Art crime is a peculiar thing, existing somewhere between the ugly world of armed robbery and the gilded halls of the State Hermitage. In our line of work we have to greet both with equal grace.

A great deal of my experience is in the resolution of Nazi-era historic claims, and I’ve been involved in some of the most important, and indeed bizarre, in recent years. Take the Gurlitt case, for example. We spend half our lives correcting a common misconception in the world of art crime: that there is an elderly collector in an underwater lair surrounded by priceless missing masterpieces. But the discovery of the Gurlitt trove in Munich two years ago gave us all a healthy serving of humble pie. In our defence, there was no underwater lair, but the elderly collector and priceless masterpieces were all present and correct.

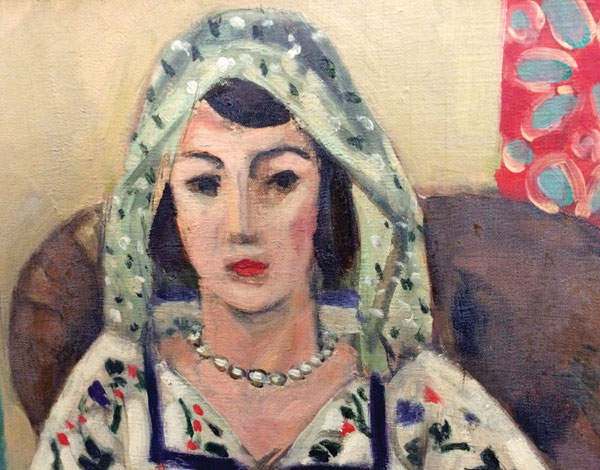

Among the 1,400 or so works that Cornelius Gurlitt stashed in his dingy Munich apartment was a stunning seated portrait of a young woman in a Romanian blouse (pictured), one of Henri Matisse’s finest. Gurlitt inherited the entire trove from his father, a dealer permitted to trade in ‘degenerate’ art during the Third Reich, and they kept him company for five decades. However, along with a number of other works in the hoard, the Matisse had been forcibly confiscated from a family before the war. So when the works were discovered in 2012 and the Matisse was among them, it was my job to get it back.

Involving initial conversations with and submissions to the German task force assigned to the case and then engaging with Gurlitt’s lawyer directly, I was charged with proving the work’s initial looting in 1941 and making the case for its rightful return. The former was simple enough thanks to our excellent network of provenance researchers around the world; the task force, presented with indisputable evidence of the looting, ratified the work’s status in June.

However, if you’ve kept up with the coverage around this case in the months since, you’ll know that the process has been an increasingly complicated one. Following Gurlitt’s death all his works were bequeathed to the Kunstmuseum Bern, a poisoned chalice if ever there was one. It took six months of analysis before the museum decided to accept it, excluding the looted works and promising their return to the families from whom they were taken.

But even now questions remain over the 400 or so ‘degenerate’ works in Gurlitt’s house and the task of establishing their clear title will likely be a momentous one. If we’ve learned anything from the Gurlitt case, it is that there is no such thing as an open and shut case for historic claims.

This year most of our work has been concerned with a particular corner of the market: cultural heritage. It’s a term that we often take for granted but recently, largely thanks to Amal Clooney’s crusade into Athens in October, cultural heritage has been a hot topic.

Along with leading barristers in the field of cultural patrimony, Mrs Clooney has renewed the discussion around Greece’s pursuit of the restitution of the Parthenon Marbles from the British Museum, where they were taken after Lord Elgin was allegedly granted permission to remove them from the Acropolis in Athens.

Many cases we take on at Art Recovery International require us to wrestle with this question of ‘ownership’, juggling the law of present day and the injustices inflicted in the past to settle a dispute.

Answering the questions of ownership in the Gurlitt case and many others from the Nazi period is as much a mitigation of risk as it is about righting historical wrongs. Though it is said that a provenance researcher’s work is never done, given the sporadic emergence of historical documentation, the greatest possible exploration of a work’s history is the first line of defence in establishing clear title for a work of art, large or small.

As such, we are committed to introducing the idea of ‘know your artwork’ to buyers, dealers and sellers, in much the same way as due diligence is standard practice prior to undertaking business with a new party. One need only look to the foreign news section of anewspaper to reveal the feeding frenzy befalling Syrian antiquities in the wake of recent instability.

In the future, works taken illegally from Syria and Iraq could be the next Parthenon or Gurlitt cases, with international media attention or world-renowned barristers knocking at the doors of those careless enough to deal in them. And this should be the most compelling point — injustice and wrongdoing have between them an incredibly long memory and, in an increasingly litigious society, due diligence in the art market is not just good practice but good sense.

Christopher A Marinello is the chairman and founder of Art Recovery International