It was some years after his wire-walk between the Twin Towers of the World Trade Center that I first interviewed Philippe Petit, but his wire-walk seemed as fresh as yesterday. Petit had been plotting his ‘criminal action’ — his phrase — since reading about the towers-to-come in a French magazine. The towers went up. He came to New York, reconnoitred, sneaked in the wire, did the crucial rigging with an assistant and set out 1,350 feet above the ground just after 6am on 7 August 1974.

He stayed up there for 45 minutes, sauntering, dancing, sitting, lying lengthwise and jumping, his feet leaving the wire. But it had begun to drizzle, so he brought his performance to a close and was at once arrested by the cops who were waiting on both roofs. But there were no charges.

We lunched appropriately in Windows on the World, a terrific eatery on the top of the WTC’s North Tower. Just looking down through thick glass was giddying. Petit was controlled, laid-back, un-showbizzy, a working performer. Indeed, when I brought up what I assumed would be a delicate subject — the death of a famous wirewalker, Karl Wallenda, who had recently fallen in Puerto Rico — Petit merely observed that Wallenda ‘didn’t do his own rigging’.

There’s another distinction. Wallenda had been head of the Flying Wallendas, a circus clan. When Nik Wallenda, his great-grandson, wirewalked across the Grand Canyon in June 2013 it was screened on the Discovery Channel and he was promoted as a ‘daredevil’, a stunt man, like Evel Knievel. Petit, meanwhile, went to one of the best art schools in Paris and from the beginning has defined what he does as art. After the WTC walk, he turned down $1 million to do a beer commercial and has consistently refused all such offers.

It seemed fitting that not long after our lunch he was appointed artist-in-residence at New York’s Cathedral of St John the Divine; likewise that he was asked to join the heavyweight Pace Gallery.

Interesting timing. Extremes of performance art were increasingly coming on to the art-world menu. On 23 April 1974, a young Californian artist, Chris Burden, had himself crucified to the roof of a VW Beetle in an alley in Venice, California. The piece was called Trans-Fixed. The next month, Joseph Beuys flew from Düsseldorf to New York and spent six hours a day for three days with a coyote in the Rene Block Gallery, making I Like America and America Likes Me.

Burden (now with Gagosian) and Beuys (deceased) are museum artists, but perhaps Petit seemed too much of a circus act for Pace, as that relationship was terminated. Flash-forward to 2008, however, and Man on Wire, a documentary about Petit’s WTC walk, won at Sundance. The movie again made him one of the best-known performers in the world. But, more importantly, it made it transparently clear that this man is not a stunt man, but an artist.

Which brings us to the present. In August Petit celebrated the 40th anniversary with a walk over a pond at the Longhouse Reserve, a non-profit sculpture garden on New York’s Long Island. It was a good day for it: sunny but not blistering. Several rows of chairs were set in front of the pond, which was so rich with exotic vegetation that you half expected to find Claude Monet there with an easel, and there were so many lines above it crossing in different directions that it was hard to puzzle out just where we would see Petit walking across the sky. Then a sharp-eyed woman pointed out a ladder leaning against a tree on the side of the pond. ‘He’ll come towards us,’ she guessed.

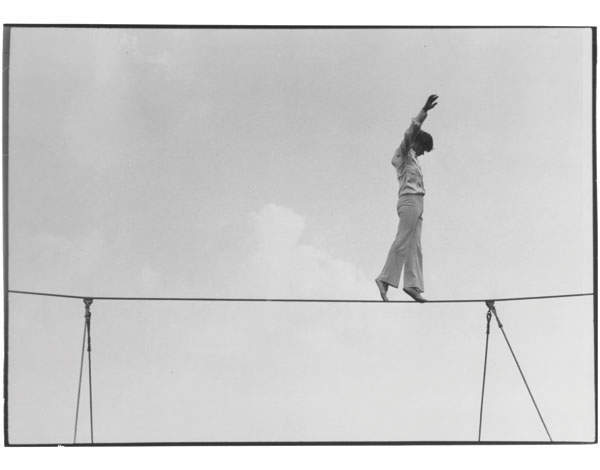

And so it proved. Petit appeared in white and began walking the wire. During his crossings, two performers with whom he has worked before did their stuff: Paul Winter played the saxophone and Melissa Leo, an actress, read texts written by Petit himself.

In advance I had been unsure how I was going to react. This was not the Impossible — the Eiffel Tower, the Sydney Opera House — this was a walk above a pond. But Petit had spoken to this issue earlier. ‘I have the luck of not being born in the circus,’ he told me. ‘So I didn’t follow the tradition of the costume, the pratfall, the danger. I came from the world of opera, theatre, poetry, art, and therefore when I learnt the wire what I wanted to do was not frighten my audience but inspire them. I dedicated myself to walking, you know, the art of walking, which is so simple that it is extremely difficult.’

And to do what for most is not possible? ‘Yes. Yes. People are touched by seeing somebody walking in the sky because they cannot imagine being there. It is like a miracle. And to me too when I see a wire walker, talented or not, I think a miracle is happening now!’

Petit walked the wire back and forth four times, varying the walks with little routines from time to time. At one moment he walked forwards jauntily, as though walking on to a dance floor, at another he was lifting one leg, then another, at yet another he lay down full length on the wire. I would later learn that these were precisely the routines he had used during Le Coup, as he calls the World Trade Center walk, and that this wire was the same length as the World Trade Center wire. It’s a very specific piece.

It was also an art piece — the saxophone, the texts — but it was, when it came down to it, only above a pond. The WTC it wasn’t. But Petit had spoken to this issue too. ‘I can walk thousands of feet above concrete,’ he said. ‘It doesn’t bother me. But water terrifies me. It is not my element.’

Philippe Petit, it emerged, cannot swim.

Petit’s working business model is often compared to that of Christo, and there are resemblances in that the projects of both can take years before they come to fruition, if indeed they do so ever. Also, neither accepts commissions nor sponsorships.

That aside, the differences are deep. Christo finances his hugely expensive projects — the current ones have already cost him way above $20 million — by selling the art that the projects generate, but he considers those artworks residue. The experience, the event, is the real art. Petit, who has written a number of books, keeps journals of his projects and is an accomplished draftsman and modeller. But little of his art has, as yet, been widely seen. He remains Man on Wire. And at 65 these projects show no signs of abating. What are his future plans?

‘It’s strange because I have two kinds of plans,’ Petit said. ‘And they are very different.’

The first are the commissions, which pay the rent in Woodstock, where he lives with his long-term producer, Kathy O’Donnell. The most imminent is for the Boston Institute of Contemporary Arts. ‘It’s a walk over the bay,’ he says.

The second kind of plan? ‘I am searching into my brain for things I want to do — which, of course, are projects of a very different kind,’ Petit says. ‘Then I have struggles to find the money, to get the permission, to get the things in gear. I have a walk on Easter Island which is a project of mine for many, many years. A friend who worked with me on Longhouse is in Easter Island and they are all very excited.

‘Also a very old proposal seems to be alive again. It is my walk from the Sydney Opera House to the Sydney Harbour Bridge. I started the proposal in 1973 and it was very close to happening a few years after that, and then it completely evaporated. Now one of the friends who helped me put a wire at the bridge in ’73 is a movie executive, and he is trying to revive the idea.’

He will also appear in a Broadway show, and there is a feature movie, The Walk, in which he is played by Joseph Gordon-Levitt, in post-production. It will come out next October. There is also to be a major gallery show, which will bring together the drawings, the models and the videos — all the elements in what has been, shall we say, a fairly remarkable art career. And a singularly appropriate art career, I think, for our scary times.