‘Before his 30th birthday he had bought himself a castle in the South of France, an island and a Rolls-Royce (he did not drive it but thought it was a very attractive vehicle).’ Nick Foulkes on possibly the last great French (really French) painter.

As far as I am concerned a book is never really finished – there is always more research to be done, another chapter to be written – but my poor publisher, Trevor Dolby at Random House, was getting increasingly frustrated and it was partially in an effort to bring his blood pressure down to acceptable levels that I handed it in. Rather like a child leaving home, it was out of my life, no longer mine.

It began about fifteen years ago. I had just finished lunch at Le Caprice, then I strolled through St James’s with a cigar. Suddenly my attention was commanded by a painting in a gallery window. It was a still life, not very big, a watercolour, but what it lacked in size it compensated for in drama and suspense. It showed a handgun, some books, a Ricard-branded ashtray on the edge of which rested a smoking cigarette, a coffee pot, and an antique desk lamp with a shade of pleated green fabric tilted to create a cone of light that illuminated the items, causing them to emerge from the black background.

It was as if I had stumbled into a crime scene or a set piece from one of those thrillers that for some reason are called hardboiled. Who was smoking the cigarette? Was it the owner of the gun? How did they relate to the pile of books? It had all the more impact because of the artist’s signature. Right in the middle of the composition, in an angular script that was destined to become very familiar to me, were the two words ‘Bernard Buffet’.

I have to thank that picture for making me aware of his work and his extraordinary life. Over the course of the ensuing years, I would see his works in auction catalogues. I would spot old pictures of him in the jury of the Cannes Film Festival. I would come across old copies of Paris Match in which he would be photographed in one or other of the many castles and grand houses he would own during his life.

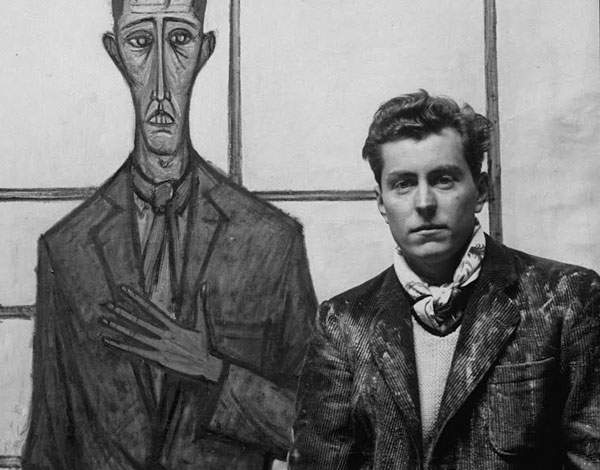

At one time Bernard Buffet had been a big deal, famous and, if the pictures of him looking like a movie star in his dinner jacket were anything to go by, unafraid to embrace the material pleasures that this success had afforded him. Before his 30th birthday he had bought himself a castle in the South of France, an island, a small yacht and a Rolls-Royce (he did not drive but thought it was a very attractive vehicle). He wore Charvet shirts and was a connoisseur of everything from Galle glass to cowboy boots. He moved from one grand house to another for the rest of his life. This heroic accumulation of material possessions alone deserves to be saluted.

His problem was that being driven around in a Rolls-Royce and living in a castle rather jarred with the fact he had become famous as the painter of Parisian postwar misery – coffee grinders, emaciated chickens, battered cooking pots – work that had seen him hailed as the successor to Picasso in his twenties. For most of the Fifties he was the lover of Pierre Bergé. But by the time he was 30 the critics had turned on him as too commercial and, when Bergé left him for Yves Saint Laurent, he married Françoise Sagan’s lover Annabel, a singer and novelist, and together they became pillars of Paris Match Society, stalwarts of Castel’s and Maxim’s.

Thereafter at various times he was a jet-set socialite, a Howard Hughes-style recluse, alcoholic, drug addict and, throughout, an incredibly prolific painter; no one knows how many works he produced but 8,000 oil paintings (not counting watercolours, drawings, engravings and so forth) is generally accepted as the minimum. During the Seventies and Eighties, he became huge in Japan, where a museum was opened in his honour. But in Europe, his reputation languished for years and was at its nadir when I first became aware of him. Now it is undergoing a spectacular revival, and there will be a major retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art in Paris next year.

Buffet might well be the last great French painter, I mean really French painter: he loved his homeland, he painted it endlessly, he did not see the need to speak any other language than his mother tongue. Paris had been the centre of culture, fashion, food and civilised living forever and although the Second World War had tarnished the reputation of the city, Buffet was one of a constellation of young stars who showed that France still had ‘it’: Paris’s post-war bratpack included, among others, Brigitte Bardot, Sagan, Saint Laurent and Roger Vadim.

His was a compelling life and I have to say that in finishing the book my biggest sadness was that I had to leave it and return to my own rather dreary existence.