It took him 25 years, but in 2016 Nigel Farage achieved what he went into politics to do. Yet it keeps pulling him back in, he tells Alec Marsh

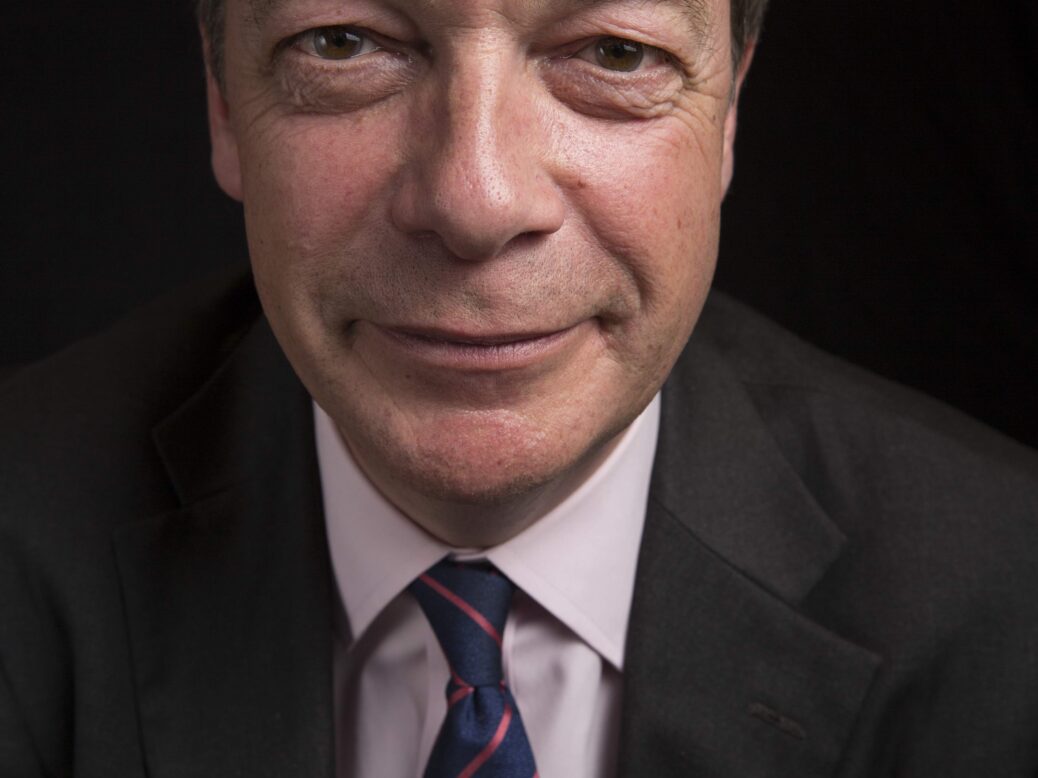

Nigel Farage arrives for lunch at Franco’s in Jermyn Street, and is smaller than I expected. With sloping shoulders, he is like the next-size-down Russian doll version of his enlarged media self. His face doesn’t quite look right, either. It takes me a moment to get there, but I’ve got it by the time we find our seats: his expression is restful, curiously passive.

Farage orders a gin and tonic as he accepts the menu from the waiter. I join him. Over the way, the ITN anchor Tom Bradby is having lunch, and Farage glances around the room, his eyes furtively eclipsed by those heavy lids. ‘Cheers,’ he says as we raise our drinks. ‘Nice to meet you.’

Farage knows Spear’s – a ‘very special publication’ – and its colourful editor-at-large, William Cash. Cash was once UKIP’s heritage spokesman, which put Farage – who led UKIP for a second time from 2010 to 2016 – in the unenviable position of being his boss. (‘If that’s possible,’ he quips.).

We order and, over a shared plate of Parma ham, settle into the topic. When did he first realise that Britain had to get out of the EU, I ask? ‘I was certainly on the Conservative Eurosceptic side of the argument from my late teens, really,’ he explains. ‘Certainly by the mid-Eighties, the Single European Act, I thought, “What a load of nonsense.” In those days I was a Conservative supporter who thought Mrs Thatcher was too Europhile!’ He laughs at that. ‘What really confirmed it for me is the Exchange Rate Mechanism. The whole idea was cretinous.’

Farage, 54, recalls that while all the major political parties, business groups, unions and newspapers endorsed the decision, he ‘started to rail against it – at every given opportunity, everywhere… I railed, predicting this would be a disaster, and sure enough it was.’

