Amid the widening retreat from internationalist ideals, here’s an idea for anyone wishing to make a low-key, yet eloquent, statement of global-mindedness: fasten a worldtime watch (or ‘worldtimer’) to your wrist.

These show the hour in 24 time zones – represented by city names encircling the dial – all at once, via a rotating 24-hour ring whose indications line up with the cities, while central hands give you the local time wherever you may be.

Born in the Art Deco era, and often seen with maps or other travel-associated illustrations rendered in miniaturised form in the central dial, it’s a concept of supreme ingenuity, elegance and charm – and it’s having a moment.

Jaeger-LeCoultre, for instance, has brought out an achingly fine world-time version of the Reverso this year, which gives you the local time on one side (the Reverso being its famous ‘flippable’ watch), and the 24 time zones on the other.

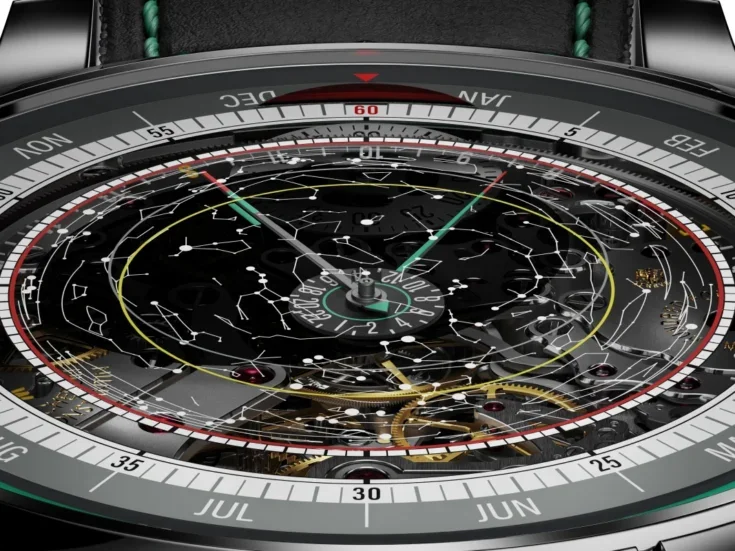

Bovet has done two impressive worldtimers in two years; and in April, Andersen Genève, a tiny haute horlogerie atelier whose classical worldtimers have long been adored by collectors in the know, launched its latest exquisite take, the Communication 45.

More than 90 years on since its invention by watchmaker Louis Cottier, the worldtimer feels now, more than ever, like the most modern of salutes to a cosmopolitan mode de vie; a suave affirmation for a global citizen.

[See also: Square watches are cornering the market]

On the other hand, it will hardly get you thrown out of Mar-a-Lago, since it can be quite the status symbol too.

Being finicky things to make, somewhat niche in style, frequently a canvas for traditional decorative crafts and, by definition, targeted at what we used to call the jet set, worldtimers tend to be the preserve of top-tier luxury makers.

Besides those mentioned above, Vacheron Constantin, Ulysse Nardin and award-winning indie Voutilainen are among those currently producing rarefied examples.

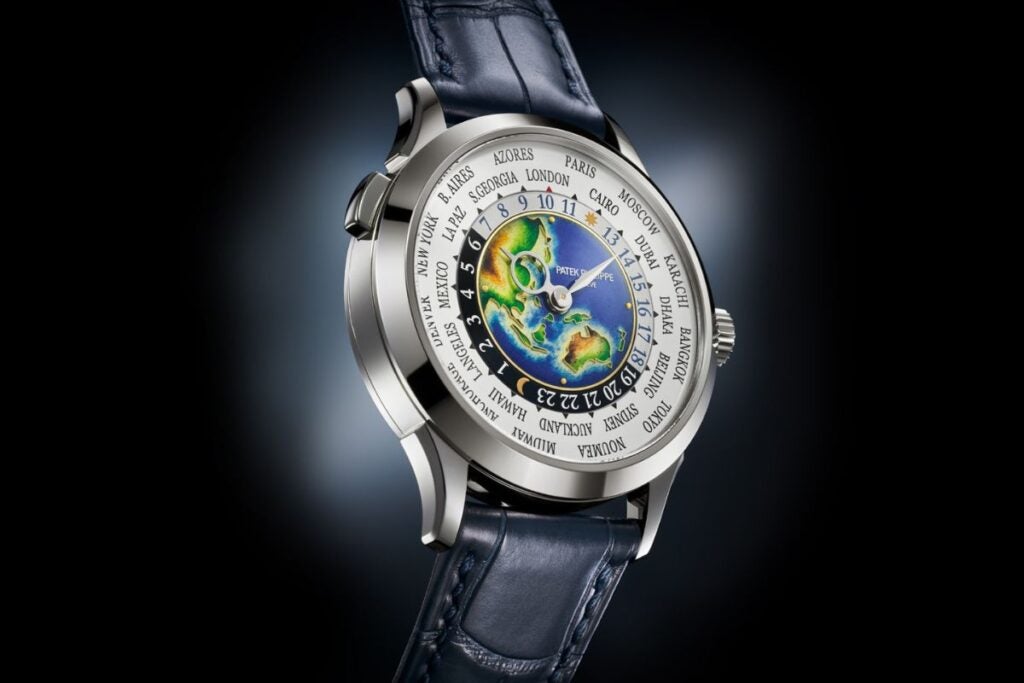

Patek Philippe’s worldtimers

And not for nothing is Patek Philippe particularly associated with the genre, having been the most prominent original adopter of the ingenious system that Cottier came up with in 1931, just as international travel was beginning to flourish. His elegant solution to global timekeeping first appeared in pocket watches, with Vacheron Constantin and Rolex also among his early clients, before he successfully miniaturised the concept for the wrist.

