The Black Lives Matter movement has begun to send ripples through the world of wealth. What does that mean for the firms that serve HNW clients?

In 2018, Ricardo Peters, a black private banker based in Phoenix, Arizona, was ‘fired’ from his job at JP Morgan after he spoke out about alleged instances of racial discrimination at the bank.

A New York Times article entitled ‘This Is What Racism Sounds Like in the Banking Industry’ described how he was overlooked for promotion despite, at one point, having the best performance statistics in his state.

Peters also produced audio recordings of conversations with bank employees, including one where his supervisor rejected a black prospective client on the grounds that she would not ‘respect’ the money that she had been awarded in a wrongful death suit. JP Morgan said the supervisor did not know the woman’s race. He left his role at the bank soon after.

However, as Peters reflects now to Spear’s, the racism he encountered wasn’t always overt. He would notice that signs of unconscious bias – unintentional stereotypes about various social and identity groups – would permeate daily life at the bank. ‘Unconscious bias steps in from the minute you walk out of the street and into your job,’ he says.

This tallies with what Justin Onuekwusi has observed in his career. He now works in a team managing around £50 billion in his role as fund manager and head of retail multi-asset funds at Legal and General Investment Management. He is also a leading voice on diversity in the financial sector and was awarded the freedom of the City of London in recognition for his work promoting inclusivity. However, he recalls instances when people assumed he was someone else, such as a security guard or a tech assistant.

Because black people are not well represented in certain industries, they ‘just don’t apply’ for jobs in them, he tells Spear’s. Onuekwusi was once told by a black woman from a different firm who wanted to move into an investment role from her current position in operations, but said she would not apply if such a job came up in her office.

‘She would be the only black person on the floor, and she just wouldn’t want to do that to herself, given that she’s already one of a minority in the operations team,’ he recalls.

Issues of race and representation have come to the fore in other, more public-facing industries in recent years. In 2015 the #OscarsSoWhite campaign highlighted the fact that 86 per cent of top-grossing films had only white actors in lead roles. The movement generated discussion and some change. The number of acting jobs for women and people of colour is getting nearer to being proportional to the US’s overall population, according to UCLA’s Hollywood Diversity Report 2020.

So far, the world of wealth has not seen such a notable shift.

In London, where almost 70 per cent of the UK’s £7.7 trillion investment management industry is concentrated, 13 per cent of the population is black. But, according to a report last year, just 2 per cent of 3,755 investment management staff were from African or Caribbean backgrounds and just under 1 per cent of the 650 investment managers featured in that research identified as black, African, Caribbean or black British.

For a long time, this has been the status quo – from the wood-panelled world of Mayfair wealth management firms to the gleaming towers of international financial behemoths. But, recently, there have been visible signs that change may be on the horizon.

In May the killing of George Floyd at the hands of Minneapolis police officers sparked scores of protests in cities around the world. While some have objected to the nature of these protests – which have occasionally descended into violence and have resulted in the tearing down of statues worldwide – there can be no question that they have prompted broader discussions about the lack of racial equality in modern Western countries.

These, in turn, have sent ripples across the surface of the business world in an unprecedented way.

JP Morgan Chase CEO Jamie Dimon was photographed ‘taking a knee’ in front of a giant vault at a branch of Chase bank, to express solidarity with the movement, while Goldman Sachs CEO David Solomon committed to ‘help address the damage of generations of racism’.

Many private client and wealth management firms are expressing similar sentiments and taking action. One is the private bank Rothschild & Co, which runs several initiatives targeted at getting more black candidates to apply for jobs, including internships, graduate recruitment initiatives and apprenticeship schemes.

Clement Hutton-Mills, a London-based wealth manager at the firm, sits on an internal committee focused on promoting an inclusive working environment and attracting and retaining ethnic minority talent.

He tells Spear’s that the firm aims to reflect the diversity of its clientele in its client advisory team.

‘No two clients are the same, and you don’t necessarily have to put someone in front of the client who looks like them. It’s important to have a pool of people to draw from that can relate to clients on various levels – be that ethnic background, age or languages spoken,’ he says.

‘Our clients – and the lawyers, accountants, family offices, real estate professionals and other advisers that we work with – all expect us to take this seriously and have plans in place. So there is both a good social imperative, as well as a business need, that is driving this.’

Indeed, there is a growing body of research into the impact of diversity on business performance. In a report released in May, the consultancy firm McKinsey said that the case for inclusion and diversity in business was now ‘clearer than ever’.

