How the US’s new breed of tech entrepreneurs conquered the world, and how the underclass didn’t. Reviews by Peter York and Christopher Silvester

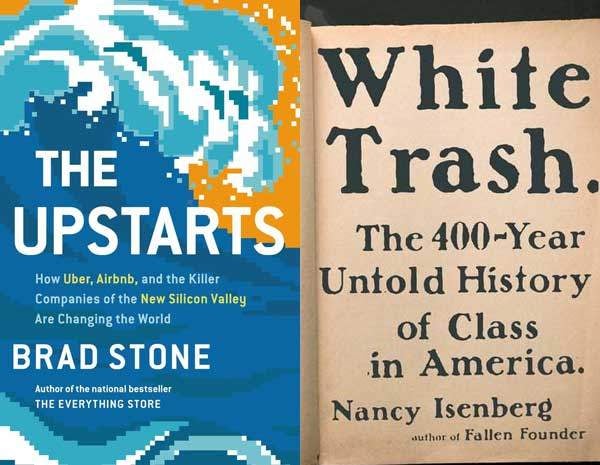

The Upstarts: How Uber, Airbnb and the Killer Companies of the New Silicon Valley are Changing the World by Brad Stone

In my epic 2015 stand-up debut at the Edinburgh Fringe, ‘How to Be a Nicer Type of Person’, I played two pieces of video that always got more laughs than I did. One of them was a US Airbnb TV commercial. It was so gorgeously pious about the slightly creepy experience of sleeping in a stranger’s bed and experiencing their lives as to project the company as a 21st-century United Nations, bringing people together and teaching the world to sing. The voiceover had my audience on the floor. This kind of corporate sentiment, especially coming from a Silicon Valley kind-of newcomer, hit a hilariously wrong note.

Airbnb, and its contemporary Uber, the car transportation organiser, are the stars of Brad Stone’s The Upstarts (a clever reversal of start-ups). I say ‘stars’ because these kind of business bios have a hardcore of readers – geeks, wannabe entrepreneurs – for whom people like Airbnb’s Brian Chesky or Uber’s Travis Kalanick are more compelling role models than anyone in Hollywood. There now exists the notion that a new kind of tech entrepreneur can be a player – no longer a pure-breed geek like Mark Zuckerberg in his pyjamas (in The Social Network, Jesse Eisenberg played him as being a bit, you know, on the spectrum-ish), or the Google boys Larry Page and Sergey Brin, but someone whose jumping-off point starts later, with the internet and uptake of smartphones as a given.

This engaging account of Uber and Airbnb and their precursors and competitors, and how they got to a joint valuation of pushing $100 billion in less than a decade, is pitched straight into a new world, one of rough politics, tough campaigning and a combination of ruthlessness and high-minded rhetoric.

As Stone points out, this generation of entrepreneurs faced competition and regulation practically from the word go (unlike Bill Gates or the Google boys, who had some quiet years to develop their products before anyone noticed they were changing the world). This is because they’ve manipulated real things (houses and cars) and outsiders’ livelihoods (householders and drivers) without owning anything except heavily protected IP, some algorithms, and tough lawyers and public affairs people. And fancy offices.

Uber and Airbnb are, as Stone points out, interwoven in location, milieu and attitude. They know each other. Kalanick even had a flat-sharing idea called Pad Pass once. And they both have predecessors and contemporaries with similar ideas – but the success factors that mattered were luck and relentlessness.

Both company’s trajectories have involved sailing close to the wind with regard to transport and zoning laws and then defending themselves with claims of vested interests – insisting that regulations were really just the cab companies and hotel businesses maintaining their privileges. Sometimes, Stone says, they’d then act nice about it (Airbnb was apparently better at that than Uber), or say they didn’t know the small print and were only trying to help people.

Both companies expanded rapidly, under the radar in some cases, hotly contested in others (taxi drivers can be an excitable lot, and in places they did their own kind of motorised rioting). And their lobbyists leant on any lawmakers they could find. The status quo’s PRs produced stories about unregulated taxi drivers as rapists and how the new, short-term landlords were making areas no-go zones for hard-up local renters.

