About 300 watches with a total value of £4 million were swiped from people’s wrists in the West End of London between April and September 2022, many of them made by the kinds of brands whose handiwork appears in the pages of glossy magazines such as Spear’s. The trend has even started to affect international relations, with Indian entrepreneurs raising the issue recently during a meeting with shadow foreign secretary David Lammy.

[See also: Patek Philippe brings its Rare Handcrafts Exhibition to London]

So it was not before time that the Metropolitan Police mounted a sting operation that saw plain-clothed police officers sporting tempting watches and then arresting those who tried to swoop. Perhaps as a result, things seem to have moved in the right direction: watch robberies halved in the year to July 2023 across three of London’s wealthiest boroughs.

The haves and the have-nots

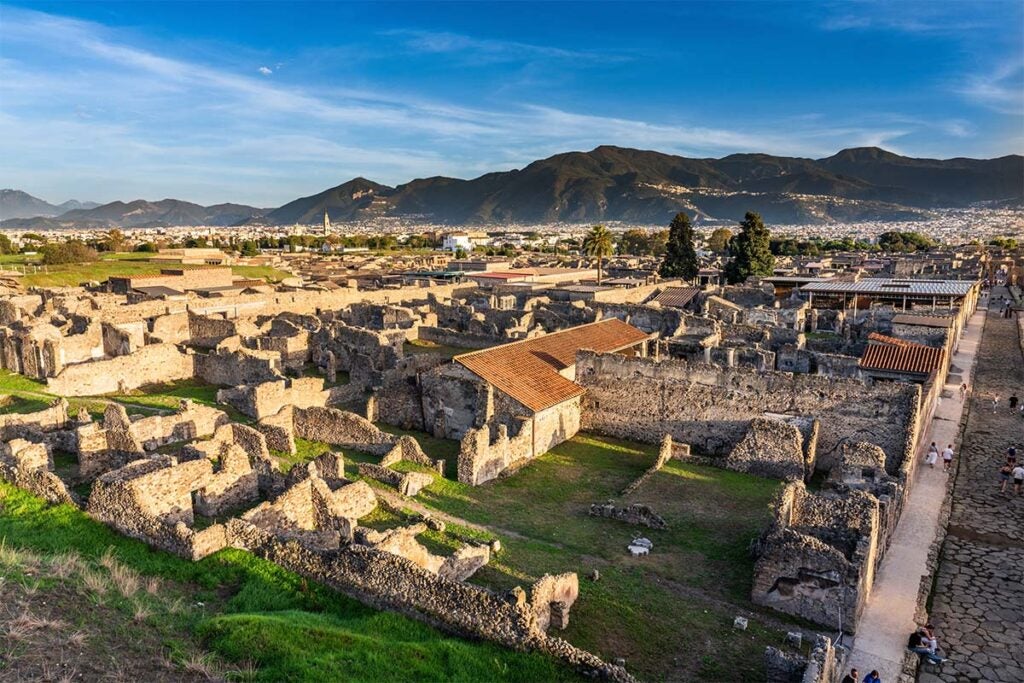

For me, the story brought to mind an ancient phenomenon: the sometimes uneasy cheek-by-jowl relationship between the haves and the have-nots in tightly packed cities. Indeed, in the same week that news emerged of the decline in watch thefts, an excavation in Pompeii brought to light an ancient complex in which rich and poor were found to have lived in uneasy proximity to one another.

The building was owned by a wealthy aspiring politician named Aulus Rustius Verus or one of his supporters. Buried beneath the thick debris that has covered Pompeii since the eruption of Vesuvius in AD 79 was an extraordinary high-ceilinged living room. The frescoes are still emerging but are as opulent as you might expect, with richly coloured scenes of columns and skies, and exquisite patterning.

The other side of the wall tells a different story. Here was a bakery – politicians often bought votes with gifts of bread – operated by slave labour. Indentations in the floor were used to coordinate the repetitious movements of slaves and blindfolded donkeys as they sought to grind grain with millstones. The windows were too high to see out of and were barred like a jail.

Faced with such evidence, it would be easy to suppose that social mobility was as challenging back then as it can be today, but Roman history is full of people who made the transition from one side of the divide to the other. It can be easy to forget, for example, that Julius Caesar lived in the Subura, one of the poorest districts of Rome, until his election as Pontifex Maximus in his mid-thirties. An earlier populist named Gaius Gracchus, by contrast, courted the plebs by proposing measures to improve their lot and relocating from the Palatine Hill, where the rich lived, to a less salubrious part of town.

[See also: How to master Christmas party small talk? Do as the Romans did]

In Late Republican Rome, too, we read of an aristocratic demagogue demoting himself in class to run for the political office of tribune of the plebs. But we also read of freedmen (former slaves) entering politics and amassing great wealth. The Dinner of Trimalchio, a satire I’ve mentioned before in this column, centres on the tasteless extravagance of a fictional former slave.

Did the partial segregation of rich and poor, freeman and slave, help or hinder change and progress? It is difficult to imagine the slaves who ran the Pompeian bakery viewing their proximity to a luxurious villa as anything other than a reminder of social injustice. And yet, the prospect of manumission (freedom) was routinely proffered to slaves as an incentive to good behaviour, and some did, as freedmen, come to own luxurious properties of their own. The House of the Vettii in Pompeii, for example, belonged to two ex-slave brothers who became wealthy traders. The villa’s remarkable décor is likely to have been inspired by those of properties the brothers had peered into in the past.

Perhaps it is the seeming impossibility – for many – of making a Vettii-like transition that has led to spikes in the theft of luxury items. As for going from riches to penury, politicians who seek to underplay their wealth and privilege should be mindful of the extremes to which their ancient forebears went to appear to be men of the people. For that matter, when did you last see Rishi Sunak wearing a watch?

This column was originally published in Spear’s magazine: Issue 91. Click here to subscribe