Christopher Silvester on the chronicle of one woman’s life as a member of Chicago’s black elite, and Mark Le Fanu on the golden age of the English country house

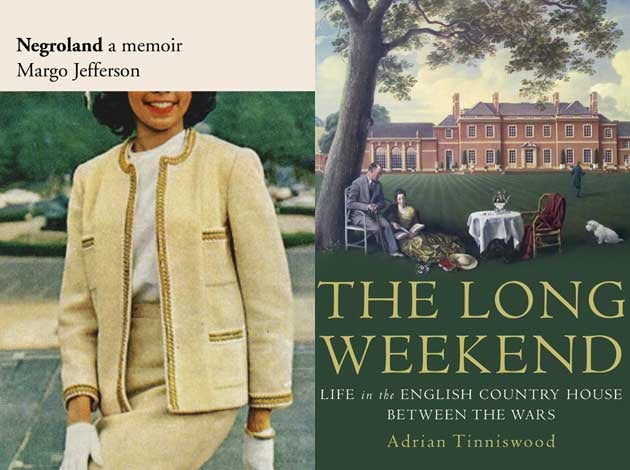

Negroland: a Memoir by Margo Jefferson

Margo Jefferson, a Pulitzer Prize-winning theatre critic for the New York Times, is a native of ‘Negroland’, which is her name for ‘a small region of Negro America where residents were sheltered by a certain amount of privilege and plenty’. She grew up thinking of herself as a Negro — that capital ‘N’ is important because it betokens dignity and self-validation. From having been slaves in the South, her ancestors progressed up the social ladder through respectable occupations until they became professionals.

Her father was a Chicago paediatrician and at one point the head of his department at Provident, America’s oldest black hospital; her mother was a socialite, as obsessed by etiquette as any upper-class white woman, only with the added patina of race. She once described their place in society thus: ‘We’re considered upper-class Negroes and upper-middle-class Americans. But most people would like to consider us Just More Negroes.’

Her father belonged to a fraternity, her mother to a sorority; both belonged to national clubs, his being the Boulé, hers the Northeasterners, as did their two daughters

(Jack and Jill; the Co-Ettes). But a couple of Margo’s white schoolfriends ask her ‘if we know their janitor, Mr Johnson. They think he lives near us.’

Jefferson’s family belong to a long tradition of Negroes for whom self-improvement is their religion: ‘the coloured elite’, ‘the coloured 400’, ‘the blue vein society’, ‘the Talented Tenth’. They carry a burden of responsibility as exemplars and role models.

At summer camp, Margo meets a Negro boy named Philip, several shades darker than her and with hair she knows to be bad ‘because it’s been shaved so close to his scalp’. She recalls that she not only looked down on him, but, worse still, she dreaded him. In a world of racial passing, hair type rather than skin colour is the giveaway. Therefore, it is no surprise to find Margo classifying hair into five types, the worst of which, ‘nappy’ hair, ‘requires heavier and heavier use of hair cream and constant hot comb use’.

The hair theme re-emerges in a comical anecdote from the 1970s when a Negro woman with straight hair finds herself taking off her Afro wig (worn as evidence of then-fashionable race consciousness) in front of a bathroom mirror in a nightclub alongside a woman with nappy hair who is removing her straight-haired wig.

Many Negroes have lighter skins, being descended from mulattoes, some of whom were the product of relations between a black slave mother and a white slaveholder father (which might also be the source of property and other inherited wealth). Dark skin, she writes, is best lightened as it ‘often suggests aggressive, indiscriminate sexual readiness. At the very least it calls instant attention to your race and can incite demeaning associations.’

When Margo watches television as a child — itself a mark of middle-class belonging in the 1950s — she is proud to see entertainers such as Sammy Davis Jr, Lena Horne, and Dorothy Dandridge, but her parents criticise Davis’s hair (‘too much oil’) while marvelling at his talent. Dorothy and Lena are both beauties, but Lena has ‘Cupid’s bow lips’ and ‘high, wide Indian cheekbones’ and ‘never has the lapses in taste Dorothy Dandridge has’.

Margo takes ballet lessons, though she lacks the talent and arch of her sister Denise; she reads Ebony, the magazine for Negro self-improvers; she attends one of the two Chicago private schools that take Negroes; her parents buy an apartment block in Hyde Park, living in one apartment and renting out the others to Negroes like themselves. When Uncle Lucious, who has spent his adult life passing as a white man, retires to Negroland, he is regarded as ‘a former white man’ and Margo’s parents look down on him: ‘Not because he’d passed, but because he’d risen no higher than travelling salesman. If you were going to take the trouble to be white, you were supposed to do better than you could have done as a Negro.’

Later, when Margo begins to suffer from depression, she confronts the ultimate taboo for

a Negro woman. Just as temper tantrums were off limits to Negro children, so the white female privilege ‘of freely yielding to depression, of flaunting neurosis as a mark of social and psychic complexity’, was ‘denied by our history of duty, obligation, and discipline’.

This beguiling memoir gives a fascinating insight into how one Negro woman negotiated the pitfalls of class and race from the 1940s to the ’90s, but it is equally valuable as social history (how so many early Negro achievers had been barbers, ‘knights of the razor’; the importance of Negro clubwomen). It is as funny about the nuances of class — its manifold embarrassments — as Alan Bennett’s A Life Like Other People’s. In short, it is a triumph of the memoir form.

