Some of the selections here might have the effect, as well as whiling away the hours, of making us count what remains of our blessings

I found myself writing, not long before things went to hell in a plague-ridden handcart, that when it comes to apocalyptic black swan events such as the one we’re going through now, the writers of speculative fiction tend to imagine them better than insurance actuaries. I stand by that.

Accordingly, it seems to me it’s worth spending some space here looking at fictional treatments of the sorts of thing we’re experiencing. I don’t do so to be flippant or in bad taste: I really do believe that literature helps us make sense of human experience, and that that applies to the extreme as well as to the commonplace.

By reading the literature of plagues and devastation, you open your imagination to the wise things that have been said about these experiences; and perhaps, in reading the more lurid and pulpy of them, you can take comfort in imagining how much worse it could have been.

It also bears saying that all these books are classics of deserved reputation and high literary value – with the possible exception of Dean Koontz.

You can’t go wrong reading them; and if you’re going to read them, when better than now? The towering twin monuments of the literature of plague, of course, are Boccaccio’s Decameron and Daniel Defoe’s Journal of the Plague Year.

In both of them – one relating to an outbreak of the Black Death in Florence in 1348; the other one in London in 1665 – you can see the same things happening as we see now, a welcome assertion of common humanity even as it offers evidence that we don’t learn much from our mistakes.

There was the mass communication – as Boccaccio put it: ‘The violence of this disease was such that the sick communicated it to the healthy who came near them, just as a fire catches anything dry or oily near it.’

There was a mixture of responses from panic to denial. In Defoe’s description, for instance, I think of those idiot kids pouring into Miami on Spring Break: ‘They did not take the least care or make any scruple of infecting others.’ There was – then as now – flight from cities, looting and disorder, the proliferation of conspiracy theories, and the piling-up of the unburied dead.

Then there’s Camus’s La Peste, which tells us what happens when existentialists get cooties – cholera, in this case. This may help those of us stricken in one way or another to wrangle with the question of whether suffering has meaning, whether fate has a sense of humour, or whether all this is just rotten luck for the species.

As far as the practicalities of post-apocalyptic life go, I also recommend Richard Matheson’s outstanding I Am Legend (in which vampires have made the world barely habitable), John Wyndham’s Day of the Triffids (comet; bad-tempered plants), Kurt Vonnegut’s Cat’s Cradle (room-temperature ice), JG Ballard’s The Drowned World (room-temperature water), Russell Hoban’s Riddley Walker (nuclear holocaust) and Cormac McCarthy’s super-grim The Road (nuclear holocaust, probably).

At the hysterical end of the market – offering imaginary diseases that are both more contagious and more deadly than Covid-19 – are Stephen King’s The Stand and Dean Koontz’s Eyes of Darkness. (The latter’s plague is, spookily, called Wuhan-400, which has earned Koontz a certain amount of attention recently from conspiracy-prone types on the internet).

Think of these, perhaps, as diverting but also – in their extremity – consoling fantasies.

Things are bad, but they aren’t The Stand, and they aren’t likely to get there. Finally, may I also recommend Richard Preston’s The Hot Zone, a nonfiction story as gripping as a novel that tells the true story of the time ebola escaped into the wild from laboratory monkeys in a suburb of Washington DC in 1989.

It’s the story of a near-miss – it turned out that this form of ebola, which (heaven help us) was airborne, didn’t turn out to be communicable to human beings – but it is quite the reminder of how vulnerable we are, and always have been, to the chance mutations of nasty bugs.

At least some of these might have the effect, as well as whiling away the hours, of making us count what remain of our blessings. Stay safe, folks, and stay indoors.

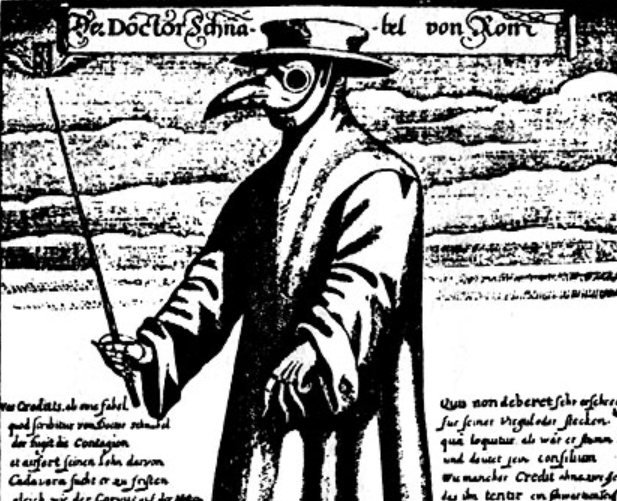

Image: Doktor Schnabel von Rom (“Doctor Beak from Rome”), engraving, Rome 1656

This article was published in issue 74 of Spear’s magazine. Click here to buy and subscribe

Read more

Summer reading: Three of the best books out now

Books: A ‘pithy’ guide to history’s most influential economists

Dame Steve Shirley CH on Zoom, philanthropy and her upcoming biopic