is movingly seen in Benjamin Loyauté’s le bruit des bonbons — The Astounding Eyes of Syria installation for France. This features a short film interviewing Syrian émigrés talking about the objects they were able to bring with them and the food and sweets that remind them of home: small tokens of memory, the past and a lost country. Tiny objects that have bridged a chasm.

Adjacent are vending machines selling packets of small pink sweets modelled on an ancient Assyrian idol and named ‘Louloupti’. Each costs £5, the proceeds going to help Syrian refugee families. The project itself is a thought-provoking design journey, laden with emotional heritage as well as a ‘utopian vision’ to assist through small sugared snacks. These small cellophane-wrapped gestures are brilliantly designed story containers.

Journeys of abstraction are evident too in Austria’s display of stationary suspended lights (designed by Katharina Mischer and Thomas Traxler) which slowly dim and whorl when moved by those approaching, representing how Utopia is marred, and so invalidated, when touched; the arrogance of attainment rightly critiqued.

Outside in the courtyard sits the UK’s entry Forecast: Three massive wind masts. The inspiration is our national pastime – the weather. The designers, Edward Barber and Jay Osgerby, say it references utopian sustainable energy and a nautical, journeyed, past. But one can’t help thinking there’s a very British evasiveness here. It’s dark blue, perhaps a nod our maritime heritage but perhaps to somehow make it less present, to tone it down as if we’re embarrassed to be at our own party. Yes it’s huge and dominant, but, like the rain, we didn’t really ask for it, we didn’t actually want it, we just have this huge apparatus to help us talk about the weather, not actually deal with it. The real national pastime might be passive muddling shown by its indifferent rotating pieces, echoing the metronome of shipping forecasts, teaspoons stirring and batsmen changing ends. Message and media over any actual circumstantial policy. It’s a suitable navy blue elephant whose wind meter picks up a heady Brexit breeze and all the other hot air that brings a humid end to summer. They should put it outside parliament once the Biennale finishes.

Just behind this astutely forlorn gauge is Helidon Xhixha’s, sculpture Bliss (Albania). Known for his mirrored iceberg at the Venice Biennale last year, this piece has the same reflective make up but this time takes the shape of concentric brackets around a huddle of monoliths. ‘The piece is saying “don’t be worried of what is different. Embrace it”,’ says Xhixha through his translator and collaborator, Diego.

However, it has nothing to do with politics, he says: ‘It’s not judging the UK for initiating Brexit, but I do want to be an ambassador for making people think. Whatever you are going to do has consequences, not only now but in the future. It’s not about Brexit or political boundaries – there are common problems everyone has to solve, Europe is England, England is Europe. I need to talk to people in a very simplified way, no matter what language you speak, no matter what religion you follow or where you’re from, the message should be clear to everyone. When you sit here you understand you’re part of the agora of the world, when see your reflection you understand that one day you could be the immigrant coming from Syria.’ Xhixha also mentions his desire to have the piece placed outside, to reflect the past and present surmised in Somerset House, itself many sea changes of function.

Utopia now resembles a broken toy in the hands of politicians so we can be thankful that the theme of the London Biennale shows other forges in which to make our ambitions, be they abstract reflections or the industry of the practical. Technology is the engine of globalisation and this catalogue is nothing if not a reminder of that and the artistic mandate it inspires. With 37 different interpretations conclusion is elusive beyond blowing the dust of cliché from the concept and making it as perfectly unrealisable as ever. This inaugural London Design Biennale shows Utopia, and its wonderful uselessness, is a beginning and not an end.

The London Design Biennale is on at Somerset House until 27 September