You don’t need deckle edge books on your shelves to be glad that they exist. I fancy that Spear’s readers will, on the whole, number among those with the broadness of spirit to share that view

You always remember your first. For me, it was an American hardback of Ian Hamilton’s biography of Robert Lowell, lent to me in my teenage years by an attractive blonde girl called Clarissa. It had a matte paper dust wrapper in yellow with no photograph, which seemed very sophisticated. And, blimey, the pages were all weird.

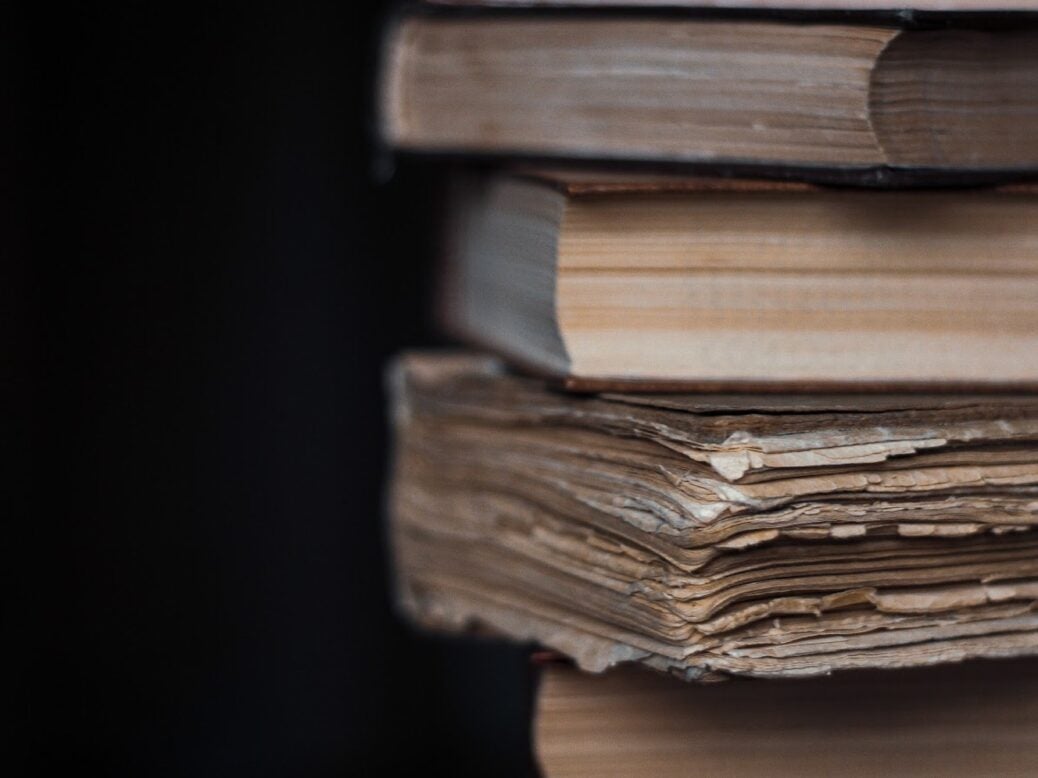

When the book was closed, rather than present a smooth face they zig-zagged in and out like the teeth of a comb. What devilry was this, I wondered. Now I know better. This was what US publishers call ‘rough front’ and others, including me, call ‘deckle edge’. It’s a way of mimicking how books used to look when paper was produced by squishing wood pulp flat in a press called a deckle (the rough edges were where the pulp squidged out of the side).

For much of the 20th century, after machining made those rough edges optional, they were nevertheless retained as a design choice to give books a bit of antiquarian distinction. Right up into the early noughties, big US publishing houses (it was always more of a US thing) would use this finish on literary fiction and prestigious historical non-fiction.

So I was shocked this week when I learned that Jeff Bezos may have done for this blameless quirk of publishing tradition.

I learned about it in a tweet from Random House’s infallibly shrewd copy chief Benjamin Dreyer: ‘It’s amazing,’ he wrote, ‘the way one retailer’s distaste for rough fronts (deckled edges, whatever, do people really call them that?) destroyed them so thoroughly it’s as if they never existed.’

What has happened, it turns out, is that ignorant Amazon customers had been returning deckle-edged books complaining they were defective, or leaving one-star reviews saying ‘pAgeS arE cUt Baddly’.

Instead of telling these eejits to go hang (because imagine how many one-star reviews they’d leave then, and the algorithm must be propitiated like a primitive god) the online retail monster instead started putting enormous trigger warnings on the listings several sizes the author’s name.

‘Deckle edge’, these warnings said, right next to the book title and in the same size font; which made the listings look clunky and ugly.

Then, apparently, if any edition of the same book – a large-print paperback, say – didn’t have the deckle edge it started showing up as the top search result, with the rough-front version lower down. Duly, publishers opted as one, pretty much, to discontinue deckle edges altogether.

Look, I know this may not seem like a huge deal to you. And, indeed, if I’m honest it’s not that big a deal to me either. I never really liked deckle edges. They always give you the faint sense that there may be a dried blob of egg yolk lurking in there somewhere, and it makes it that much harder to riffle pages smoothly in search of a quote. Books with deckle edges tend to look olde worlde, or American, or both.

But they are a part of the bibliographic ecosystem. I mean, I don’t hold much of a brief for crested grebes either. If I found one doing whatever a crested grebe does anywhere near me I’d probably be, like, ‘Yuk, get out of here grebe!’

But at the same time, when I read in the paper that the path of a new motorway threatens to eradicate the habitat of said grebe, leaving it – ha! – crestfallen, and that plucky protesters are chaining themselves to tree trunks to save the grebe, I’m rooting for the protesters.

You don’t need deckle edges on your shelves to be glad that they exist. I fancy that Spear’s readers will, on the whole, number among those with the broadness of spirit to share that view – not to mention including a few cultivated souls of a bibliophilic bent who will positively revel in the deckle edge.

The deckle edge, be it never so minority an interest, is a thing that gives the books of today a subtle but classy connection to the books of the past – those rough-edged signatures, those bare ruin’d quires – that your 18th-century gent would have gently cut with a paper-knife as he progressed through his book.

Its vanishing as if it had never been, we can count as a little victory for the forces of ignorance, and a small but telling step in the direction of an algo-directed publishing monoculture.

I’m told Mr Bezos and his minions have some unsound views on ‘French flaps’, too; but I think that’s probably something best left uninvestigated.

Photo by Olga Dudareva on Unsplash

More Sam Leith

Sam Leith: ‘Nothing you hear in middle age will feel to you like it could actually save your life’

How Homeland tracked the temper of our times