There is nothing quite like a superyacht.

Sparta, one of the winners in 2024’s International Superyacht Society Awards, features a glass lift, an infinity pool and a gym in addition to its lavish living quarters. The idea of creating a home on the sea certainly has historic appeal. And yet, to launch a vessel of such value on to an element as unpredictable as water is not without risk, as recent tragedies have shown.

The ancient philosophers viewed such endeavours as man’s ultimate challenge of nature. One of the oldest Greek myths highlighted the dangers of underestimating the opponent and trusting too much in mortal skill.

Icarus soared to the sky, only to tumble to his death when the sun melted the wax of his hand-crafted wings. His father Daedalus had warned him not to fly too high. Many other myths explored what could happen when one approached the sea without due caution.

Homer’s Odyssey most famously told of how one man took an entire decade to cross the waters on his journey home from Troy. Odysseus endured repeated setbacks and shipwrecks as monsters and gods punished him for his perceived hubris.

[See also: Is the world’s first hydrogen-powered megayacht the future of yachting?]

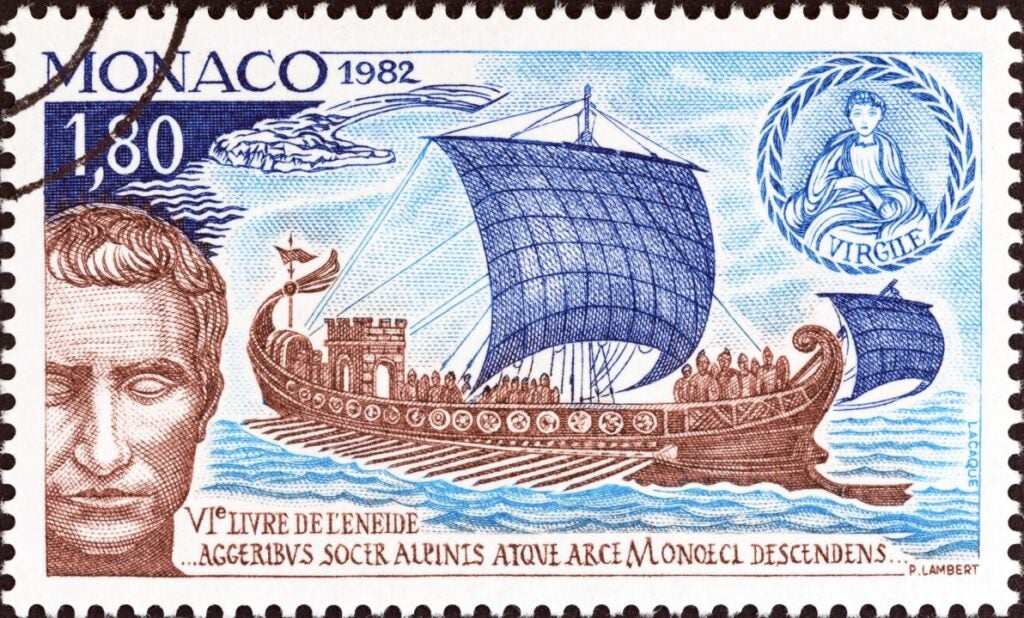

Fear of opprobrium and death did not stop the real Greeks and Romans building vessels that would help them traverse the world. Leaving aviation to Icarus and the birds, they poured their strength into boat-building and endeavoured to steer clear of the depths by hugging the land as much as possible as they passed between continents.

Sailing as a glamorous activity

Trade was the priority, but as early as the Bronze Age there are signs that sailing could also be a glamorous activity. The Minoans, a pre-Greek people who inhabited Crete in the third and second millennia BC, possessed boats with awnings and bell-like decorations dangling from bow to mast.

Ancient history suggests that there is, deeply ingrained within us, a fascination with inhabiting the water which trumps all fear of the unknown. To build boats which resemble homes and send them out to sea is an attempt to colonise what can never truly be ours. The sea belongs to everyone but also to no one. It is everything that a plot of land is not. Swirling, churning, rising, falling, it is as inhospitable a playground for mankind as can be, but still the temptation to conquer it remains.

Superyachts astonish because they give the impression of achieving the impossible and turning runaway water into stable, claimable land. This is why some of the most powerful people in history have sought solace on their decks.

It is, as they know, divine to walk on water.

Cleopatra, who associated herself with the goddess Isis, took Julius Caesar on a pleasure cruise down the Nile and welcomed his cousin Mark Antony aboard a magnificent barge with golden stern, silver oars and purple sails. Caesar’s descendant Caligula, who thought himself a god, took the concept of the superyacht to unprecedented heights.

The Roman emperor grew infamous for his excessive spending and extravagant appetites. In a demonstration of power, he commissioned galleys with jewel-bedecked sterns, baths, dining rooms, porticoes and gardens with vines and fruit trees. There would be no fancier setting for his depraved orgies.

The ancient historians’ details of Caligula’s pleasure boats defied belief until the remains of two galleys with parts inscribed with his name were recovered from the seabed at Nemi near Naples in the 1920s.

[See also: Best yacht advisers]

Although much had decayed, it was clear that the boats were terrifically grand, each extending to more than 70 metres in length, making them twice the size of Athenian triremes (warships). They had marble walls and columns, mosaics, piston pumps and pipes for warming the baths. Few Romans of the first century would have experienced anything like this before.

There are rumours that a third ship is still down there waiting to be rediscovered.

Such is the hope, for what nature preserved, man destroyed; the salvaged boats were catastrophically consumed by fire following a shelling in the Second World War. What a hollow victory it was for man in his eternal tussle with nature.

This feature first appeared in Spear’s Magazine Issue 94. Click here to subscribe