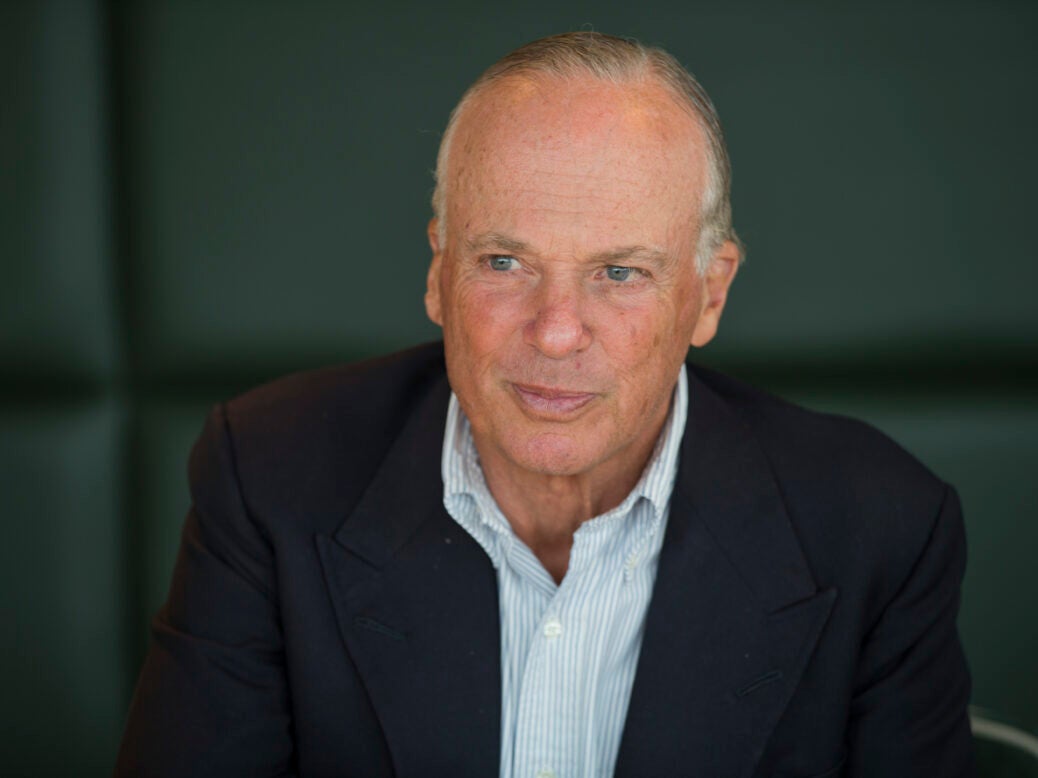

Michel de Carvalho has graced the silver screen, competed in the Olympics, and is married to a billionaire heiress – yet still goes to work as a wealth manager. Why?

Michel de Carvalho, chairman of private wealth manager Capital Generation Partners, is wearing a casual shirt under a zipped jumper. He looks like a man on holiday. Visible in the background on our Zoom call are the wooden beams of what I discover is his home in St Moritz; an exotic mural halos his head.

He kicks off in upbeat fashion: ‘I’ve just recovered from Covid,’ he declares. ‘So I’m very, very happy. It’s great!’ He and his wife Charlene de Carvalho-Heineken, the billionaire owner of a 25 per cent controlling stake in the famous Dutch beer company, caught the virus when they went to Dubai by private jet (which they thought would be safer) from Zurich.

‘We all took PCR tests before each flight… and we got it from one of the crew,’ he explains. They are both through it, but passed it to their cook and ski-guide – not that that’s an issue. ‘They’re all thrilled because they feel that they’re now immune,’ adds de Carvalho.

In childhood Michel de Carvalho, son of a Brazilian diplomat, became a movie star and acted opposite Peter O’Toole and Omar Sharif in Lawrence of Arabia in 1962 when he was in his late teens.

But then he dropped acting and went to Harvard, only to postpone his academic career when he ‘fell in to the British Olympic skiing team’. His parents weren’t amused: ‘I got cut off but luckily from the film money I had enough to survive on,’ he says.

He went on to compete at three Winter Games in 1968, 1972 and 1976. He returned to Harvard and became an investment banker, rising to vice president of Citi Investment Bank and chairman of Citi Private Bank. But that was all before de Carvalho was invited by managing partner of CapGen, Khaled Said, to become its chairman.

‘My only condition of joining was that I would never have any financial remuneration from CapGen,’ de Carvalho says. The job does come with perks, however. ‘I’m very grateful to have a car park underneath Berkeley Square, right opposite Annabel’s, and an office.’

Besides, he says, as he approached the end of his two-decade tenure at Citi, he needed somewhere ‘to put’ his PA.

Carvalho was appointed chairman of CapGen in 2018 and appears to have loved every minute. He tells me of his joy of getting up at 5am to fly to Malta with Saïd to take part in a 17-firm beauty parade for a major prospective client. ‘That’s not the sort of thing that most people do at my age,’ he says, ‘I found it unbelievably exciting.’ (They won, too.) ‘It’s a wonderful atmosphere,’ he says of the firm. ‘No client has ever left CapGen, that’s quite a record.

