The Amazon billionaire has introduced a bold alternative to legal action, write Jennifer Agate and Erika Federis-Cox

How many individuals, threatened with the exposure of intimate photographs, would be brave enough to address the problem head on through an open tweet?

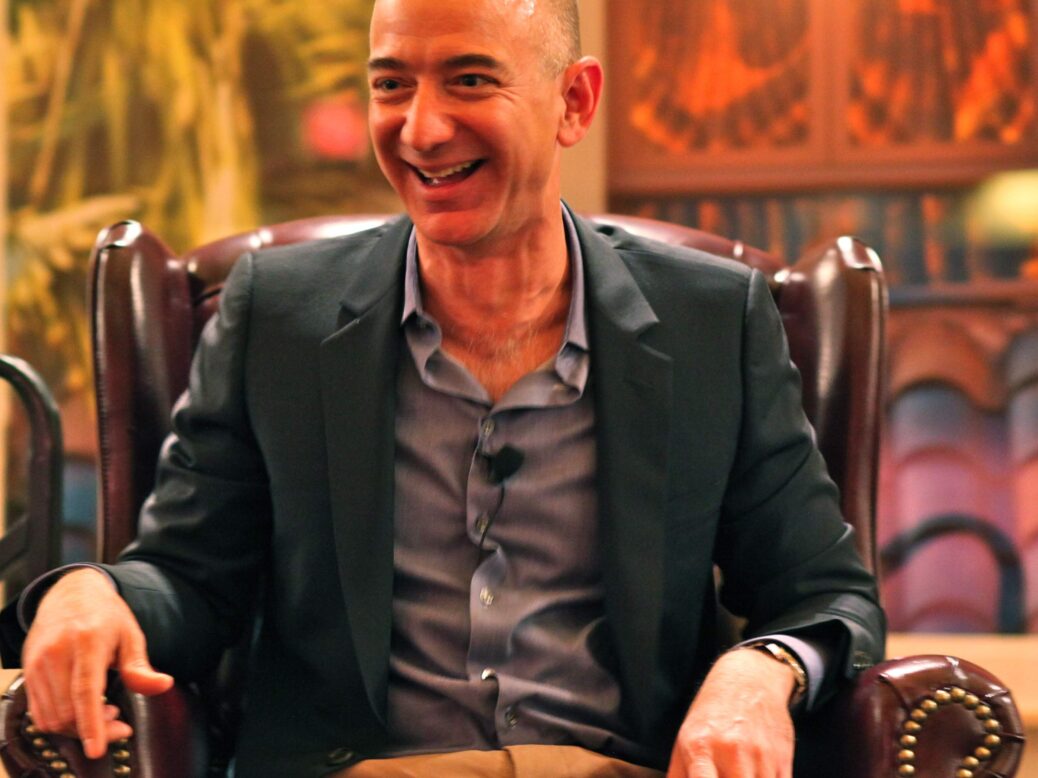

On 7 February, Jeff Bezos accused the National Enquirer’s owner of extortion and blackmail. He didn’t do this in a lawyer’s letter (although we have no doubt many of those followed too), but in a blog post widely shared on social media site Twitter.

The news organisation had reportedly threatened to publish intimate photos said to have been shared between the Amazon founder and ex- news anchor Lauren Sanchez, the publication arguing the photos to be ‘necessary to show Amazon shareholders that [Bezos’] business judgment is terrible’. In an extraordinary move, and despite his lawyers’ involvement behind the scenes, Bezos responded by publishing a lengthy blog post on the matter, wittily entitled ‘No thank you, Mr. Pecker’. Acknowledging the ‘potential cost and embarrassment’ disclosure could cause, the post voluntarily revealed the existence of the incriminating photos, together with an unusual level of detail as to the alleged content of the photos.

Only a few weeks prior, intimate texts between Bezos and Sanchez had been published by the Enquirer for all the internet to see. Perhaps unsurprisingly, this lead to Bezos employing the classic strategy of hiring investigators to discover how the messages had fallen into the hands of the press. The emails disclosed in Bezos’ intriguing blog post suggest that the Enquirer had threatened to publish more incriminating material, unless Bezos called off the investigations. While public relations has an invaluable role to play in mitigating reputational harm, such an open and public response remains a brave move.

Will we see the repetition of this bold strategy anytime soon? In the UK, high profile individuals threatened with the release of intimate photographs more often reach for the law, a privacy injunction being the favoured approach. But as many high profile figures including most recently Philip Green have found, in certain circumstances such action can backfire; campaigns against the ‘gagging of the press’ catching the public imagination. Where the individuals have an international profile, the injunctions can be frustrated by foreign publications. That’s not to say that injunctions don’t still have their place, but they do have to be used with caution.

In the Bezos case, had the circumstances occurred in England, the allegation of blackmail is likely to have been a persuasive factor, at least in obtaining an interim injunction (the allegations would have to be proven to succeed at trial). Blackmail, a serious criminal offence carrying a maximum sentence of 14 years’ imprisonment, has proved the tipping point in many privacy cases involving intimate revelations.

Where photographs are shared with the intent to cause distress, criminal proceedings under ‘revenge porn’ legislation also come into play. Any person found guilty of this offence could be liable to imprisonment for up to two years, and/or ordered to pay a fine. Sadly many victims of revenge porn (if this is what it is) don’t realise they have any recourse when things take a turn for the worst. As Bezos himself says, ‘If in my position I can’t stand up to this kind of extortion, how many people can?’

Photo credit: Wikimedia Commons

Jennifer Agate is a managing associate and Erika Federis-Cox is a trainee solicitor at Foot Anstey