After years of experimentation, Damian Elwes finally found his niche: re-creating the studios of great artists, writes Anthony Haden-Guest

It was meeting the graffiti artist Keith Haring that nailed it. Damian Elwes’s grandfather, Simon Elwes, was a society portrait painter; his father, Dominick, was a painter too, and when they died Damien inherited their brushes. This understandably put him off an art career, so he went to Harvard set on becoming a playwright. But then he moved to New York, set up a studio in an abandoned building on West 56th Street, and got a job doing crowd control on the 1984 Sidney Lumet movie Garbo Talks.

After clearing the crowd at one location, he found Haring drawing on the wall. Elwes, who had been astonished by the vitality of New York street graffiti, told him: ‘I’d rather be doing what you’re doing than what I’m doing.’ Could he draw, Haring asked? Yes. Could he paint? No. Haring told him about spray paint, $50 a box, and Elwes was soon making graffiti – not on the streets (‘I was too English’), but on the roof of his building.

Robert Fraser, the Mayfair gallerist, happened to be in New York, putting together a graffiti art show. ‘Somebody told him there was an English graffiti artist who painted a whole building on West 56th Street,’ Elwes says. ‘He said, “There’s no English graffiti artists.”’ But Fraser sent an assistant to check anyway. It wasn’t a timely moment. The management was locking up the building and putting up signs reading ‘KEEP OUT GRAFFITI ARTISTS’, so Elwes had to enter via a hotel next door.

‘I would buy a paper in the hotel lobby and the concierge would say, “Good morning, Mr Elwes! Your Herald Tribune.”’ Elwes would make his way to his studio via windows and two fire escapes. On this occasion the assistant clambered with him.

‘He said, “This is the coolest studio visit I have ever made. I don’t care what you’re painting, you’re in the show!” Luckily Robert loved the paintings and became my first dealer.’ So it was that Elwes first showed at the Fruitmarket Gallery in Edinburgh, with, among others, Haring and Jean-Michel Basquiat.

It was the start of an art journey marked by radical changes of direction. Elwes had decided to move on to painting on canvas, so he moved to Paris. Apprenticing himself to a senior artist was not an option, so he hit on another sort of self-schooling: painting artists in their studios.

‘I would walk down corridors and smell turpentine and linseed oil,’ he says. ‘Then I would knock on the door.’ These paintings of the making of art became a two-year project. Elwes returned to New York, where he got married, and then moved to the edge of the Colombian rainforest.

‘Out there I was doing huge paintings of forests,’ he says. When FARC, the revolutionary group, took an interest he decided it was time they moved on. They had been in Colombia for seven years. Elwes has two brothers in the movie business, both of whom live in Los Angeles, and it was there that the couple settled.