[See also: Patek Philippe squares up to younger buyers with new Cubitus collection]

Patek Philippe introduced its first worldtime wristwatches in 1937, marketing them as ‘for a man whose interests go beyond the horizon’. Until his death in 1966, Cottier personally oversaw the production of these rare birds, which really found their feet in the postwar era as the world moved into the jet age.

Patek’s current versions include the Ref 5330G, which adds an outer date indication that adjusts itself should you cross the international date line; and the rare-as-hens’- teeth Ref 5231G, which has a hand-applied cloisonné enamel dial depicting a map of Asia.

The tradition of enamelled maps and imagery on the centre dial goes back to the 1930s pocket watches; those, and the subsequent wristwatch models that continued the style into the mid-20th century, are among the most prized vintage pieces to be found.

For some reason, Patek seems to have stopped making Ref 5231s with global or northern hemisphere maps (though if you’re VIP enough to be on the list for one in the first place, who knows what accommodations it’ll come to). On the pre-owned market, you’ll need to set aside well over £100,000 for the earlier reference 5131, versions of which carry a world map, and around £85,000 for now-discontinued world map versions of the 5231.

Andersen Genève, the ‘watchmaker of the impossible’

Or else, you could turn to the very wonderful thing that is Andersen Genève. In the Seventies, had you brought your Cottier-made worldtimer to Patek Philippe for servicing, it might well have been entrusted to the hands of Svend Andersen, a young Danish watchmaker whose supreme talents had earned him the nickname ‘watchmaker of the impossible’.

Andersen, now a sagacious 82-year-old, spent a decade in Patek’s Grand Complications workshop, and though the company had stopped making worldtimers in 1966 following Cottier’s death, Andersen was personally bewitched by the concept. Though Patek wouldn’t restart worldtime watchmaking until 2000, he would help create the market for that return.

[See also: Richard Mille revs up with its latest limited-edition McLaren collaboration]

In the Eighties he struck out on his own, producing handmade timepieces to order for collectors, and becoming one of the pioneers of the independent watchmaking movement. In 1990 he finally unveiled his own interpretation of the Cottier worldtimer, having developed a slim, proprietary take on the internal mechanism required.

Known as the Communication, it was lapped up by collectors eager to reconnect with a watch genre that instantly invokes the era when international travel was a genuinely glamorous endeavour.

Today Andersen Genève, the firm he founded, still makes only around 40 to 45 watches a year, from a tiny workshop that is a cluttered wonderland of antique tools, lathes and worn workbenches, overlooking the Rhône in central Geneva. This is horology done the old way: individually, to order, and by hand, with a local network of unimaginably skilled craftspeople – enamel artisans, engravers, gem-setters, polishers – engaged to bring decorative beauty to what’s produced.

[See also: Strike gold with the new raft of bracelet watches]

Over the years, a host of inspired and unconventional designs have borne the Andersen name – automata, jumping hours, complex calendar watches. But it is worldtimers that have remained the flagship Andersen Genève product, with new interpretations appearing every few years, each produced in tiny, highly customised runs.

My absolute favourite is the one made for Asprey, the English maison de luxe, double signed by both brands and with the central dial in ‘bluegold’ (gold that is delicately heat-treated to turn it blue, an Andersen Genève speciality) and engraved with an old Asprey motif. It also has the most beautiful watch case I know: a smooth pebble of polished red gold with striking triangular lugs which, I’m told, have to be made separately and then delicately welded on by hand.

[See also: It’s time to give carbon fibre watches a second chance]

That’s a skill in itself and something almost nobody bothers to do any more; one reason why lugs, the parts that attach the strap to the case and once a distinctively expressive element of watch design, have nowadays become mostly bland and generic.

Unusually, Andersen Genève has its own workshop for bespoke case fabrication in the watchmaking town of La Chaux-de-Fonds, and lavishes as much attention on that element as it does on the dial and innards. The latest fruit is a brand new worldtimer to mark 45 years since the firm’s founding. Appropriately, it goes back to the original Communication model from 1990 for inspiration – particularly in its magnificent, teardrop-style lugs – and takes the name Communication 45.

At the heart of the dial is a cloisonné enamel artwork that will be bespoke for each watch made – of which 45 will appear over the next few years. In this case, the worldtimer is not simply an internationalist statement, but an act of patronage for watchmaking in its most beautiful and skilful form.

This article first appeared in Spear’s Magazine Issue 96. Click here to subscribe