An exhibition of British Concrete Poetry offers profundity and satire, writes Christopher Jackson

Concrete poetry? Let me explain. If you’re reading – you’re engaged in a literary experience. But you’re also having a visual one; all brought to you in the distinctive Spear’s font. If it were written in Japanese calligraphy it would be an artistic one too, and if I were to arrange matters so that this column ran down the page in the shape of a spear, I might be engaged in a bout of concrete poetry.

This exhibition, named after a work by the British concrete poet Bob Cobbing called Integration Alone Is Not Enough is in its last week at Richard Saltoun in the West End. Concrete poetry used to be a simple case – as it was for Rabelais – of producing a poem about a wine flagon in the shape of a wine flagon. But post-war concrete poets took the matter further by adding an audio aspect to their pictures: in modern times, this art form is a way of coming at reality from every angle possible. The idea is – to quote one of the founders of the genre, Eugen Gomringer (who isn’t represented here) – that a poem should be ‘a reality in itself’ rather than a statement about reality.

At its best – and we shall come on to Tom Edmonds and Kenelm Cox – concrete poetry can seem to do just that. But on this evidence it is often put to different use – either as wordplay, or as oblique philosophical statement.

For instance, in Henry Chopin’s Churchill = Church III = Eglise Malade (1964), we find the artist in punning mode, and perhaps a little too pleased with himself to have discovered that the word ‘church’ can be found in the word ‘Churchill’: Chopin appears to party with the observation that the ‘ill’ in Churchill can look like the Roman numeral ‘III’ – arranging the word church, along with its French translation église and, less explicably, the word ‘nice’ along the page. If ‘nice’ is meant ironically, then it might be taken as a cheery attack on the Churchill cult, but the work eventually meets the objection that there wasn’t really anything particularly churchy about Churchill.

Henri Chopin, Churchill = Church III = Eglise Malade, 1964, Dactylopoem on paper, 27 x 31 cm

On the other hand, concrete poetry in this vein can work well if the target is selected more judiciously, as in the same artist’s L’escalade, (1970/3); in this, the word ‘mort’ is arranged in the shape of an atomic bomb over the face of Richard Nixon. But even here it’s difficult to escape the simplicity of the conclusion: ‘Politicans = criminels.’ That’s a slogan, which is to say it’s the opposite of artistic enquiry.

Henri Chopin, L’escalade, 1970-3, Lithography, 58.6 x 46.7 cm

However, there are artists here who really do seem to deploy lettering along the page to yield up the essence of the thing they are claiming to describe. Tom Edmonds, for instance, succeeds with his 1968 dactylopoems on paper – all of them works of subtle beauty, with a kind of insistent meditation as their guiding impulse. One such poem is A Flight of Jays Squawk, Squawk (see below). Here, one can persuade oneself that something like the movement and rushing flutter of a group of birds has found its way onto paper. In Tribute to Vladimir Komarov Cosmonaut, even the catastrophe of an astronaut’s death is shown as a quiet dissolution, the marks on the paper, as peaceful as a firework exploding out of earshot in a nightsky.

Tom Edmonds, A Flight of Jays Squawk, Squawk, 1968, Dactylopoem on paper, 25.4 cm x 20.4 cm

Visitors to this exhibition are also invited to mourn the sculptor Kenelm Cox whose brass and wire piece Suncycle hangs discretely at the edge of the last room of the gallery: Cox was hit by a car in 1969 at the age of 41. This piece works by its heartfelt simplicity, and engenders a quiet awe about the solar round just by the dangled word of the title.

This exhibition will be followed later this year by a show devoted to the concrete poet Dom Sylvester Houédard, which will run between 26 May and 14 July. In that sense, this exhibition rather resembles one on the impressionists without Monet. But it also opens up onto huge questions: how language came to be, artistic genre, and even the problem of consciousness so that you return to the contention of Oxford Street suddenly, where one would least have expected to find it, at peace.

Integration Alone is Not Enough: Selected Works of British Concrete Poetry 1960-1980 ran at Richard Saltoun until March 24. Dom Sylvester Houédard: Typestracts will run also at Richard Saltoun between May 26 and July 14

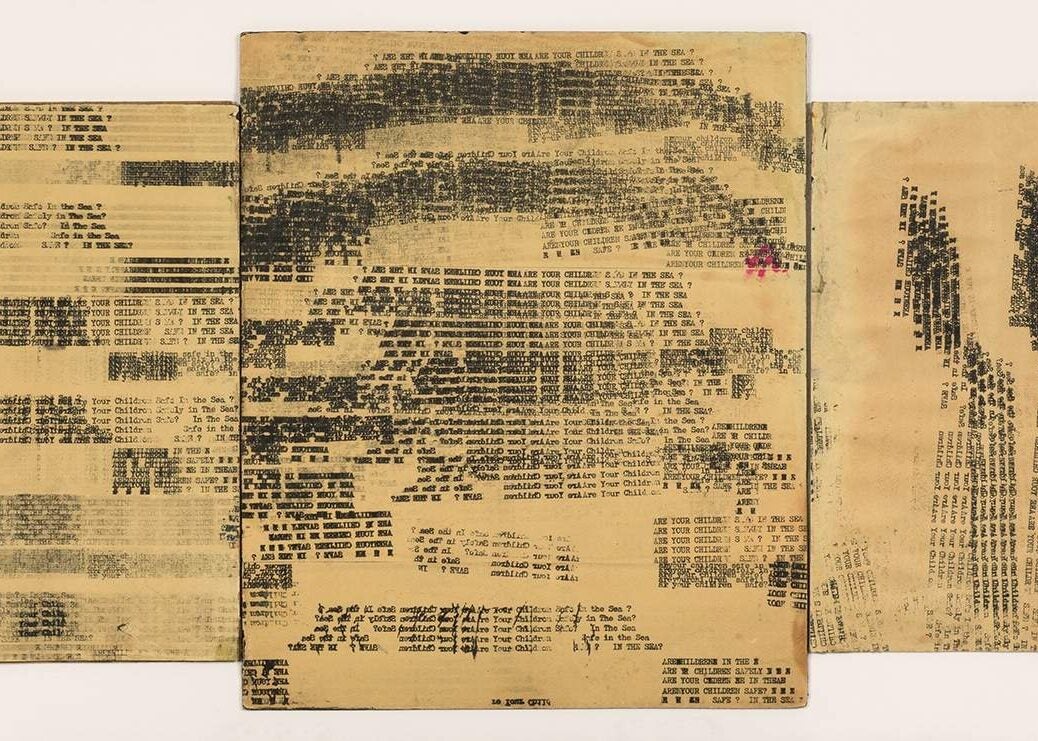

Top image: Bob Cobbing, Are Your Children Safe? In the Sea? 1964

All images in this article are Copyright the Estate of the Artist. Courtesy Richard Saltoun Gallery.