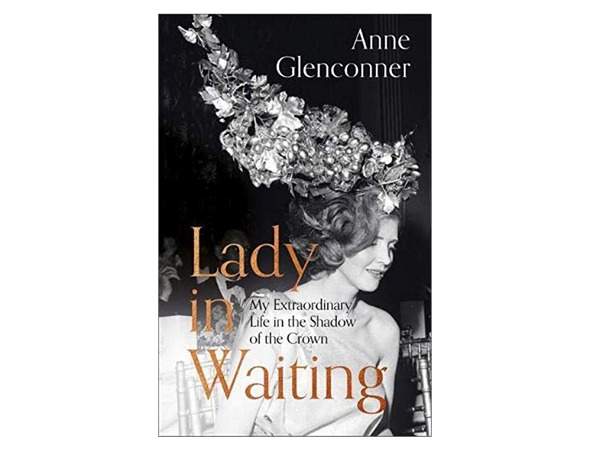

The memoirs of a close friend of the Queen and Princess Margaret shed new light on the era, writes Christopher Silvester

Anne Glenconner’s memoir is one of the publishing sensations of the moment, and deservedly so. As lady-in-waiting to Princess Margaret over three decades and wife to the eccentric Lord Glenconner, creator of the private island community of Mustique, you’d expect the 87-year-old to have some stories to tell, even while maintaining a veil of discretion over some things – but her memoir is teeming with anecotes and aperçus.

It is also an important contribution to social history.

One of three daughters born to the 5th Earl of Leicester, whose line was thus extinguished, Anne Glenconner grew up at Holkham Hall, her father’s ancestral seat in North Norfolk and the fifth largest landed estate in England. She enjoyed a playful and amusing youth, albeit one that was interrupted by evacuation to stay with a great-aunt in Scotland. ‘My childhood was a curious mix of carefree adventure in beautiful surroundings and a pressing fear of the war,’ she recalls.

The house at Holkham was so vast that ‘the footmen would put raw eggs in a bain-marie and take them from the kitchen to the nursery: by the time they arrived the eggs would be perfectly boiled’. There was one dark period of mental and physical abuse, when a governess called Miss Bonner would tie Anne’s hands to the back of the bed and leave her so tethered for the entire night. It left a permanent scar and years later, when Miss Bonner sent her a letter congratulating her on her engagement, she was physically sick at the memory it sparked.

Holkham was not far from Sandringham and the royal family. The princesses Elizabeth and Margaret came for summer holidays on the beach, where ‘we had a wonderful time, digging holes in the sand, hoping people would fall into them’. Later, when Anne was a teen, Prince Charles, 16 years her junior, spent several weeks at Holkham. ‘He would come to stay whenever he had any of the contagious childhood diseases, like chickenpox, because the Queen, having never gone to school had not been exposed to them.’ Anne was sent away to a girls’ boarding school in Essex and later to two finishing schools.

After a spell as a travelling saleswoman for her mother’s pottery business, she was named by Tatler as ‘debutante of the year’ in 1950 and embarked on the anxious search for a husband. A shortage of men, because those in her generation ‘had either died in the war or were still away doing National Service’, meant that ‘if you weren’t married by 21, you were on the shelf ’.

A shortage of money meant that dresses were made out of felt (unrationed) or, if you were lucky, dyed parachute silk. Coming out was a serious business beneath all the frivolity. ‘The Season was one huge rush of hormones and expectations binding the aristocracy together. While the aesthetics made it look innocent and romantic, the façade simply disguised the impending necessity to secure and heir for every titled family in England.’She was briefly engaged to Johnnie Althorp, who dumped her for the mother of the future Diana, Princess of Wales.

The reason, she learnt years later, was that she was rumoured to have Trefusis blood, ie mad or bad blood, from her grandmother Marion Trefusis. Such were the superstitious anxieties of aristocrats, even in the 1950s. The end of the engagement proved to be a stroke of good fortune, since it meant Anne could serve as a maid of honour at the coronation in 1953. She gives a rich and insightful account of this event, where she nearly fainted, had to be supported by a Second World War general and later took a swig of brandy from a hip flask provided by the Archbishop of Canterbury.

Then she met Colin Tennant. He was a member of ‘the Princess Margaret set’ and enjoyed nightclubbing. To Anne’s father, whose family had derived its fortune from the law and thereafter the land, the Tennants were beneath the salt, having made their money from the Industrial Revolution (bleaching powder). ‘Not only were they tradesmen, as far as my father was concerned, they were also nouveaux riches.’ Colin was even made to stand with the beaters instead of the guns at a Holkham Hall shoot.

Colin, who became the 3rd Baron Glenconner, is described as highly strung. Charming and charismatic, he was aware of his horrible bad temper, which once resulted in his being banned from British Airways over a dispute about seating arrangements. ‘Colin could be charming, angry, endearing, hilariously funny, manipulative, vulnerable, intelligent, spoilt, insightful and fun,’ she reflects.

Her only sliver of sex education was her mother’s reminder of what the family dogs sometimes got up to. Colin slept through their wedding night in a Paris hotel and the next evening took her to a private sex show where she was invited to participate, but declined.

On the Caribbean island of Mustique, which he bought in 1958, Colin was ‘ringmaster in Paradise’, inviting Princess Margaret on the one hand and Mick Jagger on the other, but he also inherited Glen, the family estate in Scotland, with its 50-room house. The marriage lasted 54 years, Colin sensing from the start that she would not give up on him. Her portrait of Princess Margaret is deeply affecting.

We have probably all known friends who are difficult in our lives. Princess Margaret was certainly that, but she was also a good friend, with a sense of humour and kind. As a house guest she would bring her own Marigold gloves and her own kettle (though she didn’t know how it worked!) and would insist on cleaning Anne’s car and, because she had been a Girl Guide, on laying all the fires.

There is tragedy here, too. Anne Glenconner buried two adult sons, one of whom died of Aids at the age of 29 and another of whom died of hepatitis C at 39. Another son lay in a coma for four months as a result of a motorbike accident.

His first utterance upon waking was: ‘Lamborghini.’ Lady Glenconner is an astute observer and has a breezily engaging style. She does not apologise for anything and there is nothing of the snob about her.

This book is a modest triumph and at the same time a triumph of modesty.

Read more

A walk through theatreland with Simon Callow

Interview: Salman Rushdie on Trump, Greta and eating the rich

Interview: Clive James on Dante, Brexit and Trump