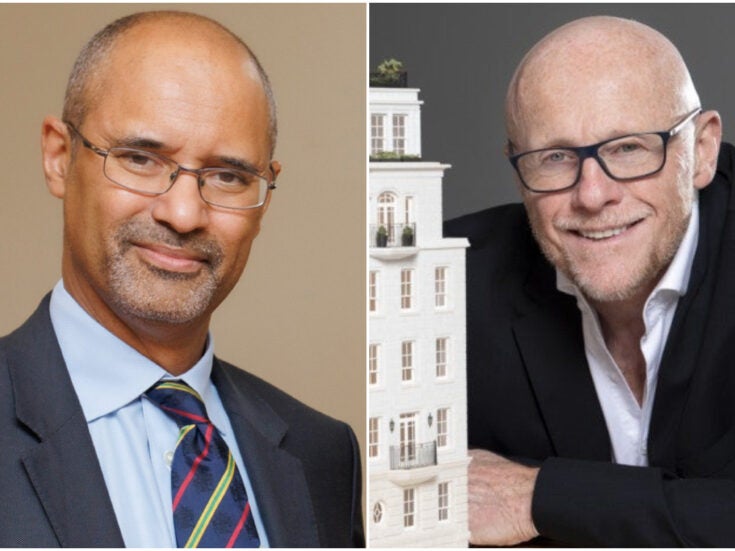

I have a new hero: René Olivieri, chair of the National Trust. He begins the interview by asking me about a book I once wrote. Fair enough, as we’re in the former stables of Osterley Park, on the Heathrow side of London, where the main house is being readied to contain the late Sir Brinsley Ford’s collection of Baroque paintings. But the idea that this busy man would remember my modest volume – hardly a bestseller – makes its way (as possibly calculated) straight to my heart.

Olivieri has horses himself; they live at his house in Worcestershire, where his German wife Anne has created an outstanding garden, which is opened to the public several days a week. (‘If you want to keep me, I need a Georgian house and a big garden,’ she told him 27 years ago. ‘Of course, I did want to keep her, so I said yes.’) Profits go to the Royal Shakespeare Company, theatre being a big love. All of which are fine attributes for the head of one of this country’s greatest treasures. But there’s more, some of it surprising.

For example, although a naturalised British citizen, he began life in distant Oregon. There are clues to American genetic inheritance in the lanky frame, the centre parting, the air of being an Ivy League professor, the hint of an accent that I would have put down as Canadian – but who would have thought that he grew up on a small farm, so remote that his school was dozens of miles away?

[See also: Prominent philanthropists call for UK to give more]

‘It seemed very isolating at the time,’ he says, although on a return visit, made as an adult, he found Mounthood and its forests so iconically beautiful that they might have decorated a beer can – a quality he had not noticed when growing up.

Admittedly, it was not a Grapes of Wrath sort of farm. His parents had bought it in pursuit of the good life, thought to exist in the simplicity of the sticks, although Nature was not quite so bountiful as they’d hoped. Escape came when, at 17, he spent a year in Belgium on an exchange programme. This took him to Flanders and a small town outside Bruges, where he found his classmates studying Greek and Latin and – equally incomprehensible – speaking Flemish.

‘It’s not that difficult a language,’ he maintains (he now speaks German at home). Once fluent, he plunged into history and toured the cathedrals of France. America was a wonderful place, he concluded, but he needed the cultural richness and historical depth offered by Europe – and ultimately the National Trust. He has just completed his first three-year stint in the chair and is now on to his second.

These have been squally times for the trust. Once, it seemed as unassailable as the NHS or, in those distant days, the BBC: above party politics and beyond reproach. But controversy came knocking earlier this century with the hunting debate – one of the manly sports of the countryside often pursued by (former) owners of its country houses. This was followed by the great bean bag debacle of 2015, when furniture was removed from Ickworth House in Suffolk (for restoration) and replaced by squidgy pouffes you could lie on to look at the ceiling.

A focus on the queer side of the trust – not unreasonable, given that several country houses were left to it by gay men who were the last of their family lines – caused another storm, when past donors were outed and volunteers were compelled to wear Pride lanyards and scarves against their beliefs. Resentment simmered, until the lid blew off the pressure cooker with the appearance of a poorly researched audit of links to slavery. It fingered Sir Winston Churchill, who built Chartwell, despite his having ‘personally fought in a war to end slavery’ in 1898, according to the historian Lord Roberts.

An old guard of country-house visitors, supported by former employees of the trust, was – in some cases literally – shaking with rage. It formed the cleverly named Restore Trust, a pressure group intended to stem the tide of wokery via measures such as championing a slate of traditionalists and aesthetes for election to the ruling council.

Part of the trouble for the angry brigade is that the focus has shifted. As James Stourton describes in his 2022 book, Heritage: A History of How We Conserve Our Past, this is generational. There was huge public interest in the future of country houses after the ‘Destruction of the Country House’ exhibition at the V&A in 1974, and debates raged about paint colours and principles of display (Osterley itself, then run by the furniture and woodwork department of the V&A, was a battleground).