Surveying more than 1,000 large companies across 15 countries, it found that companies in the top quartile for ethnic and cultural diversity outperformed companies in the fourth quartile by 36 per cent in profitability in 2019.

***

By contrast, companies owned by black people can often struggle to find funding. A report by the Federation of Small Businesses in June found that ethnic minority-owned businesses are ‘often detached from mainstream business support, and struggle disproportionately when it comes to accessing finance’, despite contributing around £25 billion to the UK economy.

In June, amid the most intense days of protest after George Floyd’s death, SoftBank – one of the world’s largest venture capital firms with total company assets of around £114 billion – launched a $100 million fund that would ‘only invest in companies led by founders and entrepreneurs of colour’.

As the firm noted when it launched this ‘Opportunity Growth Fund’, just 1 per cent of VC-backed founders are black. SoftBank has been joined by other VC firms such as Collab Capital, which launched a $50 million investment thesis targeted at black entrepreneurs.

For Eric Collins, a co-founder of VC firm Impact X, there is a ‘tangible differential’ that can be seen when backing companies with diverse teams.

Collins started Impact X in 2018 in collaboration with number of minority names from the VC world and related industries. The firm aims to support under-represented entrepreneurs across Europe, and is raising £100 million and amassed a portfolio of 17 companies.

‘As an investor and serial entrepreneur, the [disparity in] access to capital is very real,’ he says, citing a Kaufman study of 260,000 US start-up executives that found ‘perceived ethnicity’ had a large impact on fundraising.

Particularly striking is the finding that, despite this lack of access, diverse founding teams that do receive VC backing and make it to IPO or acquisition generate a median return of 3.26 times the sum invested – 30 per cent more than white founding teams.

‘The funny thing is that this information, though out there, seems not to have been reviewed, understood, deeply internalised,’ says Collins. ‘In some ways, Impact X should be almost obsolete. That’s the kind of information where you’d expect money to go flooding in.’ This, for him, represents the type of ‘market inefficiency’ that investors should acknowledge.

Social media messages and opening up conversations about race might be one thing, but Collins has a clear message for investors: They should ‘put their money where their mouth is.’

Indeed, the sort of changes he speaks about could yield a new, more diverse generation of clients for wealth management firms. But there is still much progress to be made.

***

George King, a senior wealth manager at Maseco Private Wealth, says that because the wider industry has little BAME representation among staff, it ‘isn’t even trying’ to talk to a diverse market. He is active in supporting ‘the minority wealth community, such as it is’. But, he adds, the industry ‘doesn’t have good networks for that’.

He recalls being approached at a recent event by a young black professional in her thirties who didn’t know how to get the information she needed about wealth management services. ‘There are no resources that this person can go to,’ he tells Spear’s.

Amaka Ogbonnah, founder of Amneo Wealth Management (now part of St James’s Place), agrees, telling Spear’s that many BAME prospective clients that she encountered ‘just weren’t being serviced’.

‘It doesn’t necessarily mean that they don’t have wealth management means, or that they don’t have the means to engage,’ she says. When Ogbonnah set up her own firm in 2018, she began networking within her community and found opportunities as a result.

She is a regular on panels and holds her own wealth management events aimed at women. As someone who has built networks, she has seen first-hand their importance when it comes to addressing challenges and supporting talent.

‘Being of the same background, we sort of go through the same experiences, and it’s nice to have the support of someone who understands what your journey has been like and what you’re going through,’ she says. ‘If you can see people who have gone through the journey, it is always nice to be able to tap into their knowledge and advice.’

On top of the evidence that supports investment in diverse companies, and the moral imperative to allow talented people to flourish, there are other risk factors that companies should take seriously, explains Kimberly Myers, CEO of All of Us, an employee engagement platform used by firms such as Mercer, Oberon Investments and CQS.

Companies that don’t make progress on issues of diversity and inclusion face ‘losing their employees, or not being able to attract to talent’, Myers says, noting that the up-and coming generations increasingly want their employer’s identity to reflect their own values and sense of self.

What’s more, companies could ‘lose clients’ and ‘damage their reputations’, says Myers. A case in point is Facebook, which in July faced an exodus of advertising clients amid concerns the platform was not doing enough to remove hateful content. ‘Companies are at risk of losing business if they don’t uphold the kind of values that are expected in 2020,’ she says.

