Rishi Sunak’s rain-soaked surprise announcement that the UK General Election would be held on 4 July certainly surprised the media and has now fired the starting gun on a five-week election campaign. The economy will, I am sure, feature prominently in the campaign and will be the source of much debate and argument between the leading parties.

In anticipation of the truth being the first casualty in this battle, I thought I should highlight again some interesting and pertinent facts about the UK economy that will likely get drowned out in this upcoming war of words. This is not an attempt to be party-political. It is designed to inform and act as a counter-narrative to the onslaught of depressing commentary we are assailed with daily about how awful everything is in the UK.

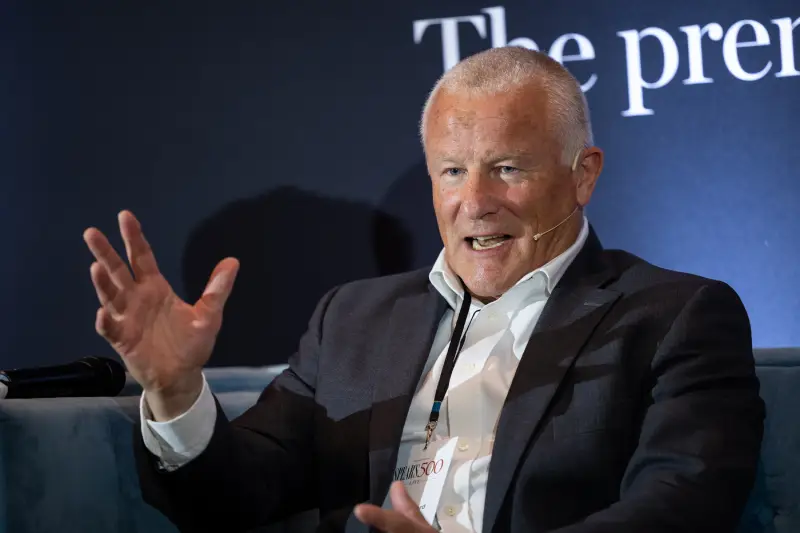

[See also: Neil Woodford: UK equities poised to rally after 20 years of underperformance]

Is the UK in decline? Where’s the evidence?

I recently witnessed more of this depressing narrative in person. Two speakers I listened to at a conference I attended in London commented that the UK ‘was undoubtedly in decline’, but as is often the case, neither cited any data or facts to back up this increasingly consensual perspective. If I had had an opportunity to question these two speakers, I would have asked what data they were relying on to support this perspective, and maybe if this was the standard all commentators were required to meet, we might get a more balanced debate about the health of the UK economy. In the meantime, you can hold me to account because I will back up my assertions with data so that you can see exactly what I am relying on to support what I am saying.

So, is it ‘all over for Blighty’, as someone also asked me this week? Joking apart, I hope to show you that far from being all over, the UK economy is in relatively robust health and is poised to deliver growth ahead of a still very downbeat consensus.

[See also: Why ‘yes, but’ is the story behind our economic outlook]

Before presenting the evidence supporting my perspective, I should also say that I am not advocating unquestioning optimism. Many intractable problems confront the UK economy, none of which have easy solutions. For example, the challenges in the free at-the-point-of-entry health system as it grapples with an ageing population and an obesity crisis, a public sector struggling with declining productivity, the requirement to deliver growth alongside net zero emissions, the need to reverse decades of environmental degradation and an economy overburdened with excessive regulation. However, these problems are not unique to the UK economy. These are challenges all economies have to confront, and all will require bold political leadership and, most importantly, new technology if enduring solutions are to be found and implemented. If I am an optimist in any sense, I believe in human ingenuity to continue to overcome these and the many other challenges confronting humanity.

So, back to the UK economy. Just as a doctor might look at a range of key parameters to judge a patient’s overall health, there are several key economic indicators that point to the overall health of an economy. I hope to show you here that by reference to some of those indicators, the UK economy is faring well and doing far better than the terminal diagnoses of the commentators that represent a crowded consensus. Importantly, I am not claiming that the UK economy is the equivalent of an Olympic athlete, but in comparison to its peers, it is performing well and is likely to see an improvement in that relative performance in the months ahead.

Inflation

Let’s start with inflation, which has been a considerable headwind for the economy since the end of the pandemic and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022. For reasons that have nothing to do with domestic interest rates, inflation has now fallen as rapidly as it rose and is now back nearly to the Bank of England’s 2 per cent target. This is good news in the first instance for the government because its finances are hit hard by higher inflation (index-linked debt interest payments, index-linked benefits and pensions) and for consumers whose real wages fell after the initial surge in inflation and who also had to confront a non-discretionary energy price tax in the initial aftermath of the war.

