OOMPH! WHAM! KABLAMMO!

Lily in the pink cardigan is punching the air with gusto. Marjorie in the armchair next to me is barely tapping her feet, instead offering up pointed commentary on the action. In the middle of the room, Steve is singing along to Jailhouse Rock while showing the rest of the residents of the dementia floor at Sunnyview House in Leeds how to get their limbs moving: preferably punching forward, preferably in time, but any movement counts.

Steve works for Oomph!, a social enterprise having — exclamation mark notwithstanding — a serious impact on the care home sector. By providing trainers to 600 homes, Oomph! has so far given 100,000 hours of classes to Britain’s elderly, predominantly in the North but imminently elsewhere.

As we leave Sunnyview after 45 minutes of leg stretches, wrist rotations and pompom waving, all done to songs like Roll Out the Barrel and In the Mood, Steve tells me that these classes have physical and mental benefits, decreasing stiffness and sluggishness even as they increase confidence and happiness. By the end of the session, the ladies did indeed seem much more engaged, active and aware.

Read more on social investment from Spear’s

Oomph! is in many ways an excellent company to study: it started soon after Spear’s first looked at the social enterprise sector three years ago and it encapsulates three of the trends, with their attendant problems, which have swelled in the social investment market since. First, the definition of a social enterprise has become broad — or weak — enough to encompass companies who differ, sometimes controversially, from the classic type.

Second, the government has thrown its weight — fiscal and symbolic — behind the sector, most recently with a new tax relief. And third, big banks and other intermediaries have recently got in on the market, putting Goldman Sachs on the side, for once, of social benefit. All of these combine to start fulfilling the private-client promise of social investment: HNWs can put their money where their hearts (and brains) are.

Designer label

Like ‘bespoke’, ‘luxury’ and ‘family office’, as a desirable label ‘social enterprise’ has been adopted by more and more companies who might once not have been considered suitable.

For example, the SE100 Index, put together by a marketing company and sponsored by RBS, a bank desperate to prove its community-mindedness, says that four of the five biggest social enterprises in Britain are social housing association consortia, which one might otherwise think of as rather conventional businesses. Some of these don’t distribute profits but reinvest them, a social enterprise characteristic, whereas other modern social enterprises like Oomph! do distribute them.

Nick O’Donohoe, late of JP Morgan and now CEO of Big Society Capital, the social investment bank founded by the government to help investors access social enterprises (and vice versa), has a refreshing frankness when he talks about the sector. He agrees that ‘there’s a real question around fuzziness and definition’, which has in part led to current hype.

While a classic social enterprise — a charity or a community interest company (CIC) — is defined by ‘their broad social purpose but also by the fact they don’t allow for private gain’, he accepts that for-profit companies with ‘a very distinct social purpose’ fit here too. This muddying of the classes has its purpose: ‘The problem with [the first] type of social enterprise… is that you can’t raise equity into those vehicles, and if you can’t raise equity into vehicles, you constrain their ability to grow.’ (Growth is not, of course, the ultimate aim of all social enterprises, many of which are effective precisely because of their tighter purview.)

Joe Ludlow of Nesta, a charity which supports the most dynamic social entrepreneurs, tacitly acknowledges as much with his definition: ‘Do the activities, products and services delivered by this organisation intend to achieve a positive social and environmental good in the world? And is that the primary motivation of the company, its management, its shareholders?’ Talk of shareholders indicates the same argument as Nick O’Donohoe’s: with an asset lock, without equity capital and profit distribution, the enterprise may be ‘purer’ but it will also remain small.

Ben Allen, founder of Oomph!, is of exactly this view: ‘Asset locks are the wrong route for social enterprise. If you want to get great entrepreneurs and great staff in social enterprise, you need to be able to offer upside, otherwise we’re not going to attract the talent needed to roll social enterprise out nationally and internationally.’ And he should know: Nesta has invested £200,000 in Oomph!, in return for 15 per cent of the equity.

Energy supply

One of the chief challenges, says Joe Ludlow, is getting social investment in front of private clients, then energising them about it: putting the oomph behind Oomph!, you might say. Here, however, the government has been rather helpful.

When concerned groups met with the Treasury to discuss a potential tax relief (they dislike the word ‘lobby’), they went armed with evidence. Nesta’s research had established that there was an appetite among HNWs for social investments, once they were explained to them as different from standard investing and from philanthropy, and that the HNWs ‘identified the relevance of tax reliefs as a signifier of legitimacy’.

They spoke to IFAs, who said a tax relief would allow them to put it to their clients. And research commissioned by the City of London and Big Society Capital suggested that HNWs could put £480 million into social investment over five years. (For comparison, demand for social enterprise funding in 2015 alone is expected to be £500 million.)

Then, in December, George Osborne stood at the despatch box, said a few words and gave social investment one of its biggest boosts since Gordon Brown first put it on the political agenda in 2000. There is financial and symbolic importance in this move: yes, the government approves; yes, the government is going to make it more rewarding for you to get involved.

