Author: Stephen Hill

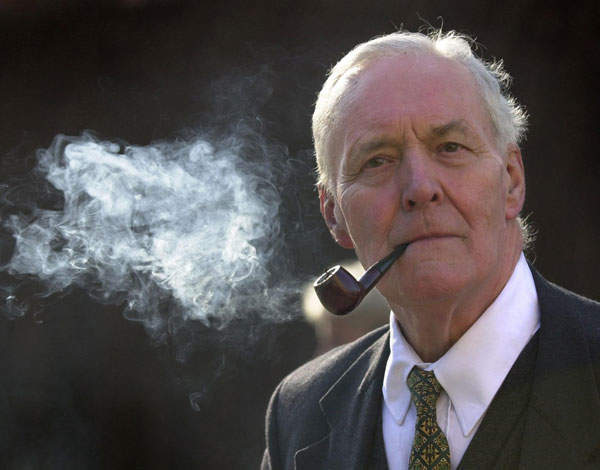

Bob Crow croaked last week and now Tony Benn has squawked his last too. The outpourings of grief and praise from the good and the not-so-great for these two wreckers of the UK economy were enough to make you puke.

Benn was the architect of Wilson’s White Heat of Technology revolution, which backfired badly. Benn the politician thought he could run industry, but wiser souls knew otherwise: when Benn went to the DTI in the 1960s, Sir Humphrey – a man called Carey – panicked and sent to the City for someone to ‘manage’ the situation.

A young man was despatched and told by Sir Humphrey to stop any viable projects reaching Benn’s desk. After a few months, Benn was reaching the point of frustration and called for all the projects in the department to be brought to him. ‘Now!’ exclaimed a gleeful Sir Humphrey, as he ordered the spigots to be opened up full blast and Benn was buried under a blast of projects.

Read more on the economy from Spear’s Stephen Hill

Benn then set up the grandly-named Industrial Re-organisation Corporation, the ill-fated IRC. He rubbed his hands with glee as he charged into the spiked guns of every failing industry he could find: shipbuilding, textiles, Leyland Motors, ball-bearings, coal, machine tools and so on, industries which were not destined to survive anyway.

The IRC failed to notch up a single successful re-organised industry, and was itself liquidated, with red faces all round. Politicians cannot run industry – or anything else, it seems – was the message. Benn thought he had found success with the Anglo-French Concorde, started in 1956, but its two constructors were the only two customers. Labour backed the wrong horse, as they closed down the vital TSR2 fighter, along with the Bluestreak missile.

Having wrecked the airframe industry, Benn was personally responsible for Britain’s biggest industrial disaster of all time: the 1971 receivership of Rolls-Royce. Determined to modernise British industry and to stick his nose into anything that smelled of a chance of success, he stepped in and personally ‘helped’ negotiate the biggest aero-engine deal of the decade, namely the RB 211 Trent engine development for the world’s first wide-body jet, the Lockheed L-1011.

Benn, however, was out-manoeuvred by Lockheed, who obtained a fixed price contract at a fixed exchange rate. When Old Labour’s polices, just like New Labour’s, caused a sterling crisis, Rolls-Royce declared bankruptcy as the only way out of Benn’s boomerang of a loss-making flat-earth contract.

Benn realised he wasn’t any good at industry, so started doing things he could do, like marching with a CND banner. I met him once at a book launch in Politicos twenty years ago, and we discussed the EU, on which subject he did wax lyrical, with insightful comments. He believed that at the heart of the EU there was a dark and evil centre which was anti-democratic, which was installing its own unelected bureaucracy to take over Europe.

Well, with Merkel as the new Charlemagne, Benn got this one about spot on. Last week, incidentally, I bumped into Lord Heseltine, who with a straight face maintained: ‘Of course Thatcher would have signed the Maastricht Treaty!’ I didn’t need to point out that the she couldn’t have, as he and others had already stabbed her in the back precisely because she wouldn’t have signed it. This is, I believe, what Benn meant by the anti-democratic, ruthless ‘evil’ at the heart of the EU.

Benn’s efforts to re-organise industry inevitably lead him to oppose the highly successful Thatcher privatisation process. But to his great credit, he was equally opposed to the invasions of Iraq, which like the IRC achieved precisely nothing, but at great cost.

Come to think of it, today’s New Labour looks increasingly like Wilsonian Benn’s Old Labour, as Ed Balls salivates at running everything from energy to banks to the NHS and raising taxes on the rich. Tony Benn’s son say he was a Benn, not a Bennite; Ed Balls is most definitely a Bennite.