How do you bring what marketing men like to call — and I type it with a wince — ‘added value’ to Shakespeare? It’s an odd question, given that the texts themselves can be pretty fairly held to have quite as much value as any collection of 900,000-odd words in the language could hope for. And yet it’s a question that admits of answers. The first and most obvious one is that you perform the plays.

But for the reader there is another — and it is one that has been magnificently addressed by the Folio Society to celebrate the 450th anniversary of the Stratford man’s birthday this spring.

You can edit them well, set the text beautifully, add such scholarly paraphernalia as is necessary to enlarge the ordinary reader’s understanding… and then make them into beautiful objects. People have been taking this step for hundreds of years. But the completion of the Letterpress Shakespeare Project, republishing all the plays and poems in super-posh hand-bound, hand-marbled, hand-printed individual editions, takes things a bit further.

It’s not a scholarly edition (though — as the warnings on the sides of biscuit packets put it with regard to nuts — it has been made in a factory that also handles scholarship). It’s a reader’s edition. A very wealthy reader, it might be added, with copious shelf-space and (perhaps) a slight streak of vulgar ostentation.

To tell the story by numbers, the project has taken eight years. Each play represents eight hours of work a day for six weeks. The comedies are in green, the tragedies in blue and the history plays in red, with the sonnets and poems bound in a single, turquoise volume. They are a limited edition: only 300 copies of each book (that’s guaranteed: the type has already been melted down). The plays are £295 a pop and the poems £345. The whole lot in one go will set you back £11,555.

Naughty but niche

Anyway, the existence of this remarkable beast seems to bear out one of the sensible predictions that has been made about the future of books (or ‘Future Of Books’, as one imagines the portentous capitalisation in those endless discussions and symposia). That is, the smart money has predicted a vanishing middle-ground: the ease, cheapness and portability of digital editions will eclipse paperback and some hardback sales.

The paperback’s selling point as a technology is that it was, as Allen Lane brilliantly recognised when he launched Penguins on to the world, the easiest and cheapest and most portable delivery mechanism for text. Now it is not.

But that doesn’t mean that dead-tree books will disappear. Rather, it’s plausibly suggested, the digital age will throw extra attention on book-as-object rather than book-as-delivery-mechanism: we’ll see the physical book, where its materiality is to the fore, as heirloom, as art object, as fetish. Here is this prediction lavishly embodied. At one end of the continuum are the limitless (and searchable) bounties of the free Shakespeare app on my smartphone. At the other end is… this.

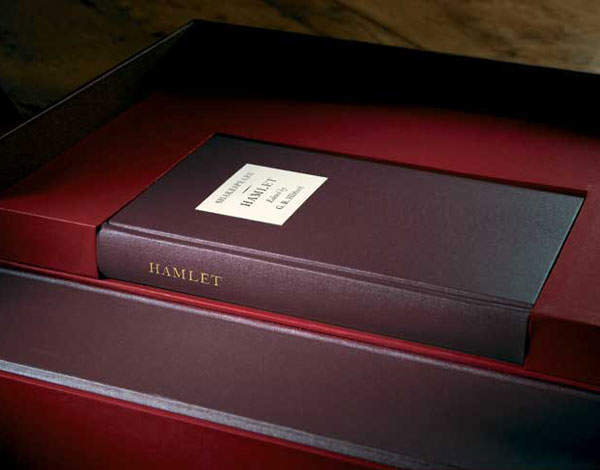

Gimme, gimme, gimme. I borrowed a copy of The Tempest, there seeming a pleasing torque in seeing so substantial an edition of a play that deals in the insubstantial. When the courier arrived he was bearing a package roughly the size and weight of an occasional table. Thick layers of outer cardboard removed, I picked open an inner package wrapped tightly in brown paper. Inside was a solander box (like a big hinged slipcase) in dark green buckram a shade bigger in each direction, I’d say, than a volume of the Shorter Oxford Dictionary.

Nesting inside that was the play itself: about fourteen inches by eleven, hand-marbled, half-bound in goatskin and titled in gold leaf. The pages inside — just 80 of them, thick, deckle-edged, mould-made paper — contain nothing but a clean text of the play, hand-printed in Baskerville the old-fashioned way. The glossaries, introduction, notes on the text, footnotes and so forth — the edition is Stephen Orgel’s 1987 Clarendon Press one — are confined to a separate hardback volume hiding in the solander box under a false floor.

You need to sit in a chair to read this. But, ah, it’s a pleasure to do so (once you’ve ensured the chair is clean, your hands are clean, your lap does not have any of your breakfast egg on it and your coffee is safely in the next room). The text doesn’t half breathe — especially if most of your Shakespeare-reading life has been confined to paperback Ardens or a scragged old copy of Collins’s single-volume Alexander Text.

This is Shakespeare bling — I think the word’s appropriate, though it might not be the one the Folio Society would choose — at a very high level. All that glisters, and so on, but still. If I had a spare twelve grand and — frowns at calculator — nine feet of shelf-space… y’know, I’d be seriously tempted.