Now private bankers and wealth managers and accountants are much more likely to introduce their clients to social investment because, if we’re being honest, the social benefit has been embellished with even greater financial benefit.

The tax relief is not all that was desired; Nick O’Donohoe points out that it is capped at £280,000, as demanded by EU state aid rules, and is far less than EIS relief, which has been a model. Still, ‘The government have made a clear statement they intend to apply for exemption from EU state aid, but that will take a year or two. In the meantime we had a choice as to whether we want to go ahead with the relief and get it started with this quite low level, or do you want to wait? We felt we wanted to push ahead.’

The other issue is that you can only get relief on direct investments, although O’Donohoe is ‘absolutely convinced’ that there are plenty of HNWs who would lend up to £280,000 straight to social enterprises. It’s imperfect, then — but it exists.

Slick service

Back in Leeds, I can see why Nesta put some of its £14 million social innovation fund into Oomph! in January. Founder Ben Allen has a confident slickness, punctuating his conversation with business buzzwords like aggregation, infographs and stakeholders, but he also has ambition and steel. In his own words: ‘What we’ve got is quite a fun and interactive — what could be described as a “fluffy” — service, but with hard, quantifiable outcomes.’ He has a shelf-ful of awards too, including Shell LiveWIRE Young Entrepreneur of the Year 2012.

Nesta’s fund, supported by the Cabinet Office and one of several now available, is part of the final trend: the accelerating financialisation of social enterprise, that is, the development of intermediary organisations who will raise funds, arrange investment and funnel money where it can best be used. In short, social enterprise is starting to turn into a proper asset class.

If you want proof of that, you need look no further than the Vampire Squid: Goldman Sachs, whether because it has seen another money-making opportunity or because it wants to support positive projects or because of some mixture of the two, started to raise money for a $250 million social impact fund last November. In 2012, Goldmans also supported America’s first social impact bond, allowing adult-education programmes in a New York prison to be expanded. (Britain’s first SIB, by way of national boast, was launched in 2010.)

Apparently, social investment funds are like buses. In January, Threadneedle Investments made its UK Social Bond Fund available to retail and institutional investors, while last December Berenberg and LGT Venture Philanthropy closed their round. Threadneedle’s fund, in association with Big Issue Invest, ‘will invest in companies, associations, charities and trusts in social intensity areas’ from affordable housing to financial inclusion.

Showing how Big Society Capital has been making this market, it has given the fund £10 million, added to £5 million from Threadneedle, and it expects gross returns ‘in line with that of a UK corporate bond index… circa 4 per cent per annum’. Meanwhile, Berenberg’s, which is called Impact Ventures UK, raised £20 million and gives social entrepreneurs not just money but also strategic and mentoring support; investors get their own education programme.

PRODUCT PLACEMENT

Nick Jenkins, founder of greetings cards website Moonpig.com and serial angel investor, is a member of the investment committee of IVUK: ‘I was asked to join because of my experience of investing in and running businesses, but I took the role, which is

voluntary, so I could better see the range and quality of social enterprise investments available. When I sold Moonpig I used some of the proceeds to create an endowment for my charitable foundation; now I’m keen for that money to be invested where it can do something socially useful while maintaining a reasonable return.’

Product, widely reviled as the packaging of anonymous monstrosities during the financial crisis, is now key for ensuring social investment reaches the broadest — and wealthiest — audience. As Nick O’Donohoe says, wealth managers ‘will only really focus on it when there is a reasonable amount of available product. They’re not going to learn about something if they can’t put their clients’ money into it.’

Combined with the perceived legitimacy and the genuine inducement the tax relief offers, social investment will have more Lilys and Marjories up and down the country stretching along to an Elvis Presley megamix with every year that passes.

WHAT IS SOCIAL INVESTMENT

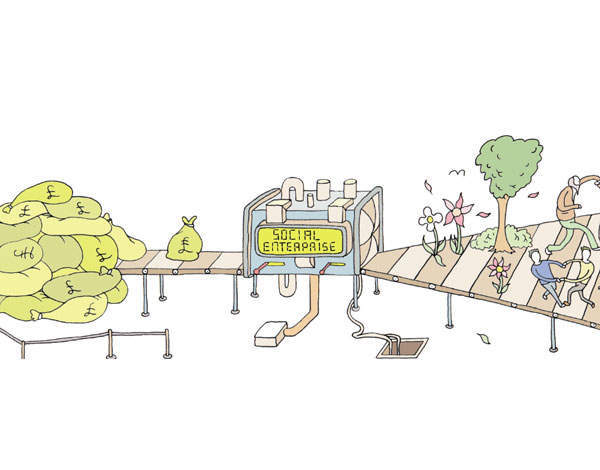

Social or impact investment, simply defined, is supporting social enterprises, businesses which have a double bottom line: financial and social or environmental returns.

With a social investment, the risk-return spectrum takes on a different tint. You also have to calibrate what kind of profits you want: is a minor financial return worth major social impact, or would you rather get back a heftier chunk of cash from a business which has hardly bettered anything?