He also began attending meetings of the Bruges Group, the Eurosceptic think-tank founded in 1989, and of the Anti-Federalist League, set up by the LSE academic Alan Sked.

The Maastricht treaty of 1992 was the turning point: ‘That was when I thought, “Right, I’m going to have a go.” I told my friends and colleagues that even if it went nowhere, it didn’t matter. I would feel better in myself having made a stand.’ And stand he did: within months the Anti-Federalist League morphed into the UK Independence Party, and then in 1994 Farage stood in the Eastleigh by-election.

‘I was UKIP’s first candidate, I’d never stood for anything,’ recalls Farage, who came fourth with 952 votes. Twenty-one years later, at the 2015 general election, UKIP received 3.8 million votes, paving the way for David Cameron to deliver on his manifesto commitment to hold a referendum on future of British membership of the European Union.

‘You can forget Boris Johnson and Dominic Cummings, who were Johnnies-come-lately to the party,’ the commentator Simon Heffer tells me over email. ‘Nigel had been campaigning for a referendum for 25 years. It wouldn’t have happened without him and, because of his direct appeal to millions of people, it wouldn’t have been won without him.’

Farage acknowledges this with a decided lack of British self-deprecation: ‘It couldn’t have happened, could it?’ he crows, craning his tilting head towards me. ‘It wouldn’t have happened. The referendum would not have happened. That’s just where we are.’

Without you, I confirm? ‘Yeah, of course not. Impossible!’ As he grinds black pepper on to the Parma ham, I ask Farage for his political heroes. ‘I love Reagan – oh,’ he holds the note like he’s about to break out in song, ‘I love Ronnie. Wonderful. I like most of Thatcher – not all of it.’ (The bits he dislikes were her decision to ‘emasculate local government’ and the ‘betrayal’ of the miners.)

He also lauds Enoch Powell (‘on the European stuff ’) as well as the Eurosceptic Tony Benn – political godfather of Jeremy Corbyn. ‘It’s not necessarily a left-right thing for me,’ he says.

The After-Party

And now Farage is contemplating returning to frontline politics. Having walked away from UKIP last year over its latest leader’s decision to make the right-wing extremist Tommy Robinson a special adviser, Farage now has a new outfit, the Brexit Party. If Brexit is delayed after 29 March and the UK gets to vote on another set of MEPs in May, then he intends to run. He’s also limbering up for a second referendum, if it comes.

‘I can’t just walk away,’ he declares. ‘I can’t do that.’ He’s a vice-chairman of Leave Means Leave, a campaign group set up by former backers of Vote Leave and the Arron Banks-backed Leave.EU, which Farage fronted.

And he’s confident: ‘A second referendum becomes about different issues – it becomes about trust: here’s your chance to stick it to them. People will love that – a good old-fashioned AngloSaxon two fingers up. Absolutely.’ He roars: ‘Tell them again and this time in no uncertain terms. That’s why I’ve said if I have to do this again, next time no more Mr Nice Guy. Oh yeah. If they make us do this again they’re going to be in for a big surprise: a very big surprise.’

Instead of Theresa May’s ‘sell-out’ Brexit, Farage wants Britain to embrace the ‘hard’ alternative – ‘a genuine free trade arrangement, which is what parents thought they were joining 50 years ago’. ‘I’ve always said that a sensible free trade deal with our next-door neighbours made life easy. The only reason that I want WTO now is time has run out for everything else. So let’s just do it. Let’s deliver the promise. Let’s not believe the scaremongering rubbish.’

How come? ‘These things work themselves out,’ he breezes. ‘Money’s like water, it finds its level.’ And if Brexit doesn’t happen, we can expect trouble: ‘Now the threat we’ve got is how are the Brexiteers going to behave when Brexit gets betrayed, which it will do. And that is obviously a concern –’ he breaks off to order a glass of red. We end up taking a bottle, and he resumes: ‘One of my thoughts is, we have to make sure that there are vehicles that people who feel angry gravitate towards so that we can express this discontent in a democratic way and not a violent way.’

His view of what’s happened since the referendum is that we’ve seen ‘the victory of corporatism over capitalism’. ‘It’s the ownership of a political class by a handful almost of multinational businesses,’ says Farage, laughing, ‘that control the whole agenda. Without being conspiratorial, there is a big globalist bloc out there that actually want to run everything.’ And, as you would expect, it forms part of his critique of the EU – ‘the globalist government project’.