As an aside, UK inflation is now more than 1 per cent below that in the US.

Appropriately, in my view, the government stepped in, at considerable expense, to insulate businesses and consumers from the worst effects of this crisis by introducing the energy price guarantee scheme. Now, energy costs, as measured by reference to the percentage of post-tax earnings, are back to where they were at the start of the pandemic.

This precipitous fall in inflation is excellent news for the economy, both public and private sector. Next, I want to focus on what this collapse in inflation means for real wages.

Consumers- income and balance sheet

In nominal terms, after a spike in settlements in 2022 and 2023, in response to the surge in inflation, wage growth in both the private and public sectors has now settled at about 6 per cent (see below)

But in real terms, following the fall in inflation, this now translates into robust real wage growth that will likely exceed 4 per cent in 2024.

A key unknown as we look through the remainder of this year and into next is what proportion of this growing income will be spent and what proportion will be saved. The Bank of England, for example, to make sense of its gloomy expectations for economic growth, has the saving ratio which is already well above the average of the last ten years, rising further to 11 per cent. My guess is that this higher saving is unlikely, given the already very robust nature of the aggregate consumer balance sheet (see below) My view is that this robust growth in real incomes will support strong growth in consumer spending, which will drive overall economic growth well beyond the consensus expectation.

(By way of comparison, household saving in the US is at 3.2 per cent. In a parallel universe where the UK consumer had shifted to a saving ratio similar to that of the US, we would have seen UK economic growth exceed that seen in recent years in the US. It is an interesting thought experiment and one in which I suspect doom-laden commentary would have been less predominant).

The news is even better on a post-tax basis and for someone with average earnings. As a result of the significant reductions in National Insurance in 2024, real post-tax average earnings in 2024 will see the strongest growth in over 20 years (see below).

Employment

If those in work are seeing good growth in real incomes, what about the number of people in work, and what about a longer-term perspective on the labour market? Here is a chart showing the number of people employed in the UK since December 2018.

For a longer-term perspective, here is a chart (below) of UK unemployment from March 1971 through March 2024. If you knew nothing else about the UK economy, this alone would be hard to reconcile with the ‘UK economy undoubtedly in decline’ narrative. As an aside, I am old enough to remember what life was like in the 1970s. That really did feel like decline and, in my opinion, is a million miles away from where the UK economy is today.

For those of you with an appetite for data (I promised to back up assertions with facts), the table below gives a pretty comprehensive picture of what has happened to the labour market in the UK over the last 24 years. Please draw your own conclusions, but, for what it’s worth, mine are that these data are just not consistent with the economic decline narrative. Indeed, quite the opposite.

Corporate sector

I have tended to focus on the consumer sector in this analysis, principally because it is the economy’s largest and most influential sector. However, the corporate sector is also vital to the health of the UK economy. A detailed analysis of its health and prospects is a giant subject worthy of pages of analysis, but if I were to focus on just one metric as a proxy for the level of confidence businesses in aggregate had in the UK economy’s prospects, I would focus on the level of investment spending.

If businesses, in aggregate, thought that the UK was in some sort of secular decline, this would be reflected in low levels of investment spending here in the UK. By implication, those same businesses would presumably prefer to invest abroad, which would show up in the national accounts as capital exports.

The data shows that the UK economy doesn’t confront this problem. Indeed, as you can see in the chart below, investment spending as a share of GDP is close to a 26-year high.

While we are on corporate Britain, I should also mention the banking system’s health. Not so long ago, back in 2008, when the UK economy confronted an existential crisis in the form of a failing banking system, which required radical and coordinated central bank action to solve, UK banks had bloated balance sheets (too many loans) and ridiculously low levels of loss-absorbing capital. Interestingly, I don’t recall the consensus narrative being downbeat on the UK before this crisis hit. Indeed, quite the opposite.

Despite a very close call, the banking system survived and is today totally transformed. Deposits in the UK banking system are now substantially bigger than loans (see below), and banks have more loss-absorbing capital than they have ever had. As an aside, they are also now delivering very attractive returns on that capital, which is again indicative of a healthy corporate environment here in the UK—again, something which the gloomy consensus pays little attention to.

I included the following two charts to add more colour to this section. Both speak for themselves and give a clear perspective on how different the period after the financial crisis is from that which preceded it.

