When it comes to encouraging wealthy people to be more philanthropic, the carrot is better than the stick.

That’s the view of Sainsbury’s heir Fran Perrin, who was among the speakers at the Giving and Impact Summit at the London Stock Exchange yesterday.

‘I don’t think it works, hitting people over the head with a stick and saying, you know, “Bad, rich people – bad!”’ Perrin said. ‘That doesn’t work very well.’

Perrin’s remarks followed the publication of research commissioned by the organisers of the summit, which found that the top 1 per cent of UK earners donated just 0.2 per cent of their gross income to charitable causes. On average, the figures equate to someone earning £312,000 per year donating £52 per month.

Wealthy people are more likely to give greater sums if they understand ‘how satisfying, rewarding it can be’, Perrin said. She added that the UK would benefit from creating a culture of giving: ‘If you’re very privileged – whether you’ve been born into money [… or] you’ve created [your own wealth], it should be the norm that giving is part of what you do.’

Perrin (who is the daughter of Lord Sainsbury and the great-great granddaughter of Sainsbury’s founder John James Sainsbury) is the founder and director of the Indigo Trust, which supports early stage organisations to address ‘systemic injustices’.

Perrin added: ‘I also don’t think we should have a false dichotomy between tax or giving. I think we should be expecting you to both pay your taxes and do philanthropy.’

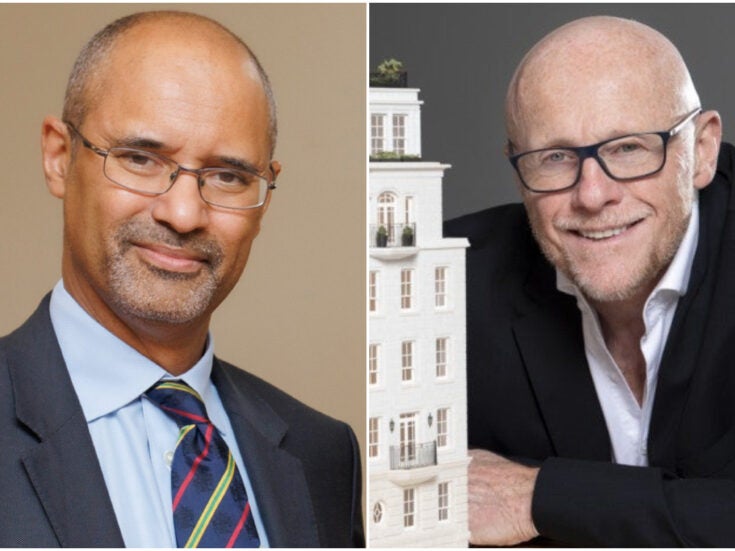

Billionaire entrepreneur John Caudwell, who founded children’s charity Caudwell Children in 2000; Tom Ilube, chair of the King’s Trust; and Stephanie Peacock MP, Minister for Sport, Media, Civil Society and Youth also spoke at the summit, which was presented by communications, reputation and social impact consultancy, Integra, and supported by partners including Spear’s, private equity house KKR, the British Red Cross and Renaissance Philanthropy. Later in the day Deborah Meaden and Rob Rinder were among those to attend the closing ceremony of the London Stock Exchange as part of the Giving and Impact Summit delegation.

Caudwell called upon his fellow billionaires to do more to address the divide between rich and poor, which he described as ‘absolutely appalling and growing by the day’.

Caudwell said he was ‘going to pick on Jeff Bezos’, but only because the Amazon founder’s recent wedding to Lauren Sanchez meant that he was ‘topical’.

‘I don’t know what [Bezos is] worth at the moment. I mean, two or three-hundred billion? [The latest figure according to Forbes is $236 billion.]

‘I’ve often said that if he donated 99 per cent [of his net worth] he’d still be left with three times the amount of money that I’ve got …. And he’d be the hero of the world.’

Caudwell, who is a signatory of the Giving Pledge, has committed to giving away 50 per cent of his wealth ‘during or after my lifetime’.

‘[Bezos] doesn’t have to do it in his lifetime,’ said Caudwell. ‘He can just say 300 billion is going to charity during or after my lifetime. And everybody would think: “Wow!” […] They wouldn’t think, “Well, Jeff Bezos has spent 50 million on a wedding in Venice!” … Why wouldn’t you do that? Why wouldn’t you get that kudos for wanting to change the world?’

Caudwell added that around 250 of the world’s billionaires had collectively pledged $600 billion through the initiative, which was launched by Bill Gates, Melinda French Gates, and Warren Buffett in 2010. ‘But it’s only a small percentage of the world’s billionaires. […] If we could inspire all the billionaires to join the Giving Pledge, that sum of money to change society would be $11 trillion.’

Some of the world’s billionaires are reluctant to engage in large-scale philanthropy for fear of sliding down the rankings of the world’s richest people, said John Studzinski, managing director and vice chairman of investment management firm PIMCO. ‘I’ve told the two or three wealthiest people in India; I said: “You have 30, 40, 50 billion – you should give away 90 per cent of that.” Their first reaction is: “If I did that, I would no longer be very well ranked in the wealth table.” And we all know who they are.’

Studzinski added that attitudes to, and definitions of, philanthropy varied significantly in different parts of the world. Whereas Indian billionaires might think, ‘We employ people, and because we create such employment, that is our philanthropy,’ Americans were more likely to engage in ‘social philanthropy’, which he described as ‘a gimmick to raise short-term money’ and ‘more of a social networking exercise’.

‘I think you want everyone, regardless of how poor or rich they are, [to be philanthropic],’ Studzinski said. ‘Everyone has a responsibility just to channel a certain amount of their time and their talent for the common good … It should be a way of life. It should not just be something you do once you’ve accomplished something else.’