The EU ‘doesn’t believe in capitalism’, he says. ‘It doesn’t know what capitalism is! It believes in corporatism, which means you regulate, regulate, regulate as much as you possibly can. You strangle entrepreneurs in red tape. Because that means the big guys stay in business and the costs of entry to the market are too high. It is anti-capitalism, it is anti-competitive and actually it is why this gap between the rich and the poor has got wider and wider and wider.’ This all races towards me with intense conviction – it’s entertaining, captivating and might even have some truth to it.

‘This system doesn’t work,’ he continues. ‘And I would argue that in the Eighties, what we had was a form of engagement capitalism, both in Britain and America actually what you saw was the wealth gap narrowing, and you did, and social mobility was much higher, and I know which of those two models I prefer.’

For now the Farage fix is to get back to the nation state as the essential unit of political reality – what he regards as ‘normality’. ‘I’m always asked, “Are you a nationalist?” No. I’m nationist. I believe the nation state to be the right building block to do things – to cooperate with neighbours, and to make people feel they’re part of something. And nation state democracies which are functioning don’t fight each other – ever. And that’s an important point.’ Which is where the EU started. ‘And I get it,’ he replies, with more empathy than you might expect. ‘I’ve sat with Juncker and talked about it. I understand why Jean-Claude thinks what he thinks. I just think it was the antidote to a problem 50 years ago that doesn’t actually exist any more. It’s a solution to yesterday’s problem, not tomorrow’s problem.’

So let’s talk about tomorrow’s problem, I say: China’s ascendance. ‘It’s a big problem,’ he agrees. But not a rationale for the EU, to act as a counterbalance to an increasingly assertive Beijing? ‘Oh great,’ Farage fires back, his tone jovially mocking: ‘World War Three. Well done. Jolly good chaps. I know – there’s a big empire over there. Let’s build eight more dreadnoughts. Bloody terrific,’ he roars with laughter. ‘It’s a really scary argument that. It’s a scary argument.’

Europe’s decline

By 2030, he thinks ‘Europe as a place of importance will have diminished hugely in terms of power, wealth’. The euro is ‘finished, it’s dying, no one wants it’, so he’s clear: ‘The best thing to do is to be nimble, light on your feet, adaptable, and make the best of it. We’ll be in a much better position: back to being merchants – back to being traders. Back to being the players we’ve always been. It’s what we’re good at.’ Isn’t he worried about how we preserve our values on the global stage?

‘On a selfish basis we’ll do much better being flexible, adaptable and making our own decisions,’ he insists. ‘Of that I’ve no doubt.’ As for China’s challenge to the post-1945 world order, he is brutally realistic: ‘It’s time to move on.’ So how does the West maintain its influence? ‘We don’t,’ he says flatly. ‘We recognise that there is a massive transfer of people and wealth from West to East. It’s happening.’

How well is his friend Donald Trump doing on China? ‘His instincts are right on this. How effective he can be –’ Farage pauses. ‘It’s difficult. Generally on foreign policy Trump has done much better than anybody thought. This idea that he would be an isolationist president – he’s not been that by a long shot. Even talks with Kim Jong-un are preferable to not having talks with him.’ The US president, of course, is one of Farage’s more controversial international love-ins, along with Hungary’s authoritarian prime minister Viktor Orban. ‘A lot of things about Trump I like very much,’ Farage asserts. ‘Now, you know, his style, may be somewhat brusque – so what? On the really big stuff, Trump gets a lot right.’ And yet he’s derided as an ignoramus. ‘Just like Reagan,’ he says despairingly. A close parallel? ‘There are parallels in that sense: Reagan was a dunce, Reagan advertised Marlborough cigarettes and was in B-movies, unfit to lead America, and to the end the left hated him. He was never forgiven for a day, Reagan. Right to the end, and nor will Trump be.’

As for talk of Farage working for him, he discloses: ‘Oh, there were all sorts of conversations. Never going to happen. I’m a foreigner. I might not feel it when I’m there but I am, but I feel increasingly at home when I am there.’ Is Trump a thoughtful man, I ask? Farage ponders this before replying: ‘He listens more than people would realise.’

Which is also true for Farage, if our lunch is anything to go by. Does he realise Trump’s unpopularity in Britain has rubbed off on him?

