Christmas party season is upon us, and that means one thing. It’s time to get sociable. The thought of engaging in small talk with colleagues and people you’ve never met before may send a shiver down your spine, but as the Romans well knew, the personal and professional advantages to be gained almost always outweigh the initial awkwardness.

[See also: Could the British Library cyber-attack bridge a social divide?]

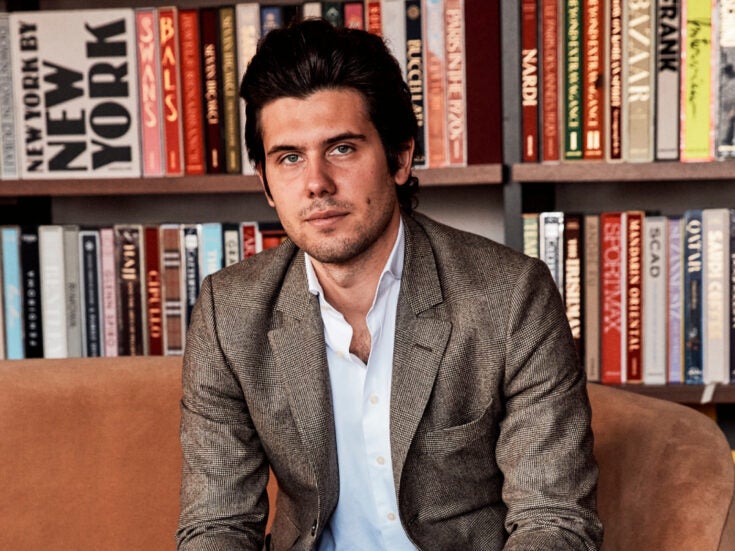

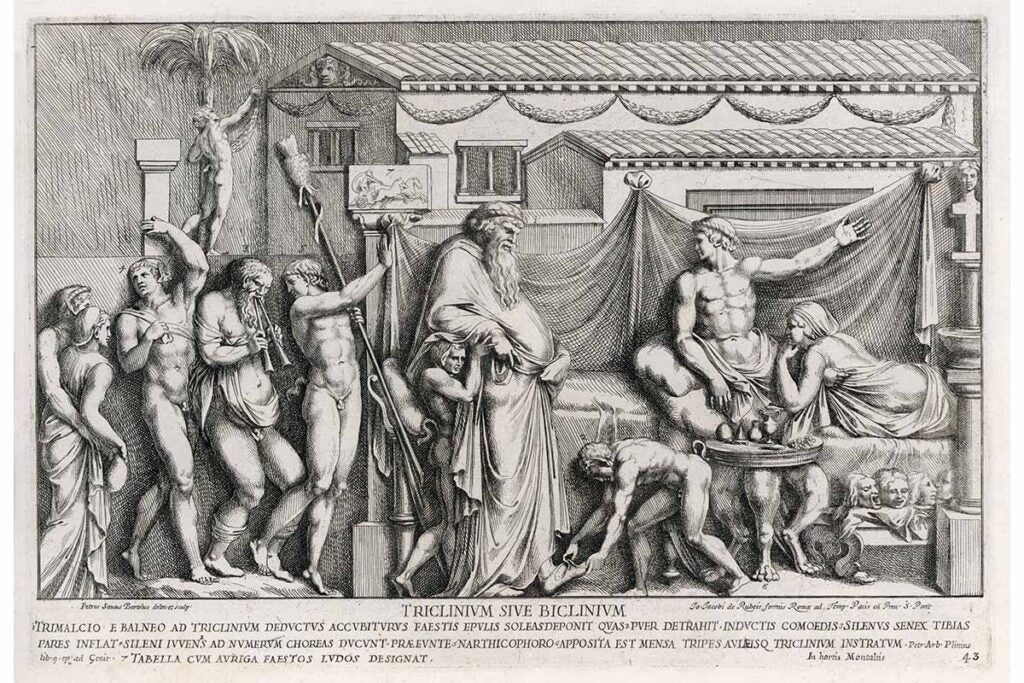

Ancient literature brims with advice for the budding party-goer. Tips range from the bizarre – it was customary in Rome to take your own napkin wherever food was served – to the genuinely helpful. If you are the host, says one Roman author, the first thing to do is en- sure the people you invite are neither too quiet nor too vocal. Trimalchio became a byword for gaucheness in the first century following the publication of an influential satire. The former slave, who found his fortune, talked over his guests and spouted pretentious nonsense across the extravagant dinner table. His story later inspired The Great Gatsby.

Small talk with style

Former slave Trimalchio’s extravagant parties were the inspiration for The Great Gatsby / Image: Alamy

It is interesting to note that Romans involved in public professions, such as law and politics, needed to be reminded to keep conversation light. Many of them had grown up listening to speeches in the law courts before furthering their oratorical education in Greece and the east. Cicero, for example, spent two years in Athens, Rhodes and what is now Turkey receiving instruction in philosophy and rhetoric. Young men typically returned to Italy well prepared for speaking in the forum or the senate house – the Roman equivalent of Parliament – but less adept at conversing with one another in informal contexts.

There were exceptions, the affable Cicero being one, but such characters were inclined to carry on exhibiting their oratorical prowess long after business had closed for the day. As the writer Marcus Terentius Varro subtly implied, this simply would not do, because in Latin otium, leisure, was by its very definition the absence of business, negotium. So Varro advised his readers that ‘eloquence is appropriate for the forum and among the benches of the courts’, but after hours, conversation ought to be ‘pleasant and inviting’.

Anticipating that some might need more guidance here, Varro recommended steering clear of fraught, anxiety-inducing topics, such as certain items of news, in favour of the everyday ephemera of life to which anyone could relate: the sort of thing, he clarified, that one doesn’t usually have the time to discuss in the forum and at work.

The biographer Plutarch later backs Varro up by explaining, without a hint of irony, that it is wise to stick to familiar, uncomplicated subjects when in mixed company so as not to alienate the less intellectual members of the group. Avoid tricksy, sophistic talk, he suggests, and think rather of subjects that even a heavy drinker could throw himself into with gusto. This could be something gossipy or a piece of entertaining news. It could be a story of someone’s courage or a life-affirming act of charity. Or it could be an interesting ditty from history. The most important thing is that the story is delivered unobtrusively. Don’t stand there expecting applause or an admiring pat on the back from your interlocutors.

Everything in moderation

Humour was a desirable but potentially risky feature of sociable conversation. The Romans recognised that some people are much better at telling jokes than others. This gave rise to discussions as to whether humour is something we are born with or something we can learn.

Cicero, who enjoyed a deserved reputation as one of the premier wits in Rome, had two characters debate this very question in one of his rhetorical dialogues. In the De Oratore, Gaius suggests to Antonius that the concept of trying to write a guide to joke-making is ludicrous and in fact far funnier than anything one could glean from the book itself. Humour, Gaius argues, is the one aspect of public speaking which cannot be taught. You either have it, as Cicero also realised, or you don’t. This may sound harsh, but Plutarch’s advice was wise: if you can’t make a joke skilfully, discreetly and at the right time, it’s best to avoid making a joke at all.

And as the evening nears its end, think of the ancients, and avoid being the last to leave. As the adage goes, everything in moderation.