[See also: James Reed: Why entrepreneurs should make philanthropy part of their company’s DNA]

But reductions in income tax, combined with the whopping endowments required by the National Trust, meant that many owners preferred to put their homes into charitable trusts rather than surrender control. So the supply of new properties to the National Trust dried up – and besides, it already had a bulging portfolio. Now all the excitement is in the environment, which is threatened on all sides, just as country houses had been in a previous generation.

To Stourton, the shift was inevitable. The country houses remain; they’re well maintained; the pendulum may swing back. To restore trust, the change of priorities represents the betrayal of a sacred mission.

Olivieri, in his early seventies, takes all this in his loping stride. A survey of the 5.7 million members showed that most of them do trust the trust. How many members? Yes, 5.7 million – that’s more than the population of Norway. Members mean money, which is good for a charity that, like others, struggled to get back on to its feet after Covid, when properties were closed and income plummeted.

They also represent something of a challenge. A generation ago, the trust gave the impression of being staffed by brogue-wearing scions of the aristocracy – or people who would have liked to be scions – with a membership cut from the same tweedy cloth. It was a club of people who shared the same tropes and values, barely considering the needs of those outside their magic circle. Estate cars displaying a National Trust badge were generally a liability on the road. Inevitably, today’s mega-membership is not so homogeneous or cohesive.

There are fewer cowpat-coloured jackets, more pushchairs and Lycra. Not everyone wants the same things. And just look at the sprawling and varied nature of the portfolio: more than 300 houses, nearly 50 industrial monuments, 11 lighthouses, 39 pubs, 41 castles and chapels, 56 villages, 37 medieval barns, 140 hillforts, 175 ornamental lakes, more than a million items in the collections – as Winnie the Pooh’s friend Rabbit said of his many pockets, ‘I haven’t time.’ This needs big-picture thinking. Fortunately, this plays to Olivieri’s strengths – and being a non-executive chair, who can leave the day-to-day running of the trust to director-general Hilary McGrady, he has the bandwidth to do it.

In his business career, Olivieri ran Blackwell Publishing, the academic press that was sold to the American John Wiley & Sons for £572 million in 2006. There he started a journal of bioethics to support his concern for farmed animals: ‘I had suddenly realised that not all farms were like the one I grew up on.’

[See also: The best philanthropy advisers in 2024]

Afterwards he became a trustee of a spend-out charity whose object was to give away its endowment of £65 million within 8-10 years. The board decided to support organisations it thought would continue in existence for many decades. At the National Trust he is looking further. What will the world be like a century from now? What decisions will the people of the future wish we had taken in 2024? As an economist his foci are natural and social capital, both of which are being degraded – particularly in cities, where people increasingly live. So he wants the National Trust to partner with other funders to restore the parks and historic sites that local authorities cannot afford to maintain, joining up natural environments and places of interest.

‘We’re already doing that in Bath,’ he says. ‘We [plan to] expand it to 100 different cities, so that people will able to walk outside the door and within 10 minutes find access to quality green space where they can play, they can sit, they can rest, they can enjoy nature…Unless we can inspire everybody to care about this stuff, we worry that in the future nature and heritage history will become neglected or become a minority pursuit. We want people to realise those things are absolutely central to their well-being.’

Climate change has already hit the trust. Flooding, drought, pests and extreme weather bring extra costs. Foundations beneath buildings are drying out. As a landowner, there are things the trust itself can do to help, such as restoring peat bogs – drained with the help of government grants in the 1970s – so that they hold more water and absorb carbon. Rewilding is a popular cause in some quarters, but the ‘re-’ is redundant: nothing has been truly wild in the densely populated British Isles for millennia. Instead, Olivieri believes landscapes should be understood, like the properties, as historic documents.

He has plans for those properties too. Out of the trust’s portfolio, 30 will be chosen for the full beam of historical research. They’ll become ‘world destination sites, on the next level of interest and involvement’.

At the other end of the scale is Munstead Wood, a modest dwelling in comparison to Hardwick Hall (where the long campaign to restore the 13 Elizabethan tapestries has just been completed) or Knole Park (home to a world-class restoration centre in a newly converted barn) but of huge importance as the home that the young Edwin Lutyens built for his mentor, the gardener and craftswoman Gertrude Jekyll. The trust bought it in 2023 out of its reserves, not in the hope of a financial return, since the place is too small to take many visitors. (Full disclosure: I was chair of the Lutyens Trust when it happened.) So far, the approach has been impeccable.

And that’s typical of the National Trust: a loose, baggy monster of an organisation, responsible for everything from rare ants and deer herds to the Lake District and Chelsea porcelain, in which the occasional bean bag or fluffed report causes a media flurry but is outnumbered by examples of quiet excellence. It breathes history through every pore.

To Olivieri, this is key. ‘I think the way we’re going to solve the problems in the natural world is by giving people the ability to imagine themselves 200 years ago. That primes them to imagine there will be a world inhabited by people 200 years after.’ What a man.

Clive Aslet’s Sir Edwin Lutyens: Britain’s Greatest Architect? is published by Triglyph Books

This feature first appeared in Spear’s Magazine Issue 94. Click here to subscribe