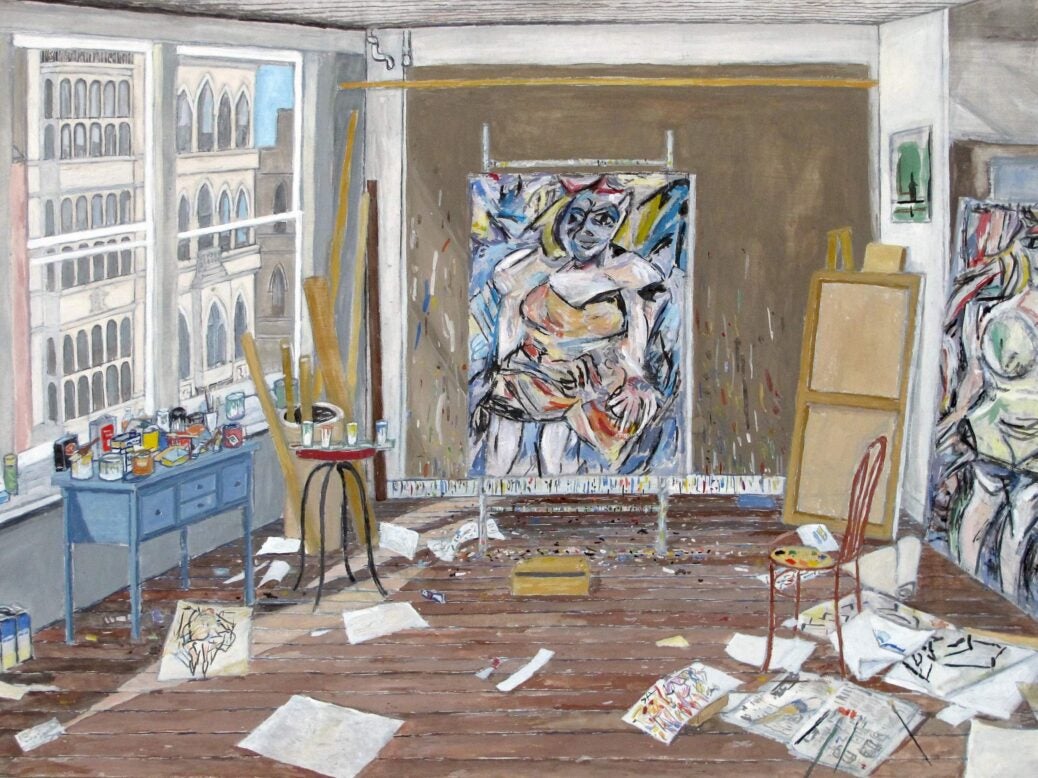

‘I wasn’t sure what I was going to paint,’ he says. ‘But the internet had just been invented. We didn’t have it in Colombia.’ His Paris experience came flooding back – with a difference. He would paint artists’ studios, where tremendous work had been created. And his first painting would be Picasso’s first studio in the Bateau-Lavoir. It would include Les Demoiselles d’Avignon.

‘When I bought a computer that was the first thing I started to Google,’ he says. ‘I found about seven existing photographs and I tried to put them together as a digital puzzle. I love puzzles. But there didn’t seem to be enough information to create the whole studio. Then I realised that the hand of one of the demoiselles on the right-hand side of the painting was in one of the photographs and the hand of the demoiselle on the left was in another photograph. So I had the whole studio. I painted the Bateau-Lavoir, Steve Wynn bought it.

‘Years went by, and another bit of information came up on the internet. It showed that maybe I had the stove in the wrong place. So I had to make another painting of the Bateau-Lavoir just to make sure I had it. Whatever place it was in I had got it.’

Elwes has now painted every Picasso studio; also the workplaces of Matisse, Miro, Giacometti, Francis Bacon, de Kooning.

‘It’s because I love painting so much,’ he says. ‘And because it’s in my blood. And because I’m a third-generation artist. Painting has been around since cave painting and it’s going to be around a long time from now. I had to take on these particular artists because they loom so large in my head that they can be overwhelming. It seems like almost everything has been touched on and done, and done incredibly well.’

A couple of years ago, though, Elwes wondered if he had taken this historical project far enough. ‘I was thinking I’d better do something really contemporary,’ he says.

Bingo! The Jeff Koons studio is the subject of one of his new paintings. ‘The first thing I do is listen to every available interview with Jeff Koons. He’s a very intelligent artist. What is the most meaningful breakthrough? It’s Balloon Dog. That’s such an amazing piece, it’s probably his best and also his best-known.

‘I found a photograph of him sitting on the original balloon dog before it had had the mirror surface put on to it. It was just a sculpture where the holes had been filled in, sometimes with blue, sometimes with red. And that’s what I wanted to paint. I’m interested in where it was in the middle, because we all know what the finished work looks like. Let’s see what’s going on in the process.’

Haring was another must. His former studio now houses the Haring Foundation, and Elwes made a discovery there. ‘There is still a lot of graffiti on the walls, and what I realised was that the graffiti wasn’t really graffiti. He would take his paintings when he had put down the colour black, or grey, or red. He flattened them against the wall and made a mirror image of the paintings on the wall. I’m not sure why. Maybe he wanted the paintings to dry really fast? Or flatten the paint?’

This led to a further discovery. ‘I suddenly realised that each bookshelf was a huge face looking at me. I could see the eyes, I could see the nose, I could see the teeth. And so I realised that he had made the bookshelves himself, or designed them. You didn’t see that immediately because they were so covered in stuff. I contacted them and said, “Did you save the bookshelves Keith Haring made?” And they said, “No, no, no! They were just a mess.” I said, “Well, actually they were Keith Haring sculptures.”’

He has, of course, made another Haring studio painting and says: ‘These are the things you discover while you are doing the paintings that make them really fun.’

Damian Elwes is on show at the Serena Morton Gallery, London W10 until late November. There will be a show of his work at the Musée en Herbe, 75001 Paris, from February to September 2018