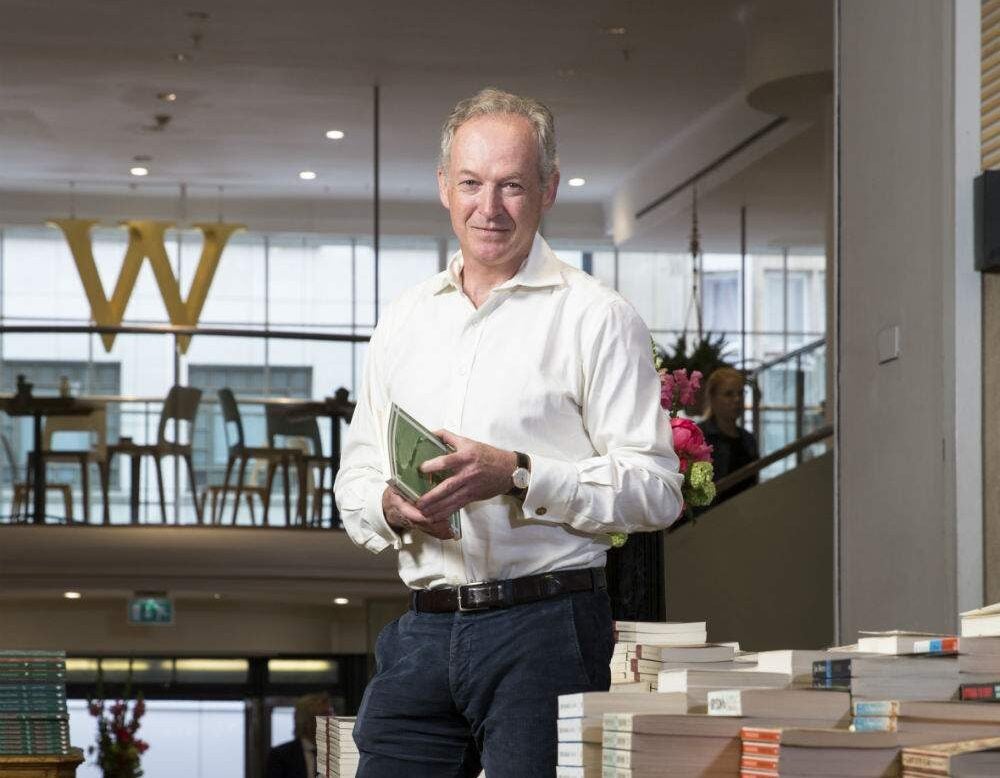

James Daunt arrived at Waterstones just as Amazon was about to wipe it out – and yet he turned the chain around. How did he do it, asks Christopher Jackson

The first thing I notice is his carefreeness: James Daunt bounds up the stairs two at a time and cheerfully orders coffee from the Waterstones café – as boyish a business leader as I’ve encountered. Like many successful people, he looks strangely healthy, a trait which is itself difficult to divorce from the sheen of happiness.

But if, as he steers our tray towards our table, he looks preternaturally content, he has reason to be. True, there’s been a lot of press about the recent purchase of Waterstones by the UK private equity arm of the US hedge fund Elliott Advisors. But Daunt remains the face of the British bookshop. In fact, he’s also an emblem of something rarer: a success story for the high street.

Daunt, the son of a diplomat, was educated at Sherborne before reading history at Cambridge. His career began in finance at JP Morgan. ‘There was a strong emphasis on values and internal culture. It taught me that morals matter,’ he recalls.

But Daunt was working long hours (‘My other half felt it wasn’t what she’d signed up for’) and, having always loved books and travel, he founded Daunt Books in 1990. You see the bags all over the city as a badge of the sophisticated reader: it now has six stores in London.

It’s an impressive achievement in itself. But the success of this venture now forms part of a larger narrative: Daunt was appointed MD of Waterstones in 2011 by Alexander Mamut, the billionaire Russian lawyer and investor. At that time, it looked like Amazon would sweep all before it. The scale of the inheritance is still vivid with him: ‘Waterstones did come within an absolute whisker of closing,’ Daunt says. ‘That’s extraordinary to think of. You’d be left with a few indies, but that would have deprived our main cities of a bookshop.’

But plainly Daunt, sitting here years later with Waterstones now turning an £18 million pre-tax profit (‘It’s not that much money,’ he says), did a lot of things right. So what did he change? ‘The way we bought books. Publishers who are now generally nice and appreciative found the change in buying very difficult.’

