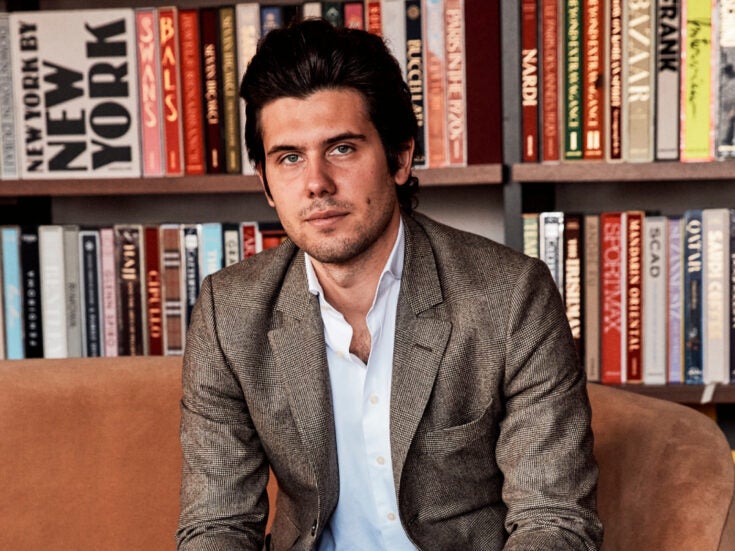

Charlie Pragnell, the managing director and a key figure at Pragnell, a distinguished sixth‑generation British family‑run jeweller with over 170 years of heritage. Since its inception in 1954 in Stratford‑upon‑Avon, Pragnell has evolved into one of the UK’s last full‑service jewellers, renowned for fine jewellery, bespoke creations, antique pieces and prestige watch partnerships, including Patek Philippe and Rolex.

How much is an ounce of gold?

£2,496.

Do you prefer gold or silver?

Gold is very much in style, and that often coincides with high gold prices. Over the last couple of hundred years, you tend to see a 10-to-20-year cycle when white gold is in fashion, then you go through another 10 or 20 years when it’s yellow gold. We’re entering a period of yellow gold. But it all depends upon the piece of jewellery.

[See also: Palau, the remote Pacific idyll that harbours big ambitions]

What was your first pay cheque?

I earned it wrapping presents at Christmas when I was eight in the shop in Stratford-upon-Avon. Jewellery was always around me. My grandfather was the custodian of silver trophies for the Grand National and Goodwood. My father would bring jewels home too. My first real job was a business I started at university in nightclub promotion and student property.

Are you a saver or a spender?

I like to spend money on goods where I’m effectively saving; things that retain value. I like investment pieces, such as art, antiques, watches, jewellery. Property too. I’m more comfortable spending money on things that last. And good family holidays – that’s probably my indulgence.

[See also: London’s luxury cigar scene is under threat]

Pragnell is a storied British business. What’s its history?

Both sides of my family have jewellery in the blood. My mother’s side of the family started as jewellery manufacturers in 1850, going back six generations. On my father’s side, his father, my grandfather, was in the jewellery industry, and on occasion, would look after Queen Mary [wife of George VI and mother of Queen Elizabeth II]. When she died in 1953, my paternal grandfather and grandmother set up a business in his name in Stratford-upon-Avon. My grandmother was a strong lady, and thought it best that my grandfather had a shop in his name.

She chose Stratford-upon-Avon because she recognised that it would be a destination, as the birthplace of Shakespeare. In the 1970s, my mother and father met, and the two businesses were eventually joined. So, from my perspective, we’ve been doing it a long, a long time.

[See also: Fabrics collection celebrates King’s country oasis at Highgrove]

What did you learn about the craft when you worked in California and New York?

My teacher in New York – he was really my master, and I was his apprentice – said to me on my first day, ‘The wonderful thing about the jewellery business is that you learn as much every day as you did on your first day.’ And he was in his late 80s. Ultimately, you’re dealing with nature. The gemstones are natural, and the creativity of the craftsman is a natural phenomenon as well. So you’re dealing with infinite possibilities.

Do you have a favourite gemstone?

I love Kashmir sapphires. But coloured diamonds are fascinating, too; there’s so much variety.

[See also: King’s tailor Anda Rowland on the women shaping Savile Row]

What do your clients love most about the jewellery they buy?

Sometimes it’s for emotive purposes. Sometimes it’s for a show of wealth. Sometimes it reminds somebody of a place, sometimes it reminds somebody of a person. Sometimes someone buys it because they want it to go to their children. Sometimes it reminds them of their grandmother. The point is that it’s individual and unique to each person. That’s the beauty of jewellery. It can be art, or it can be a commodity. It depends.

Tell us about your involvement with The King’s Foundation

Our partnership with The King’s Foundation began a few years ago and has evolved since then. It’s an extremely important charity. The King has been a true visionary; just as he demonstrated remarkable foresight on environmental issues, I believe he also deeply understands the future value of traditional craftsmanship and human skills.

This article first appeared in Spear’s Magazine Issue 96. Click here to subscribe