The investor and social scientist Charlie Munger, who died in November at the age of 99, had the rare skill of paring topics back to their essentials. For him, the secret sauce was nothing more than investing thoughtfully and only trading infrequently. ‘The wise ones bet heavily when the work offers them that opportunity’, he used to say. ‘The rest of the time they don’t. It’s just that simple.’

Determining when the conditions are right to ‘bet heavily’ is not as easy as it sounds. At present, many in the family office community do not feel that the environment is right for dialling up risk in portfolios. In fact, it feels more like a moment to rein back or at least hold off on doing anything too risky. I sounded out the family office community, and for many it is a question that they and their investment committees are posing, particularly when looking at illiquid investments such as private equity.

[From the magazine: How the rich and famous fell for Miami]

Dalma Global CIO Gary Dugan specialises in advising family offices. He says: ‘Generally speaking, the best time to increase risk is when you are confident in your investment view and volatility is relatively low.’ However, many of the family office CIOs I’ve spoken with recently privately admit that they are not feeling confident in their views, preferring to sit on the proverbial investment fence. When asked about capital deployment plans into illiquid investments, many stated that they had paused these completely, particularly for funds destined for real estate or private equity.

One family office CEO summarised her thoughts in the following way: ‘There just isn’t enough realism in valuations yet for us to get comfortable. We would rather miss out on opportunities than catch a falling knife.’ This reluctance to tie up funds seems to be confirmed by the latest Citigroup family office report, which highlighted a significant change in sentiment towards private markets, with only 32 per cent of respondents bullish on private equity compared with 49 per cent the previous year.

Maurizio Arrigo of Pictet does not see the same caution spilling over into private investors more broadly. He told Private Equity International that his clients’ interest in private equity has not decreased. Nevertheless, institutional investors are not just pausing but are also making significant cuts to their private equity allocation. Data published by Hamilton Lane suggests that, when the final numbers are in, 2023 will be on a par for fundraising with 2022 – so not a disastrous year, but substantially lower than the record fundraising year of 2021.

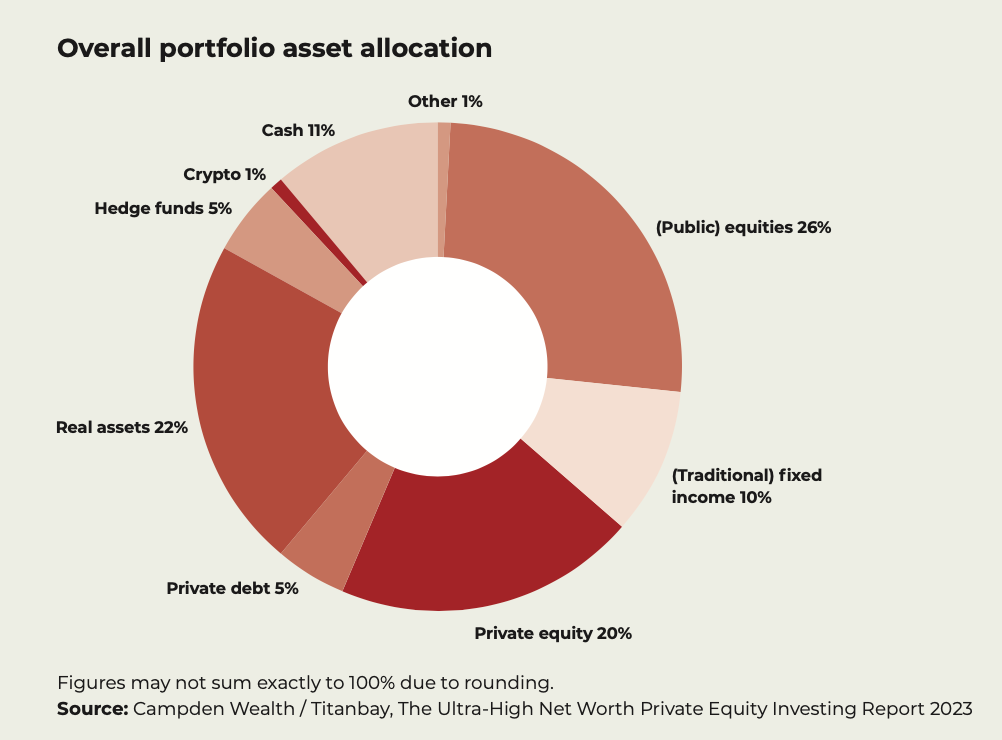

I have observed that some family office CEOs are questioning not just the timing of their next capital deployment, but also the long-term role of PE in their asset allocations. There is increasing scepticism about the ability to select and access the funds that will reward investors for the illiquidity and the additional risk of investing in PE.

[From the magazine: Introducing Spear’s Magazine: Issue 90]

On the face of it, the much-vaunted illiquidity premium does seem to exist. Hamilton Lane industry data shows annualised returns of 16 per cent for private equity compared to 12.9 per cent for the S&P 500 over the 10 years to 30 June 2023. However, the difference between the top quartile and the bottom quartile buyout fund averages 13.7 per cent per annum over the past 15 years, and access to the top quartile is notoriously difficult.

The outstanding historic performance of the super-endowments such as Harvard and Yale encouraged many endowments and family offices to try their luck and attempt to replicate this success by increasing their exposure to illiquid assets such as private equity. But in a 2020 article, Dennis Hammond found that the average endowment was not only unable to mimic the returns of the super endowments but that it also underperformed a traditional 60/40 mix both on an absolute and risk-adjusted basis over the 46-year period for which data is available. As Guy Hands of Terra Firma once put it: ‘We buy stuff with cheap debt and arbitrage on the difference with equity markets.’ Given the current lack of cheap debt and the difficulties associated with accessing top-quartile private markets funds, it’s unsurprising that some family offices are re-evaluating.

[From the magazine: Populism is on the march – again]

I don’t think this negates the case for private equity, but it’s wise to ask whether a given investment would still stack up without leverage. Excess returns generated primarily by cheap leverage will prove elusive in the new interest-rate environment.

I will finish where I started, with further pearls of wisdom from the late, great Charlie Munger and his partner Warren Buffett at the Berkshire Hathaway 2019 AGM: ‘We have seen some more high-IQ people – really extraordinarily high-IQ people – destroyed by leverage.’ When this happens, the fairytale turns to ‘pumpkins and mice’.

Annamaria Koerling is managing partner of Delfin Private Office

This feature first appeared in Spear’s Magazine: Issue 90. Click here to subscribe