In Airbnb and Uber you can see the great debates of the modern world played out. They both combine the new Darwinian rhetoric of disruption or Schumpeter’s creative destruction, with the idea of ‘empowerment’ for drivers and micro-landlords. And they certainly have their fans. Driving for Uber suits some people who do it to augment their income or change their hours (but how they laughed when Uber once claimed its New York drivers were making $90,000 a year). And Airbnb suits those who don’t want

to downsize, or the new breed of buy-to-let landlords who rent out properties solely using this service.

It’s difficult to sort out the competing stories and divine whether the ‘sharing economy’ is really the gig economy, meaning a zero-hours-contract world ruled by the people with the algorithms. But Stone makes a good fist of it, provoking you to work it out for yourself. He’s shaping up nicely, is Brad – less poncy than Malcolm Bradwell and less epic than Michael Lewis, but a sound guide to the real new New World.

White Trash: The 400-Year Untold History of Class in America, by Nancy Isenberg

The term ‘white trash’ first appeared in print in 1821 and gained common usage in the 1850s, but the actual phenomenon reached back to the origins of the American republic and even beyond that to the earliest colonial settlement of North America and British notions of poverty.

‘Our class system,’ writes Nancy Isenberg, ‘has hinged on the evolving political rationales used to dismiss or demonise (or occasionally reclaim) those white rural outcasts seemingly incapable of becoming part of the mainstream society.’

The US social scientist Charles Murray once subscribed to the conceit that has ‘prevailed from the beginning of the nation: America didn’t have classes, or, to the extent that it did, Americans should act as if we didn’t’. The purpose of Isenberg, a history professor at Louisiana State University, is to blow apart this version once and for all.

Neither early Massachusetts, where citizens were allocated church pews on the basis of property holding, nor early Virginia, where planters got rich from tobacco, can be described as classless. As envisaged by 16th-century promoters of colonisation, America needed both ‘lusty men’ and ‘waste people’. By the latter they meant paupers and criminals, especially ‘fry’ (children), who could be transported as indentured servants. Before the first cargo of African slaves arrived in 1638, these servants were treated as chattels, capable of being bought and sold.

Within the colonies, those at the bottom of the pile were described as ‘offscourings’ (human faecal waste). When the Carolina colony was founded in the reign of Charles II,

the English Enlightenment thinker (and investor in African slavery) John Locke wrote its Fundamental Constitutions and envisaged a pseudo-feudal system of land ownership, as well as an hereditary peasant class. Things did not quite go according to plan and the northern part of Carolina, with its swampy terrain, became a dumping ground for Virginia’s landless. Isenberg calls it ‘the first white trash colony’.

Northerners saw slavery as maintaining white trash in their pauperised state, while Southern planters saw it as a means of obscuring class divisions among whites. Expansionists fretted about the possibility of waste people spreading across the continent like a contagion, so while Free Soil campaigners wished to emancipate African slaves and ship them back home, they still believed in the threat of degenerate breeds. Jefferson Davis, the Confederate president during the Civil War, scorned the Federal Army as being recruited from ‘mudsills’ or the ‘offscourings of the earth’.

‘In a culture under siege,’ says Isenberg, ‘white trash meant impure, and not quite white.’ Eugenicists advocated the quarantining and sterilisation of inferior and diseased breeds. Even Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, one of the most revered of US Supreme Court justices, ruled in 1927 in the case of Buck v Bell that sterilisation was a civic duty, necessary to prevent the nation from being ‘swamped by incompetence’.

With Elvis Presley, The Beverly Hillbillies, and The Dukes of Hazzard, US popular culture co-opted a palatable version of white-trash culture as a subject for gentle satire, while various politicians have sought to define themselves in relation to these marginalised people. Bill Clinton, the ‘Arkansas Elvis’, was the ‘Yale liberal [who] wore blue suede shoes’. Donald Trump declared his love for the poorly educated, whom Hillary Clinton called ‘deplorables’ for being Trump’s dupes.

There is little doubt that Isenberg’s sympathies are more with Bernie Sanders than with Trump or Hillary, but her book offers no prescription for dealing with America’s underclass beyond a more honest recognition of this ‘central, if disturbing, thread in our national narrative’. It is strewn with nuggets – for example, I never knew tack was a degenerate breed of horse that lived in the Carolina marshlands, hence ‘tacky’ – but the most striking thing is to discover the scorn that so many Americans have directed towards their underclass throughout the past five centuries.