The Long Weekend: Life in the English Country House between the Wars by Adrian Tinniswood

The English country house, and the way of life that goes with it, occupy a rather special place in our national culture, whether you are lucky enough to taste its pleasures at first hand or merely enjoy them vicariously, as millions do, through television series such as Downton Abbey.

The origin of its etiquette and protocols go back a long time – at least to the 17th century (if not earlier). Nor have its traditions entirely died out: the way of life it exemplifies still exists today, and even flourishes, if not on nearly so grand a scale as it did in its Edwardian heyday.

Adrian Tinniswood’s new book takes a detailed and appreciative look at the phenomenon as it manifested itself between the 20th century’s two major wars. One might have entertained the notion that the First World War was a watershed in this connection: after that catastrophe, nothing was the same again, surely?

There is a grain of truth in this. Many first and second sons had been killed on the battlefield, interfering with the whole system of inheritance. Meanwhile, new and heavy death duties were being imposed by successive governments, enforcing reluctant sales of property.

Servants, in addition, were becoming difficult to come by — at least, more difficult than heretofore: the First World War liberated working women in all sorts of ways and, other things being equal, there was no rush to return to domestic servitude.

Nonetheless — it is the thesis of the book — the country house and the unique way of life it exemplified enjoyed a sort of privileged Indian summer in the 21 years between 1918 and 1939. At the top end of the scale (for example, among the 26 non-royal ducal families that headed the British aristocracy), the wooing and capture of American heiresses which had begun in earnest back in the 1880s continued in the period under discussion. Quite a few noble fortunes, it is fair to say, were rescued and restored in this way.

If that didn’t work out, one could always sell a few acres: there were so many acres to sell! Tinniswood informs us that the Duke of Sutherland (one of the wealthiest men in the kingdom) divested himself of 329,000 acres of prime Highland deer-stalking land in a single year. Doubtless there was plenty still left over.

One of the things that comes across most forcibly in the book is the quite extraordinary number of houses, dotted around the countryside, that could be owned by single noble families. The Duke of Buccleuch, for example, possessed six, the same tally as that of the Earls of Wemyss — while the Duke of Northumberland had to make do with a mere five. Earl Fitzwilliam, we are told, ‘owned two estates near Doncaster, a Jacobean lodge on the outskirts of Malton, and two houses in County Wicklow in Ireland.’ Plus, ‘everyone’ had a town house in London. The Duke of Bedford had two — both of them, as it happens, in Belgrave Square.

So continuing wealth on quite a large scale was part of the explanation for the strength of the phenomenon. But there was also something more than this: a kind of antiquarian curiosity that broke out among the inter-war upper classes, and which took singular delight in the discovery and exploration of ancient ruins for their own sake.

Sissinghurst, in Kent, rescued by Harold Nicolson and Vita Sackville-West and planted with one of the world’s most beautiful gardens, is perhaps the classic example of such activity on a small scale. But Tinniswood is equally engaging and informative about other Kent castles in the neighbourhood, such as Allington, Bodiam, Hever and Leeds — all of which, under new ownership, were successfully adapting themselves during this period to the demands of the 20th century.

The energy and drive behind these conversions derived, in the first instance, from the new owners themselves: they were enthusiasts, determined to stamp their taste on their possessions. But they were fortunate in being backed by a section of the architectural profession who shared similar antiquarian passions.

Lutyens, inevitably, features in Tinniswood’s survey, even though (apart from glorious Castle Drogo) he had done most of his country house building by 1914. His influence continued, however, and is discernible in intriguing figures such as the dandy-architect Philip Tilden, responsible for designing the sumptuous mansion and swimming pool laid out by Sir Philip Sassoon at Port Lympne.

Tilden designed and built the house; the extravagant interior murals were executed by well-known artists of the time such as Rex Whistler, Glyn Philpot and José Maria Sert. ‘Interior decoration’, in general, was coming into its own in this period, led by prominent female arbiters of taste such as Syrie Maugham and Lady Sibyl Colefax, who owned shops in Mayfair.

Everywhere comfort was at a premium — for instance, it was the great age of bathrooms. With typical extravagance, William Randolph Hearst ordered 30 of them to be fitted for his ‘medieval fortress’ St Donat’s, overlooking the Bristol Channel. And everywhere there was an urge to make these rooms beautiful.

Interior decoration and gay sensibility traditionally go hand in hand. No social

history of England covering this period can avoid discussing homosexuality somewhere. Tinniswood has illuminating pages on the discreet lifestyle of prominent ‘bachelors’ such

as Noël Coward, Cecil Beaton, and Lord Berners. (Sassoon as well: one assumes this man was gay, like his famous cousin Siegfried, the poet.)

The dukes in their northern strongholds may not have ‘approved’ of such people but, with the exception of the unfortunate Earl of Beauchamp (‘outed’ by his brother-in-law

the Duke of Westminster, and subsequently sent into exile and disgrace by the King), on the whole tolerance reigned. That, too, is, or was, very English.

Tinniswood writes elegantly, in complete charge of his material. The book is a joy to hold in your hand. Jonathan Cape has done an excellent job in reproducing the text on high-quality paper with fine illustrations. Pretty good value at 25 quid, I should say. And very much recommended as a present to a friend or a loved one.