***

But representation alone is not enough, says Albertha Charles, a financial services partner at PwC, who is also a member of the firm’s diversity council.

‘It’s important to have an environment where black people who walk through an organisation can feel that they belong and that they can thrive in a way that feels comfortable in their own skin,’ she says.

The necessity of ‘integration’ needs to be understood at the ‘top table’ of organisations: ‘If none of this is there, you just get organ rejection. They come in, they don’t belong, they feel marginalised sitting in the outer group and there isn’t a clear path and structural programme to ensure they succeed.’

Charles says significant progress on diversity and inclusion has been made at PwC in recent years. The firm reports its diversity pay gap and has made senior figures accountable for delivering on targets for gender and ethnicity representation.

Despite this, it was prompted by the Black Lives Matter movement to accelerate its work around ‘the “black” in BAME’. When it did, it discovered that black employees were progressing through the organisation more slowly than all other ethnic groups, and that staff retention was lower than average.

As a result, a ‘targeted campaign’ has been launched to ‘accelerate and sustain change around the experience of black people’. One measure will see senior managers provide career sponsorship to black junior members of staff, in order to expose them to ‘high-profile, career-enhancing jobs’.

Allyship – supporting marginalised groups in the workplace – can be an essential part of integration. Rothschild & Co’s Clement Hutton-Mills says that having black and white mentors has ‘helped me to get where I need to be’.

Of course, no wealth manager’s career can progress if they’re not delivering for clients, but ‘it’s also essential to have someone to speak for you when you’re not in the room’, he says. ‘We need to make sure that everyone becomes an ally.’

All the wealth managers, venture capitalists and financial services professionals that Spear’s spoke to for this article felt the Black Lives Matter movement and associated protests had created a unique moment.

But some worried the public and business community’s interest would fade – and that the column inches, social media posts and TV news reports would not yield real change.

‘What’s concerning me now is that there seems to be a level of fatigue around this,’ says Justin Onuekwusi, who has been a vocal advocate for greater diversity for more than five years. ‘And with that level of fatigue, people’s attention will move on.’

But there is also an encouraging precedent, says Maseco’s George King, who points to the example of the #MeToo movement against sexual harassment: ‘It started with noise and awareness, it started in a shift with what was tolerable.’

And the worldwide toppling of statues with links to the slave trade is an example of a step change that has been brought about by the Black Lives Matter movement, he notes.

‘You see this shift that is seeping into government and policy that is saying, “Actually you know what, this isn’t acceptable,” and you’re seeing actions from that,’ says King.

‘So there is some nascent sense that this could be an incremental tipping point. It won’t change everything, but it has the potential to really have some positive implications.’

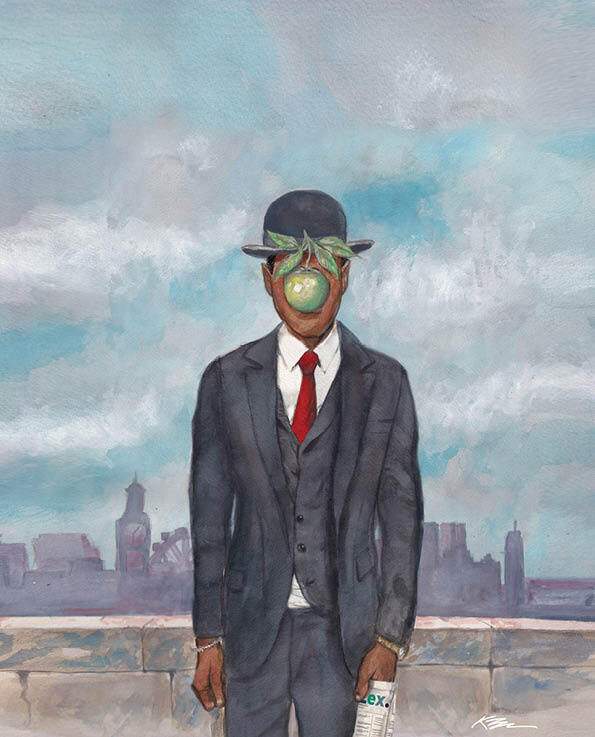

Illustration by Keith Henry Brown; Photography by David Harrison

This is the cover story from issue 76 of Spear’s magazine, out now. Click here to order a copy.

Previous Spear’s cover stories:

Cover Story: Is this the death of dividends?

Cover story: where will Covid-19 leave us in five years?

World exclusive interview: Prince Albert II of Monaco