‘Nice’ is one of Daunt’s favourite words. It is also a fitting word to describe him – but he has been tough too. It was all a question of what the chain could guarantee to publishers. ‘If you pay £1 million to Jeffrey Archer for a book, it’s on the basis that it’s going to be around the country. But we were saying, “If you produce absolute garbage, we reserve the right not to carry it.”’

Daunt, 54, works with such calm logic that it’s easy to forget how much internal difficulty he had to surmount. ‘It was a strong culture, born of the [former owners] HMV and WH Smith mindset, and to my mind it was utterly bonkers,’ he says. ‘You were trying to run the same bookshop up and down the land; it was centralised. Coming in as an outsider, I thought, “How do you change that, and then change it without breaking it?”’

Daunt’s answer was to liberate his booksellers: they no longer had to wear uniforms, which he saw as a bequest of the ‘HMV Nazis’. He is also now fighting an internal battle for his staff to be paid on a salaried basis. ‘We pay everyone by the hour, which is how all retailers work. If you move to salary, you can get a mortgage – and I can then pay them more if I make it performance-related.’

Will his new private equity owners make such battles harder or easier? ‘We’ll see. They seem to be extremely rational investors, and if you apply common sense to this business you don’t change it much.’ And Paul Singer (the American founder of Elliott)? ‘Never met him.’

It is difficult to overstate the extent of Daunt’s power in the book world: what Waterstones buys affects publishers’ revenues, which in turn changes authors’ careers. Meanwhile, what his stores sell, and where, alters the public’s reading experiences. Imagine, for instance, if Waterstones were to decide not to stock the Man Booker Prize short list: end of Booker.

Daunt doesn’t use his power that way: his goal is to create an all-star team of booksellers and give them autonomy over the shop floor. It is a sort of business libertarianism. Daunt spells out its benefits: ‘As long as you leave the booksellers in peace, they will set up their shop really nicely.’ That word ‘nice’ again. Then he adds: ‘In an independent there’s a much more rigorous exercise of taste.’

That, of course, is the perennial complaint about Waterstones: that it has permitted, or even contributed to, a commercialisation of literature. But in respect of the firm’s returns policy – no publisher’s favourite aspect of the process – Christopher Hamilton-Emery of Salt Publishing puts it simply: ‘We never have a problem with Waterstones.’

Besides, Daunt would like to see more poetry and better books in our lives. ‘I just don’t think you can do it by diktat,’ he explains. ‘Within a chain, it’s been fascinating how changing simple things within the culture has been very slow.’

For some publishers that answer won’t quite be good enough: why use a top-down approach on moving the staff out of uniform, but not on the larger question of the overall health of our literature? According to Daunt this would be to underestimate the individual bookseller – a profession he obviously adores. ‘What I need is for my bookseller to want to do it,’ he says. ‘I came from an independent bookseller in a world of chains, and I loathed chain retailing. I needed to survive as an independent in a Waterstones world. And you rely on quality and creating shops customers want to be in.’

Those lessons were invaluable against that Dr Evil for certain lovers of the printed book, Jeff Bezos. ‘Effectively, we need people to walk past Amazon and behave the same way: you just have to make the shops nice. If there’s the right energy – most of it is about how you treat your staff so that they care what the shops look like.’

On the Kindle, Daunt is particularly enlightening: ‘My problem was: how do you stop your bookseller being scared of it? If every time someone walks in with a phone and you think, “Christ, are they going to take a photo and buy it off Amazon?” – that’s pernicious.’ Then comes the clinching argument. ‘Anyway, why are you frightened of Kindle any more than a library book? Libraries – those bastards make people read for free! Why do you love them? Because it’s all about reading. That’s what Kindle’s doing.’

Daunt is also evangelical about the bookshop experience: ‘One of the things we sell is the pleasure of walking out of a bookshop with a book – all those good intentions!’

He adds: ‘A book bought from a good bookshop is a better book than one bought in a supermarket under crappy sodium lighting.’

Of course, there are glitzy sides to the job – the Hillary Clinton signing last year (‘she shook hands with everyone in the building’), the hope of Michelle Obama this year. But really, meeting Daunt is an education in how simple business can be, if a good – or if you prefer, nice – man is prepared to let others thrive at what they’re good at.

James Daunt will be among the speakers at the Spear’s Wealth Insight Forum on 27 September at One Great George Street. See more at wif.spearswms.com