It’s another good riddance to one of the last hard men of Africa, but we must be careful what we wish for, writes Alec Marsh

When is a coup not a coup? When it’s an allegedly bloodless transition of power in Zimbabwe, and one that could not have come soon enough.

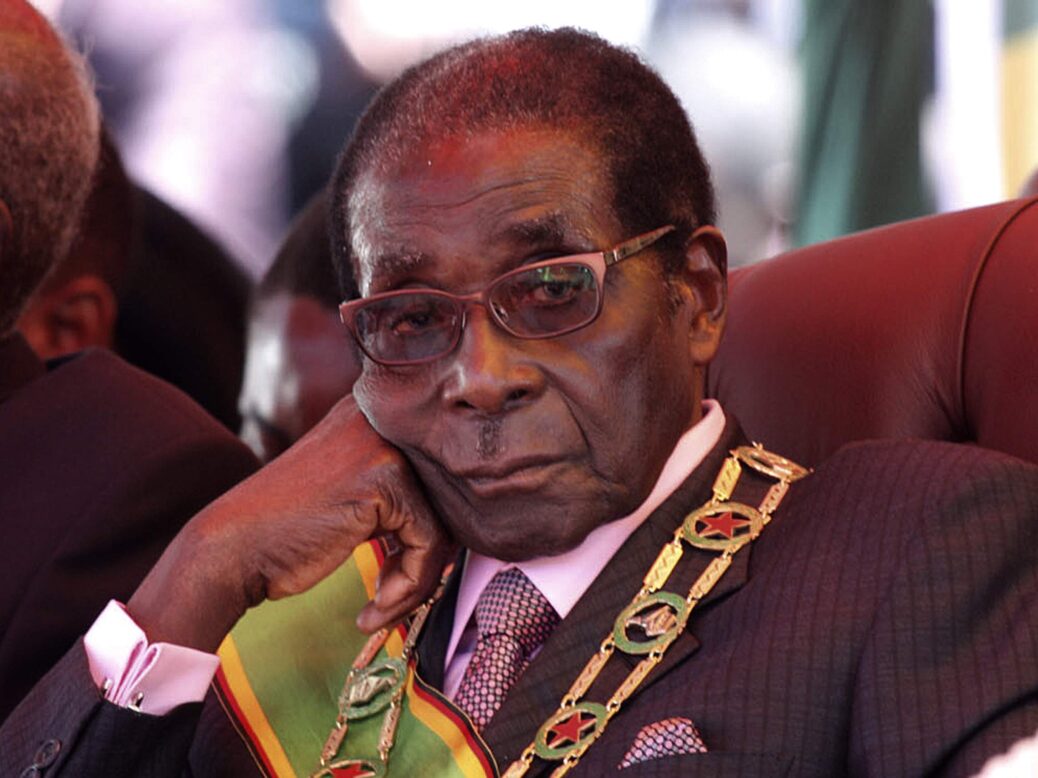

What is certain is that after 37 years, the necrotic rule of President Robert Mugabe, now 93, is over — in practice, if not entirely in name.

Whatever you think of its origins from the struggle of independence from colonial rule and its initial intentions, his rule has undoubtedly become corrupt, is widely believed to have been responsible for genocide in the 1980s, and has certainly economically bankrupted its country. Zimbabweans had more money in their pockets in dollar terms in 1982 than today. Inflation in Zimbabwe peaked in 2008, nudging an astonishing 80 billion per cent, before the country eventually stopped printing its own money several years later and moved over to a multi currency system based on the US dollar, South African rand, the Botswana pula, Australian dollar, Chinese renminbi and Indian rupee. Take your pick.

This had helped get hyperinflation under control, and since 2009, the economy has flourished, relatively speaking, recording several years of growth. Which of course Zimbabweans sorely needed after a decade of contraction (the IMF reports that this ‘raised poverty rates to more than 72 per cent, and left a fifth of the population in extreme poverty’.) Unemployment is now just under 10 per cent and the economy was forecast to grow 2 per cent this year, again according to the IMF, following two painful years of drought.

But that was not enough to stave off the end of the Mugabe era.

Overnight the army seized the offices of the national broadcaster and have secured other locations in the capital Harare. In a statement to the nation of 13 million and the world, a Zimbabwean army spokesman, Maj Gen SB Moyo, assured viewers that the President and his family were ‘safe and sound and that their security is guaranteed’. ‘This is not a military takeover,’ he said. ‘We are only targeting criminals around him who are causing social and economic suffering in the country in order to bring him to justice.’

Calling upon all the war veterans to play an ‘important role in peace, stability’ in the country, the officer followed the script of coup-makers by then cancelling all leave for military personal and ordering them to return to barracks. Finally, he asked the media, ‘to report fairly and responsibly’.

The military move followed Mugabe’s sacking last week of Emmerson Mnangagwa, his deputy and long-time ally — he served him as his assistant in the liberation war in 1977 and was a former intelligence chief — in favour of his wife, the First Lady Grace, who was reported to have fled the country. It has fuelled speculation that the military intervention is part of an internal conflict within the ruling Zanu-PF party to replace Mugabe with Mnangagwa. If this is the case, it may well have come as some have speculated with the backing of regional power South Africa, whence Mnangagwa fled after being sacked last week for ‘disloyalty’.

The BBC has reported that the South African President Jacob Zuma said he hoped events in Zimbabwe would not lead to ‘unconstitutional changes of government’.

The important thing for Zimbabwe is for calm to be kept, and then — who knows — perhaps it could be blessed with good governance. However the lessons of the Arab Spring (not to mention a certain transition that took place a hundred years ago this month in Russia) is to be careful what you wish for. Coups, governmental transitions — whichever expression suits your interests best — have unintended consequences and the West needs to do what it can to engage with whichever government that does emerge.

Alec Marsh is editor of Spear’s