Public finances

If there was one subject the detractors of the UK economy would likely choose to focus on, it would be this. In common with every other developed economy, debt to GDP in the UK has increased significantly in recent years. This increase is largely the product of the government’s choices during the pandemic and the energy price crisis to insulate the economy from the worst effects of those global events. These were expensive interventions, but importantly, not in my opinion, the product of systemic fiscal incontinence. Here is a summary of the costs of all the extraordinary measures deployed during those two crises.

These exceptional measures totalled just over £240bn. Viewed from a longer-term historical perspective, the current level of public debt, with the UK having just fought a 21st-century equivalent of a war, doesn’t look as alarming as many claim, and neither does its affordability as measured by debt interest payments as a proportion of tax receipts.

I am not suggesting public debt isn’t high, and I agree that borrowing needs to come down, but with inflation now back at the MPC’s target and with the deficit falling significantly over the next few years (see below), the situation is nowhere near as alarming as many have suggested. Indeed, the deficit reduction shown in the second chart below is based on the OBR’s very gloomy growth forecasts. These already look significantly too low following Q1’s 0.6 per cent growth. My guess is that as growth forecasts inevitably rise in the months ahead, the deficit reduction timescale will improve commensurately.

My conclusion regarding the UK’s public finances is that the alarmist rhetoric is misplaced. Debt is too high, as is its cost, but when viewed in the context of history, it is far from extreme. With tax receipts likely to keep improving, reflecting better economic growth and debt interest costs falling in line with the steep decline in inflation, the underlying trends are moving in the right direction.

Productivity

This is another favourite topic for those inclined to be downbeat about the outlook for the UK economy. Economic theory suggests that economic growth is ultimately driven by the number of people in work and the growth in their productivity (Output per worker).

Many economists highlight that the UK economy underperforms on this metric, and it is true that in relation to our near European peers, who have had structurally higher unemployment than the UK, the quid pro quo has been that those economies have had higher productivity. Ultimately, there is a choice here. For those who criticise the UK for its relatively low productivity, would you be happier then if the UK was more productive but with fewer people in work? This trade, like many others in economics, has no easy answers.

[See also: HNWs bullish on future of UK economy, report finds]

For many complex reasons, the UK economy has solved this conundrum by having lower unemployment and lower productivity in aggregate than our European peers.

Going forward, if the UK economy is to sustain the better growth rate it will see this year and in 2025, it will have to become more productive while also maintaining levels of employment. On this front, the signs are encouraging in the private sector, given the high levels of business investment the economy is witnessing. Ultimately, workers become more productive if they combine their skills with better technology. This incentive, manifest in higher returns on invested capital, drives companies to become more productive. The same should also apply in the public sector, but the incentives can be less direct for all sorts of obvious reasons.

Another thing that would liberate productivity in the UK economy is deregulation. My own experiences of many industries suggest that many are overburdened with unnecessary regulations that may have originally been well-intentioned but ultimately benefit no one. It is no coincidence that the least regulated economies globally have the best growth records. Importantly, I am not advocating a free-for-all. Appropriate regulation is a force for good. Excessive regulation stifles an economy and ultimately leads to worse outcomes for all.

Conclusions

This ended up being longer than I originally anticipated. It is not designed to make any political points but is intended to offer an evidenced-based perspective that runs counter to the widely held view that the UK economy is in some sort of terminal decline. There are many areas for improvement, but in both absolute and relative terms, the UK economy is in a good place and will see growth in 2024 and 2025 significantly exceed a pessimistic consensus.

Here is a summary list of the things I have relied on to make these points:

- Inflation is now back at the MPC’s target and is currently significantly below inflation in the US economy.

- UK consumers, in aggregate, are in rude financial health. They have substantial net deposits and are enjoying the strongest post-tax real earnings growth in over two decades (People on average earnings).

- Unemployment is close to a 50-year low.

- The UK corporate sector appears to have confidence in the economy’s outlook, given that investment spending as a share of GDP is near a 26-year high.

- The banking system is robust and healthy, with substantial loss-absorbing capital.

- Public finances are stressed after two exceptional and expensive crises. The deficit is now declining, and debt to GDP is peaking. Both metrics will improve significantly as the economy grows ahead of consensus expectations over the next two years.

- Productivity in the UK is lower than in many of our peer economies, but unemployment is also lower. Going forward, I expect this metric to improve and not at the expense of those in work.

In the medium term, policymakers could and should do things to improve the economy’s ability to sustain this period of growth. Whether they will have the foresight and political bravery to do so, we will have to see, but in the meantime, the economy’s continued outperformance will give whoever ends up in government the room at least to think about these issues.

Neil Woodford blogs about economics at woodfordviews.com