When Carvalho was at Citi he tells me he was adamant about not ‘opening his address book’ to the bank or mixing his private and professional lives. ‘If you’re an investment banker it doesn’t help,’ he explains. ‘You’re dealing with CEOs of companies, you’re dealing with the Ministry of Finance in Sweden… it doesn’t help to swan in and say, “Did you know my wife is a multi-billionaire?”’

Yet as unpaid ambassador-in-chief for CapGen he must be worth his weight in gold. His family is now ‘the second biggest client of CapGen, having built that up over eight or nine years’, which is a significant endorsement.

In a world often populated with grey suits and institutional twaddle, de Carvalho is a straight-talking cruise missile of charisma. And then, of course, he’s an Olympian.

‘I bring the same competitive nature whether I’m standing at a start gate of a ski race, or a golf course, or in business – whether it’s Heineken or CapGen,’ he says. I ask if being a UHNW himself gives him a special ability to advise wealthy clients – of which CapGen has 22, along with $3 billion in AuM – and clearly it does.

But he begins his answer by explaining some of the financial arrangements of his own family, the Heinekens. The family office in Amsterdam has money with five banks or wealth managers, including CapGen, of course, and Goldman, Citi and JP Morgan.

Under his initiative, the family office produces a monthly financial report, accounted in euros and put together by an external consolidator, which details all the holdings at each institution. This is then shared between them so that each knows what the other is doing.

‘At the end of every month we can see the performance by each of the banks we work with, netted out for foreign exchange,’ he explains. ‘If we were in the office I would show you the report because that’s something I’m quite proud of having created,’ de Carvalho says, adding another gem: ‘We really make sure all the bankers, rather than the banks we deal with, behave as if they work in our family office.’

He also mentions an instruction that is given to all their financial partners: ‘Assume that every time you make a recommendation, we say “yes”.’ I wonder if, as someone at the top of the wealth pyramid (the Sunday Times Rich List ranks him and his wife in ninth place, with their fortune thought to be north of £12 billion – the couple’s wealth grew by £1.7 billion last year), he’s observed a change in society’s attitude to wealth and wealthy people? He says he hasn’t but is quick to explain that he and his wife have a low-key lifestyle (‘She and I drive Volkswagens’).

They only take private jets Dubai notwithstanding, when they’re dashing to Holland and back for Heineken board meetings. ‘If you didn’t know either of us you would just see two reasonably normal, successful people enjoying a pleasant non-flashy lifestyle,’ he says.

And it’s clear he believes that the way UHNWs live, invest and behave – manners are important to him – matter both in their own right, but also in public perception.

‘What I see amongst people with large amounts of money is a greater consciousness about the world around them,’ he adds, making a segue into ESG investing, which he sees as ‘very much part of CapGen’s DNA’.

‘I’m glad to say it’s become part of the DNA of Heineken as well,’ he adds, concluding: ‘We talk about it now. In another five or 10 years’ time if you started talking about it people would just look at you and say, “Why are you talking about it? It’s natural.”’

***

After an hour of chatting, I ask him why he gave up his career in film for a life in a suit and tie.

‘You’ve asked me the one question I was hoping you wouldn’t ask,’ he says. ‘It’s puzzled me my entire life.’ But then he tells me why: shooting Lawrence of Arabia, aged 17, he spent nine months in the Jordanian desert living under canvas with a tutor to get him through his exams.

‘If you and I watched the film together, I could show you the scene where I walk through the door of some blown up tent,’ he says. ‘As I walked through the door I suddenly said to myself – “What on earth am I doing here?”’

Where were his friends, why wasn’t he out playing football? What was he doing hanging around a bunch of ‘not very normal people’, the sort who ‘need an audience when they wake up in the morning to tell them how well they’re brushing their teeth’?

So he packed it in.

Decades later he says he would ‘love nothing more than to have a cameo role in a film now’. I laugh and assure him that if I meet a producer looking for an active 80-year old I’ll mention him.

‘Steady on,’ he shoots back – and I suddenly wonder if I’ve dropped an age-related clanger.

‘Are you 80?’ I ask. ‘This is the end of the interview,’ he says, with a smile. I’m laughing but apologise as he moves on to explain that a man has three ages – the one stamped on his passport (1944 is his year of birth, he says), his biological age (what shape he is in) and finally his mental age.

‘You blend the three together and divide by three and you come up with your actual age. So I’m about 47,’ he states. ‘Massively helped by my mental age.’

I’m laughing again as he continues to protest: ‘No one has ever asked whether I was 80! Do I look like I’m 80?’ He certainly doesn’t.

But fortunately we move onto another topic. If I take away one thing from the interview, he suggests it should be that ‘what you see and what you hear with me is what you get. That’s the way I talk to my family, talk to my friends. People always tell me that it’s quite dangerous for me to talk to journalists because I just tell them the way I am, so I hope that came across.’

Loud and clear, Michel. But then, if anyone has got half a brain – let along half a billion to invest – then they know that this is a valuable trait. The truth will out, and the sooner you hear it the better.

The interview concludes with an invitation to join him for lunch – when conditions permit. I’m looking forward to it already. As I said, he’s a cruise missile of charisma.

More wealth management coverage from Spear’s

Go East: Singapore’s family office boom

The 2021 Spear’s Wealth Management Index