‘Maybe a touch,’ he admits. ‘I knew at the time that it would have an effect, but I thought it was the right thing to do. Again you make decisions not based on short-term popularity but on what you think the right thing to do is. There is some truth in that. I could be completely wrong,’ he adds with emphasis, ‘but I think my support base amongst the British public is still there. I genuinely do.’

Tory Travails

We move on to British politics. He’s caustic about Theresa May – ‘this excuse for a prime minister’ – but does ‘admire her stickability… On a human level you’ve got to admire that.’ Who will be the next Conservative leader? ‘We’re probably going to get a Jeremy Hunt-type figure,’ Farage reckons. ‘He looks to me to be the top of the list by some margin. The Remainer who became a Leaver is a good story, and plays quite well in middle England. It doesn’t mean it’ll be him,’ he adds, ‘but it’ll be a Hunt type figure – somebody who comes from the middle, somebody who’s not a favourite. I know Boris desperately wants it, but I don’t see it.’ Is Johnson up to the job, I ask? ‘Oh, he’s up to it, in terms of the challenge, whether he’s the right person is for others to decide.’ This strikes me as an un-Farage-like comment. ‘It’s a funny one, really. In one way you think the moment has passed. Then for Churchill it looked like it had passed 20 times and he came back at moment of crisis.’ And we haven’t reached that crisis point yet? ‘We are building up to it.’

Looking across the Channel, Farage thinks Macron is finished – ‘the last great hope for the globalists and it’s all gone to dust’. He’s also ‘very bearish’ on Germany. ‘I just think that Germany has had its good times,’ he says. ‘Going to Germany 20 years ago, I was amazed how relaxed it was. How peaceful it was. How easy-going it was, how family orientated it was. It’s not a happy place now. She’s destroyed it.’

I know, like you, that he’s referring to Angela Merkel. ‘She’s destroyed those German cities through an immigration policy that’s insane. A terrible price to pay, I’m afraid.’ Farage is commenting on Merkel’s decision to open Germany’s borders to a million Middle Eastern refugees in 2015, a humane, brave decision that has been credited with fuelling the rise of the far right-wing Alternative for Deutschland party.

Is there a parallel with Tony Blair in 2004, when he gave free access to the UK to the new EU nations (when most members imposed immigration restrictions)?‘Yes and no,’ says Farage. ‘Yes in terms of numbers, but in terms of culture no. What we imported were lots of Roman Catholics.’ He chuckles. ‘It’s quite a big difference to what’s happened in Germany. That cultural distinction needs to be made. It’s tough to make it without being shouted down, but it’s true.’ I fall silent. ‘If you import a huge number of males aged between 18 and 30 who come from a country where women aren’t even second-class citizens, what do you expect? And that’s what’s been going on. So yes, I’m pessimistic for Germany.’

He believes more countries will join the likes of Italy and Hungary – whose leaders he clearly admires. ‘They want nation state control,’ he says. ‘I believe most of that should be healthy; there are circumstances in which it might not be healthy and I accept that too. Like anything, nationalism – or nationism, in its extreme form – would not be a good thing.’

The Haters

Outside, over a Rothmans, I ask Farage about hatred. It’s come up a few times during the conversation. ‘I remember when it first started it was a little bit of a shock,’ he says soberly. ‘I don’t think I was really under any illusions – I mean, I always knew that if it became a mass movement and very popular, then it was going to be very hard. I was under no real illusions about it,’ he repeats. ‘But it’s been,’ he finds his words, ‘yeah, I guess, it’s surprised me. The sheer extent of it has surprised me, but, yep.’

His voice trails away. The Farage bravura has suddenly vanished. I ask what it’s been like, dealing with the emotional antagonism. ‘Why do you think I go for a pint?’ he lifts his glass, and chuckles, but he’s not joking. A passer-by greets him and Farage breaks off cheerfully.

But then his sombre note resumes: ‘Some of it’s been horrible,’ he confides. ‘Some of it has been hard. And you almost feel like a wanted person at times. You’re surrounded by security – and he’s there now – in the car, he’s watching.’ Farage throws his gaze towards his waiting car. ‘There were times in the referendum when I had to be surrounded by people. It’s so rough out there. But I guess that’s the world we live in.’

Alec Marsh is editor of Spear’s

This interview will be published in issue 67 of Spear’s magazine, available on newstands from next week. Click here to subscribe

Related…

Interview: Lloyd Dorfman on UHNWs: ‘You don’t see a huge number giving’

Interview: Guy Hands, reign of Terra

Interview: Yanis Varoufakis on the end of Europe — and capitalism